Black Men Out: African Americans in Baseball

The CWS begins on Juneteenth this year, emphasizing the lack of Black players in the sport today.

But Black Omaha's contributions to the game run deep with Hall of Famer Bob Gibson and four generations of Bartee family ballplayers.

On the first day of the College World Series (CWS) it’s time to look back at segregation in baseball, the legacy of the Negro leagues, breaking the color barrier, and how Negro Leagues legend Buck O’Neil carried the banner for Black baseball.

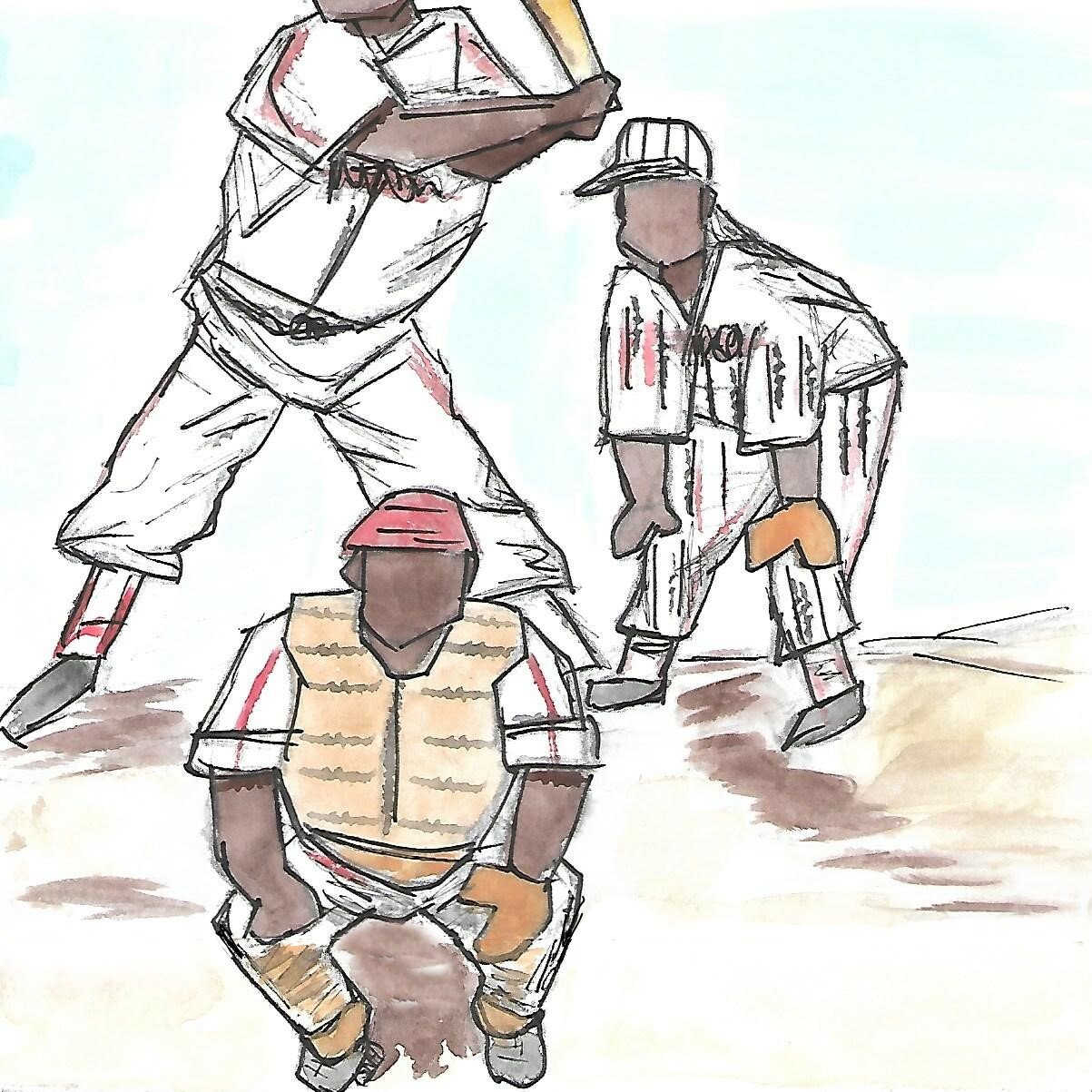

Illistration by Stephanie Hanson

by Leo Adam Biga

Any mention of Omaha and the Boys of Summer is bound to stir up the name of native son Bob Gibson. The Baseball Hall of Famer, who died last fall at age 84, made such an indelible impact on the game that even in death he remains arguably the greatest gift the city’s given the sport. Close behind is the City of Omaha serving as host of the College World Series since 1950. For most of that span the CWS unfolded at Rosenblatt Stadium, demolished in 2012. Since 2011 the series has called TD Ameritrade Park home. The 2021 series runs there June 19–30.

