Revisiting Out of Omaha Pt. 2: A Time for Learning

By Leo Adam Biga

Dreams too often get deferred when living in poverty. They don’t have to be, according to the critically acclaimed 2018 documentary, Out of Omaha. Protagonist Darcell Trotter kept putting his aspirations of an entertainment career on hold, while still embroiled in the day-to-day survival mode of inner-city North Omaha life.

The film details how he eventually took himself out of harm’s way by joining his twin brother, Darrell, in Grand Island, where they’ve both found a fresh start. Since then, as a result of the film making him a public figure and his show business dreams known, Darcell is now finding opportunities to make those dreams more of a reality.

Part II

Darcell Trotter as “Bobo” in A Raisin in the Sun

The winter of 2019 saw Trotter take a big step toward his goals when he auditioned for and was cast inn the Omaha Community Playhouse’s production of A Raisin in the Sun. His work in the play marked a melding between his own story and that of the Lorraine Hansberry drama of African-American aspirations dashed on the shores of bigotry and discrimination. The frustration and hope at the heart of the play are close to Trotter’s own experience.

“Honestly, my heart’s in music, acting and film and everything like that,” Trotter says, “and I’m excited about it because I really believe if I stick to it, put my mind to it and go all the way, fully with it, I’ll be alright. I definitely want to take acting more seriously than I have ever [done] before. That’s what I’m looking at getting myself into.”

“Creative friends are all pushing for me to really pursue my art. I’m in a position now where I’m balancing out everything.”

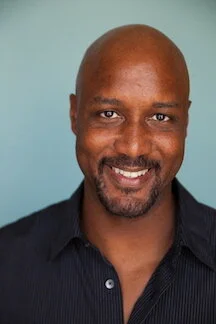

Tyrone Beasley, Director

Trotter hails from a thespian legacy. His uncle, John Beasley, is a veteran stage and screen actor. Trotter’s cousins, (John’s sons), Michael Beasley and Tyrone Beasley, are also working actors.

“It kind of runs in the family,” Trotter says. “For some reason I’m naturally comfortable with the camera. Usually, people aren’t. In Out of Omaha I didn’t feel the need to try to make myself appear differently, like a reality TV star, or nothing like that. I just remained myself.”

Tyrone Beasley, artistic associate, Director of Outbound Programing at the Rose Theater, directed Trotter in A Raisin in the Sun at the Playhouse. He feels his cousin has a place in the “family business.”

“This was the first time he’d done anything like this,” Beasley says. “It was a real commitment because he was coming from Grand Island for rehearsals. He said this is something he really wanted to do and in which he was really interested; and he proved that with the commute alone. He reinforced that with the growth in his work. With each rehearsal he came with something new rather than just learn his lines by rote. He obviously did his homework. That was really impressive.

“He had tremendous growth over the whole process. He just continued to work on his character (Bobo). Also, he’s great at following direction, which isn’t always easy for an actor to do. He was present. He asked questions. He brought stage presence. I think he’s committed to being the best actor he can be and not settling.“

In Out of Omaha Trotter displays resilience butting up against roadblocks. Beasley saw the same trait during the play. “The things he showed in the documentary, he showed me. The documentary is his life and he brought that to the stage. I think he’s got a real future.”

Skylar Reed also known as, Scky Rei

Trotter’s lifelong friend Skylar Reed, alias Scky Rei, whose rap career has taken off, in part due to the film, noted Darcell’s discipline.

“Every other day I was on the phone talking to him and he was back home studying his part and commuting to Omaha to rehearse. He didn’t have a major part but he had a key part and he treated it like it was the lead, and it showed in his performance. I got to see him the very last show when he was all sharpened up, and it was beautiful,” said Reed.

John Beasley himself sees his nephew’s potential and is actively advising him on his career pursuits.

“As you see from the documentary he’s got quite a personality. I’m just trying to get him to be who he is. He is a natural. I talk to him from time to time and give him a tip here and there. I tell him don’t try to change too much, just have it in you to be yourself,” says Beasley.

The same career advice he gave his sons, he gives Trotter.

“Basically what I instilled in those guys is that it’s possible to do anything you want if you put your mind to it and don’t let anybody talk you out of it. Go ahead, see your dream and follow it.”

Beasley is also teaming with musician Arno Lucas “to get Darcell’s music out there.” “Darcell is a pretty good artist.”

With so much momentum, it may come as a surprise that Trotter almost didn’t finish the film that’s changed his life.

“The process wasn’t easy at all. There were moments through the years when I questioned should I be doing this, is this something I want to keep doing,” he says. “The producers said if you don’t want to do this, we’ll still be your friend and be here for you. I’m very glad I stuck with it because it allowed me to see my growth as a human being and to see all the mistakes I’ve made, how far along I’ve come, and how far I still have to go,”

Jef Johnston, mentor to Darcell Trotter.

“He’s not a finished product,” says mentor Jef Johnston.

As the film’s production played out over such a long period, some dynamics portrayed in the film changed.

“I went into it with the understanding the stakes were high and relationships might change,” Trotter says, “Some of those relationships are different today than how they were in the film. For example: my daughter’s mother and I have a great relationship now.”

The film has found receptive audiences wherever it has played. But Jef Johnston, whose son, Ryan Johnston, produced it and whose former job at Avenue Scholars Foundation put him in close contact with Trotter, feels it’s been ignored by those who most need to see it.

