Records Show Omaha Police Surveilled BLM Organizers, Including a Legal Aid Clinic and Birthday Party

BY Emily Chen-Newton

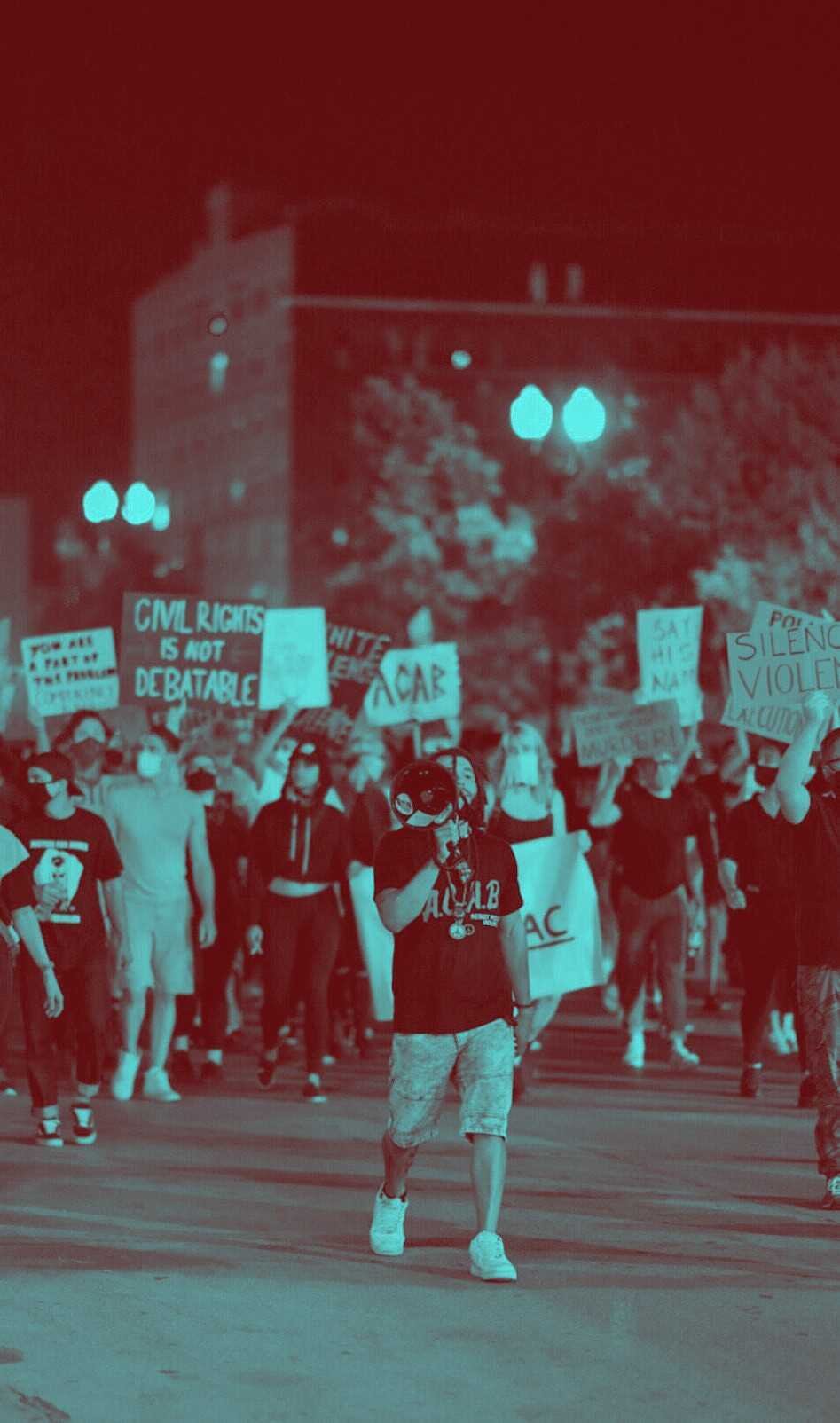

Emails revealed through a records request by the ACLU of Nebraska show the Omaha Police Department used Facebook, bodycams, and at least one fake social media account to surveil Black and Brown activists during the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020. These records are considered public and have now all been released to the media by the ACLU of Nebraska.