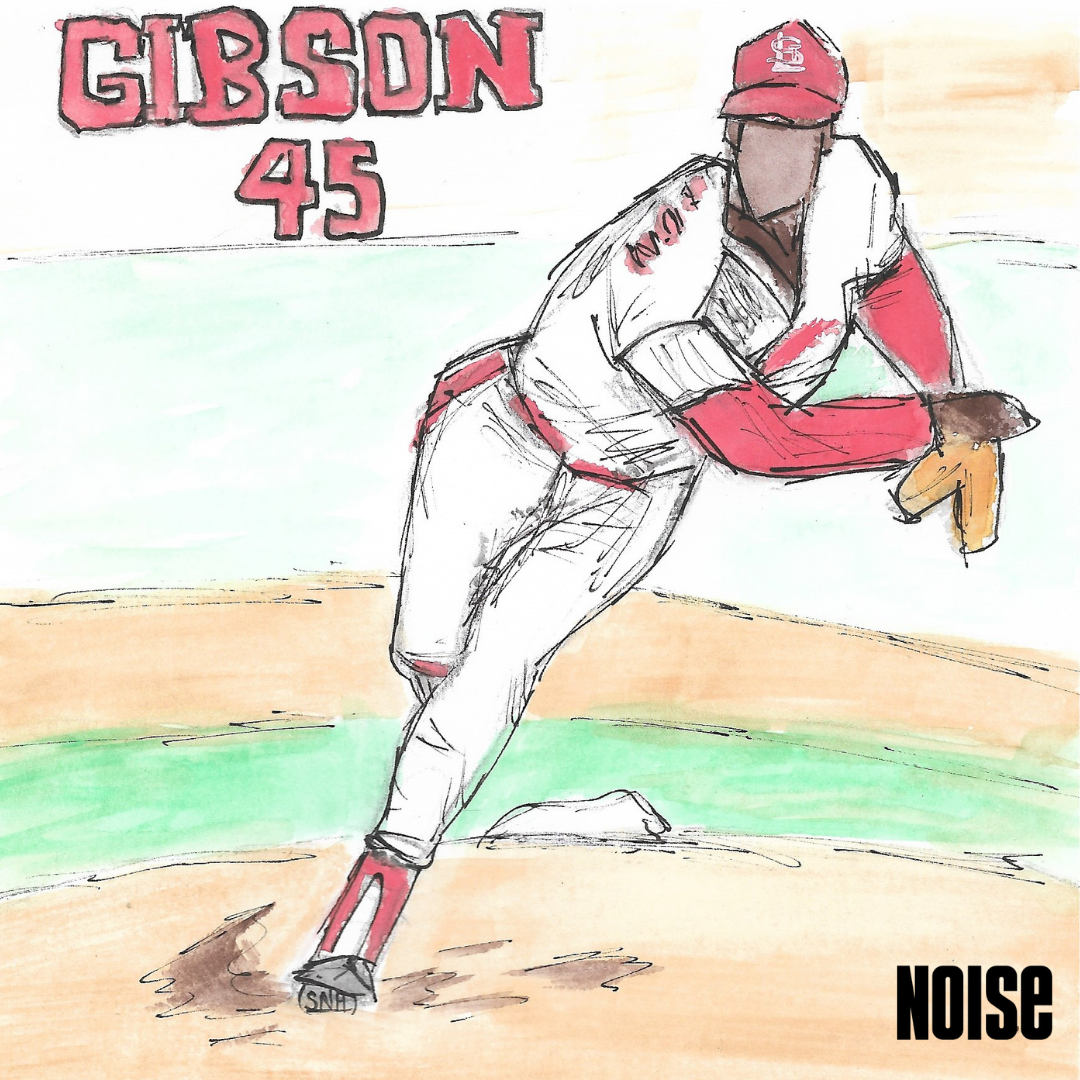

Artist credit: Stephanie Hanson for NOISE

Gibson, a Black man from Omaha, became one of professional baseball’s most honored legends, while the mostly-white CWS has become the game’s amateur mecca. The contrast is a reminder of the historical disparities plaguing the sport. When Gibson ruled the mound for the St. Louis Cardinals in the 1960s and 1970s, African Americans represented a real force in the game as measured by sheer numbers and contributions. At the zenith of their participation in the ‘70s-‘80s, Black players constituted 18 percent of Major League Baseball (MLB) rosters. This despite the big leagues only being integrated in 1947. Now, just two generations from that peak, their participation is in single digits. Segregated baseball was the norm in America until Brooklyn Dodgers general manager and co-owner Branch Rickey signed Jackie Robinson in 1945.

In 1947 Robinson joined the big league club, thus defying an unwritten rule barring Black players from the majors since the late 19th century. Responding to that exclusion, African Americans created their own baseball universe. In 1920 Andrew “Rube” Foster — “the father of Black baseball” — instituted the Negro National League, the first organized Black pro league. Other Negro leagues followed. The hope was the big leagues would eventually take-in one team from each main Negro league. It never happened. But the Negro leagues continued to prosper. The boom was from 1933 to 1947, with teams in Kansas City, St. Louis, Indianapolis, Chicago, Detroit, Cleveland, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, Birmingham, Memphis, Baltimore, New York, et cetera.