“I don’t think the media here really embraced it,” Jef Johnston says. “I don’t think white people really want to hear about white privilege, and that’s too bad. They love the idea of kids pulling themselves up by the bootstraps, but they really don’t want to delve into it too deeply. That’s a problem. West Omaha churches and rotaries should be showing it.”

Says John Beasley, “I think it’s a film everybody should see.” He also feels that by documenting urban problems that the rest of the country doesn’t associate with Omaha the film offers up the city in a new, not-altogether-favorable light. But its harsh truth is undeniable and replicable, “It’s opening the world up to Omaha,” he says. “That Omaha is a city with the same problems and disparities, with the haves and the have-nots, as any large city. Darcell’s story is the story of Black life all over this country,”

Those who had a hand in Out of Omaha know they participated in something special and that its message is bigger than any of them.

Wayne Brown, an Urban League of Nebraska staffer who has helped guide Trotter since the film’s inception, feels the film derives much of its power from the immersive, profoundly deep dive it takes into Darcell’s then-chaotic life. The hyper-personal, unvarnished look makes us feel that we are there as emotion-laden events unfold onscreen.

“Whatever was going on was what was actually happening in my life. There were some intense moments,” Trotter says.

Bearing it all entailed a calculated risk.

“I knew there was a possibility certain people in my life might take it out of context, and it could put some strains on my relationships,” he says, “But that was a risk I was willing to take, for my story to get out to the masses, and to let the next person walking in my shoes to take from it what the film’s various scenarios presented.”

“It was definitely a struggle. I said to the producers, my story isn’t done, I don’t know if it’s worth documenting, and they would tell me, bro, your story is powerful – it might not seem like much to you, but to us and others it definitely changed our way of looking at things and woke us up to make us look at ourselves in the mirror.”

Trotter eventually took the long view. “I thought of it from the aspect of my daughter and as she gets older she can see that her father was a part of something that was bigger than me that possibly with help can change the world,”

Brown got involved in the project for a similar big picture goal.

“We thought we could do something more than a movie, we could do a movement. That we could scrape away policies, blame, the pulling up of the bootstraps narrative – like seriously if you were in this situation, what would you do? – that roller- coaster-ride that feels like it’s out of anyone’s control. What can we do to make life more intentional? How can we make those ups and downs less traumatic on young people? There’s individual trauma from those events and then there’s systemic trauma from those events.”

Brown feels the film frames the conversation America needs to have about racism. Screenings and discussions are a good start.

“When black, brown, white people see this film in the same room we have this emotional, historical, integral experience together, and we can come out talking about these issues in a different way.

Whenever there’s a screening I’ll go because the conversation that happens after going through that experience is so robust. No one talks about politics at those times, We talk about how we can help other humans. So those screenings are powerful,” says Brown.

Producer Ryan Johnston says his hope for this film is “that as many people as possible will see it and take the chance to walk in Darcell's shoes a little while.” He adds, “When you do that, some of the more simplistic narratives of ‘this is America and if you just work hard and pull yourself up by the bootstraps’ fall away.”

Darcell Trotter has his own take on what value the film has for provoking discussion and action.

“When we don’t take the time to understand and to have that dialogue we just kind of write each other off,” he says. “But this film allows people to see that the kids in North Omaha aren’t that much different than the kids in Millard or Grand Island. It’s just that in North Omaha they don’t have as much of a support system like they do out west.”

“When people see the film they see that I’m actually a good human-being, and not a terrible person. I didn’t have a support system and I unfortunately had to do certain things, sometimes just to be able to survive. People are able to relate to that.”

Without dialogue, Trotter sees no clear way forward, addressing the underlying conditions and policies that (are meant to) keep people down.

“As long as we, as a country, don’t have the conversations that we should be having, so that we can move forward with things, we’ll still have systemic racism and oppression, people making assumptions about other people because they don’t want to take the time to understand others.

Typically, when you don’t understand something, you fear it, and that’s how it is in Omaha.

“A lot of poverty comes from lack of education, so I feel that if we can really emphasize financial literacy, strengthen the community, strengthen relationships between parents and teachers; we can all be on the same page. As a city we need to come together to have communication. I feel like we should have events where we do have these conversations and start really challenging ourselves to be more hands-on with our community. We have to stop thinking ‘it’s not my problem, it’s your problem’, when really it’s everybody’s problem. It’s more than just funding something. It’s actually going along and being hands-on with people.”

Brown says it’s a process. “It took us a while to get here to make the system the way it is. It’s going to take an equal amount of hope and community and change to help bring people back from the brink.”

Darcell Trotter and Out of Omaha executive producer and hip-hop artist, J. Cole

Trotter’s often asked to attend public screenings of Out of Omaha, to be part of talkbacks, or to share his story about the making of the film, and his life after it. As personal appearance and speaking requests continue coming in, his uncle’s urging him to charge a speaker’s fee.

“He didn’t receive any financial compensation from this film,” John Bealey says, “so he needs to be paid for his speaking engagements and things like that. And he does have something to say. He is quite a gripping speaker on the subject.”

The film will surely continue speaking to people. Only time will tell whether its themes are still relevant, generations from now, or if America and Omaha find redress for those who remain unheard.

Visit the film’s website at fireflyinc.com. Watch the trailer at firstshowing.net. Stream the movie on Amazon, Hulu, etc.