Following the protests last May ignited by the police killing of George Floyd, Nebraska’s ACLU filed a records request with the Omaha Police Department (OPD) regarding the department’s use-of-force against protestors. The resulting records revealed what the ACLU’s Executive Director Danielle Conrad characterizes as, “deeply troubling” email communication.

An email thread including Omaha Police Chief Todd Schmaderer and the mayor’s office referenced by name a private citizen with no history of criminal conviction who was organizing bail support for protestors- a legal activity. Later emails show officials* communicating with OPD about the suspected whereabouts of this organizer, Morgann Freeman, who became well known throughout the summer for organizing and crowd-funding supplies for protests. This discovery prompted the ACLU to submit a subsequent records request to both the mayor's office and the Omaha Police Department seeking documents pertaining to certain prominent local organizers. The return of this request revealed hundreds of email communications tracking legal and First Amendment protected activities of primarily Black and Brown organizers in Omaha.

NOISE obtained copies of the records and spoke with several of those whose names popped up in the subject lines and content of police emails. Local organizer, Ja Keen Fox, was surveilled to the extent that emails were sent between officers about his birthday party, including the location. Fox told NOISE that knowing how activists are followed by law enforcement nationwide, he wasn't surprised when it happened to him. But, he added, “as a human being you understand that there is a mental and psychic toll…knowing that you are a target in the eyes of people meant to protect you.”

While many of the activists believe they were on the radar of the police for years before 2020, the increased surveillance seems to coincide with OPD’s implementation of an Alpha/Bravo shift structure (officers working 12-hour shifts every day) in response to the racial justice protests. When speaking to the Omaha World Herald in July of 2020, Deputy Chief Michele Bang said, “If you were working, you were helping (with the protests) in some form.” It was reported by multiple news outlets last year that the Omaha Police Department paid out $2.5 million dollars in overtime during the 10-day span of the department’s Alpha/Bravo shifts. And OPD’s Lieutenant Sherie Thomas confirmed to NOISE that for officers “assigned to the Intelligence Unit” monitoring social media was within the scope of their work.

NOISE reached out to the Omaha Police Department for an interview, and while the interview was declined, several of our questions were answered by Lieutenant Sherie Thomas over email on behalf of the department. She noted OPD consulted the city’s legal department regarding the sources of intelligence they could legally access, and “many times organizers would not meet with the OPD in order to pre-plan for a safe event, therefore the only way we would have known about a large-scale event was from social media.”

None of the emails released to the ACLU show events planned by the surveilled activists called for violence and most were activities protected by the First Amendment.

Events included:

a memorial walk for Zachary Bear Heels, a Lakota man killed by Omaha officers in 2017

a prayer vigil for James Scurlock, a Black protestor, killed by a white bar owner during the 2020 protests

a legal clinic hosted by the ACLU (at Culxr House) after the arrest of nearly 130 protestors.

a former NOISE reporter’s livestream of a city council meeting

various marches and rallies, including one at the Malcolm X Memorial Foundation

a Black Lives Matter street painting event (planned but canceled)

a sidewalk chalking event

“The Omaha Police Department wasted taxpayer money following me because I stood up for the people, against racism, oppression, and brutality. I hope it was worth it,”

-Senator McKinney

Despite the nonviolent nature of these events, orders were sent via email to monitor and prepare varying levels of force. In response to the ACLU’s planned legal clinic for example, Captain Mark Matuza requested the event be monitored by a car nearby to “provide visual.” For the Zachary Bear Heels memorial walk, command was given that, “Officers shall not take a knee,” and an arrest van was readied with officer assigned duties including “PEPPERBALL & TANK.” And “over 100 National Guard” were staged near the Malcolm X Foundation for a rally according to an email from Captain Matuza.

While tracking a speaking event planned in North Omaha, an officer noted “looks to not be so much of a rally or protest.” But Captain Matuza wrote, in case “this could go sideways, plan on having RDF and SWAT called out.” The event featured prominent Black leaders such as Ja Keen Fox and Terrell McKinney who was running for a seat in the legislature. In a later email sent from Sargent Eric Schlapia, a note is made that McKinney “testified at the hearing for LB 1222, regarding police oversite,”(sic) but concludes “I don't find him threatening at this time.” McKinney’s predecessor, Ernie Chambers, who represented the historically Black District 11 before him, was closely watched by OPD during the civil rights era and like McKinney, is Black.

Not only was information about these organizers and events filling email inboxes within the police department, it was also being shared with those outside of the department. On at least one occasion information was shared with intelligence specialist Ed Oslica. Oslica has a focus in antiterrorism and intelligence analysis working with the United States Attorney’s Office for the District of Nebraska. In the same email thread, Oslica requests that U.S. Marshal Will Iverson be added to the email list, “sure, no problem” Omaha Police Officer Constance Garro replies.

Many of the activists said at some point over the summer they were concerned for their safety, as they noticed an increased police presence not just on their social media accounts, but also around themselves or their homes. And one organizer who spoke to NOISE, but asked to remain anonymous, expressed uneasiness for younger activists coming into the work, not fully comprehending the extent to which law enforcement is willing to surveil Black organizers. Alexander Mathews, who goes by “Bear Alexander” said he knows that being watched is part of being an activist.

“If I’m not being pressured and harassed by the government, by local law enforcement, then I, myself, as an organizer, am not putting enough pressure on said government.”

-Bear Alexander, an Omaha activist

One of the individuals most heavily watched by OPD eventually used a private security service last year, and both Alexander and Fox still say they expect to be harassed because of their activism. Alexander references the assassination of Black Panther Fred Hampton in Chicago after years of FBI and police surveillance, but while he’s aware of the history, he said he doesn’t fear for his own life, because, “I don’t think I’ve made any amount of significant traction to pose that kind of a threat.

The Omaha Police Department emails show officers, chiefs, captains, lieutenants, and members of the Narcotics/Intelligence Squad closely following individual organizers on social media, and using a fake account on at least one occasion to get more detailed information. An email sent from Lieutenant Trevor O’Brien reads, “Ofc. Galloway has been able to connect (under fake account) with Morgann Freeman,” regarding a nonviolent street painting event that was later canceled. This came after several department emails acknowledging that protestors knew OPD was using social media for intelligence. One email shared with the police chief and at least ten others explains they are seeing, “discussion talks about police monitoring social media and some groups are going private...We are attempting to enter the private chats.”

Fake accounts on Facebook and Twitter are against the platform’s rules, but in most U.S. states using them or other avenues on social media for intelligence, is not illegal. There are a few exceptions to this, such as the city of Memphis where a consent decree bars the city’s police from using social media to monitor activists. But there are no such regulations in Nebraska, and no legal action from the state’s ACLU is planned at this time.

Though the tactics may not be illegal, scholars of national security such as those at the Brennan Center for Justice have pointed out recently these kinds of infiltration efforts can have an even greater cost than the taxpayer dollars to which Sen. McKinney alluded. Mark Carter, staff attorney for the national ACLU says the “mind-boggling amount of resources'' spent surveilling Black activists, “is in stark contrast” to the resources spent tracking, “the far-right militias/white supremacist organizations, that there is plenty of evidence that they have organized to commit criminal activity...to commit violence.” Indeed, according to the 2020 U.S. Homeland Security Threat Assessment Report, white supremacist extremists (WSEs) remain the most persistent and lethal threat in America.

While OPD was closely monitoring prayer vigils, street painting, and speaking events hosted by Black activists last summer, a deadly act was perpetrated by a white man with an alleged history of racist behavior at his place of business and on social media. Seeking justice for 22-year-old James Scurlock became a rallying cry for many of last summer’s demonstrations in Omaha.

Local artists painted murals honoring James Scurlock on the plywood boarding up some of Omaha’s downtown businesses last summer.

Ja Keen Fox led an effort to occupy the sidewalk outside County Attorney Don Kleine’s gated community after Kleine said Jake Gardner shot Scurlock in self-defense and did not press charges. Fox organized with Culxr House to collect supplies and host volunteer training. Fox served on the mayor’s LGBTQ+ advisory board, before being forcibly removed last year for a highly publicized tweet that Mayor Jean Stothert said condoned violence. But while in the thick of those demonstrations, in a July 2020 interview with NOISE, Fox said much of his work is helping to educate people on how to protest safely and engage their First Amendment rights.

If you showed up to protest with Fox outside of the West Omaha subdivision, you were offered snacks, Gatorade, and a small pamphlet of protester’s rights. He told reporters then, and reiterated when interviewed for this story, that he was offering a safer alternative for people to participate in civil disobedience. By staging peaceful, and socially distanced protests in one of Omaha’s suburban neighborhoods, Fox felt he was giving opportunities for engagement with a “lower barrier of entry” for those getting involved in civil disobedience for the first time. “People were getting really hurt downtown,” he adds, so he was providing a safer alternative. Fox estimates about 1,000 people joined in the protests he organized outside of Don Kleine’s neighborhood. He suspects bringing more people into activism might have been what OPD perceived as the greatest threat coming from him.

“They aren’t afraid of us being violent, they’re afraid of losing their place in the system of power,” said Fox.

Mark Vondrasek is one of the only white organizers to be closely monitored by OPD according to the released emails, which he believes is due at least in part to his political stance. Vondrasek is unapologetically communist. There are other white activists in Omaha, Vondrasek says, but he also ran for office in both 2018 and 2019, “And being very public like that, in a very civic-minded, like, ‘let's talk about the problems’ kind of a way,” he thinks made him a target.

At least one email indicates that just being Facebook friends with Vondrasek was noteworthy in the eyes of some OPD officers over the summer. The email sent from Officer Constance Garro to Officer Thomas McCaslin points out that a particular account has both Mark Vondrasek and Kara Eastman as friends. Eastman lost a Nebraska congressional district race last year after months of attack ads from incumbent Don Bacon calling her a “radical socialist”.

“That's what the chalk was all about...just a very easy way to be like, you thought this was your space? It’s actually our space,” said Vondrasek.

But the majority of department emails about Vondrasek are about a sidewalk chalk event where he invited people to express their First Amendment Rights in water-soluble chalk on the sidewalk surrounding the police department headquarters (legal under Omaha’s Municipal Code). The event was scheduled about a week after Omaha police arrested nearly 130 peaceful protestors en masse, including Vondrasek. With this context, one officer used a bodycam to record his conversation with Vondrasek before the event. And Detective Garro of the Narcotics/Intel Squad provided information about the gathering to multiple members of the department in the days prior.

NOISE directed a question to Lt. Sherie Thomas specifically about the chalking event. “Given your years of experience in law enforcement, can you explain why the possibility of a sidewalk chalk event was something that warranted the attention of a member of your Narcotics/Intel Squad?”

Lt. Sherie Thomas responding on behalf of OPD emphasized their efforts to stay informed of large events as “Any event that may have a large number of people attend is information relative to the safety of the city,” and clarified, “Open source intelligence was used (i.e Facebook announcements etc) to learn of events that may bring a large number of persons together.” The chalking event drew a crowd of about 50 people. Similarly, department emails suggest roughly 50 people said on Facebook they would attend Ja Keen Fox’s birthday party.

NOISE also asked Lt. Thomas to offer an explanation for the surveillance of primarily Black activists given that decades of such practices have led to a mistrust of the police within Omaha’s Black and Brown communities. Lt. Thomas responded on behalf of the department, “The Omaha Police Department supports First Amendment and social justice concerns and is desirous of assisting to facilitate a peaceful event and expression of thoughts for all involved.”

None of the activists or organizers who spoke to NOISE were surprised to hear their social media accounts were being watched by numerous members of the Omaha Police Department. Bear Alexander acknowledged the surveillance saying at the end of the day, “We are fighting to change a system that the government and local law enforcement are fighting to maintain.” And when Vondrasek spoke to NOISE he concluded, “Every moment they’re like, worrying about me is a moment they’re not following another Black activist around.”

*Correction: a version of this previous story stated, “officials at the county jail” were in communication with OPD, however representatives from County Corrections wish to clarify that it was not an employee of Corrections.