Omaha even fielded its own semi-pro, independent Negro league team, the Rockets, in 1947-1949.

After finally gaining access to the majors, Black players collectively asserted themselves as difference makers. Some individuals, such as Gibson, stamped themselves as all-time greats. Instead of that progress continuing or holding steady, Black participation in the game has plummeted at every level. College baseball’s predominantly white demographics are hard not to notice during the CWS. Exclusion extends to coaching, managerial and front office posts, where minorities are grossly underrepresented as they have been historically.

Gibson played his entire 17-year MLB career with St. Louis. The hometown icon maintained an Omaha residence during his playing days and still made this his home during a second career as a Cardinals coach and broadcaster. His son Chris followed his footsteps into professional baseball. Gibson held stakes in a local Black-owned radio station and bank and owned his own bar-restaurant. He helped dedicate the Bryant Center. He hosted a charitable golf tournament. Parades and organizations celebrated him. He’s in the inaugural classes of the Nebraska Black and Omaha Sports halls of fame. A sculptural likeness of him stands outside Werner Park. He appeared at a 2016 Baxter Arena gathering of fellow Omaha Black sports legends Marlin Briscoe, Roger Sayers, Ron Boone and Johnny Rodgers.

Even long after retiring as a player in 1975, his name came up each summer as the baseball season moved into high gear and the CWS unfolded. Anticipation runs high for this year’s series as it marks the return of an annual tradition interrupted in 2020 by pandemic concerns. This city’s seven-decade association with a major sports championship is unprecedented in NCAA history. Teams, fans and media from around the nation generate a multi-million dollar economic windfall for Omaha. ESPN coverage adds brand value.

The CWS is not just a showcase for college baseball but for the sport itself. Some participants go on to play professionally. A few make it to the majors. Several CWS veterans are on current MLB rosters, including former Arkansas star Andrew Benintendi, who plays for the Kansas City Royals. In addition to the CWS, Omaha owns a long history as home to Triple-A baseball. It hosted minor league affiliates of the Cardinals and Dodgers before becoming the site of the top farm club in the Royals organization in 1969. The Omaha Storm Chasers remain its top affiliate.

Although Gibson played in three MLB World Series, his Creighton teams never made it to the CWS. The only time CU qualified, 1991, Omaha native Kimera Bartee was on the team. The son of former CU player and coach Jerry Bartee made it to the pro ranks like his father before him but surpassed him by reaching the big leagues.

Bob Gibson: King of the Hill

Bob Gibson baseball card Credit: Society For American Baseball Research

Two and a half decades earlier, on the eve of the civil rights era, Gibson made his historic mark. He attained everything possible in his career: World Series titles, the Cy Young Award, regular and post-season MVP honors, All-Star selections, 20-win seasons, leading the league in shutouts, complete games, ERA, posting 200-plus career wins and 3,000-plus career strikeouts. In a ’68 season performance for the ages, he posted a 1.12 ERA and recorded 13 shutouts. Arguably the greatest World Series pitcher ever, he started nine series games, completed eight, compiled an overall 7-2 record, a 1.89 ERA and two MVPs.

A dominant power-pitcher with exceptional control, he was also an iron man in an era when quality starting pitchers were rarely relieved, racking up 255 career complete games and 56 shutouts. Considered one of the greatest athletes to ever command the mound, he earned several Gold Gloves for his defense. He was also one of the best hitting pitchers of his generation (he homered in two separate World Series), finishing with 24 career regular season home runs and an impressive 144 RBI in a little over 1,000 at-bats. Anyone who knew what made Gibson tick remarks on his ferocious competitiveness and intensity. This ultimate intimidator owned the inside part of the plate. It was his domain and pity the batter who challenged him there. His sustained brilliance across two decades resulted in first-ballot enshrinement in Cooperstown.

Jerry Bartee, who played at Omaha Central before going on to Creighton, summed up Gibson’s impact: “You just don’t have a talented athlete of that caliber and not have a legacy left behind, and for him it’s one of determination, confidence, fearlessness and “Hey, man, I’m-going-to-give-you-my-best-every-time-I-step-out-there.” Bartee, 73, and chums grew up idolizing Gibson. “He was a role model for many of us young Black athletes, especially those of us that loved baseball. He represented us. We wanted to be like him.”

Like some Omaha peers, Gibson grew up in a public housing project. His older brother Josh was a respected coach. Realizing his kid brother’s potential, he spent extra hours drilling him in what it takes to be a winner. It was under that tutelage he learned to never give an inch. Gibson was a multi-sport athlete, playing basketball and baseball for the Y Monarchs, Omaha Tech and Creighton. He signed with St. Louis in ’57, a mere decade after Jackie Robinson broke the MLB color barrier. He played a season with the Harlem Globetrotters, before committing full-time to baseball. After a stint with the Triple-A Omaha Cardinals, he made his big league debut in 1959.

Black Men Out

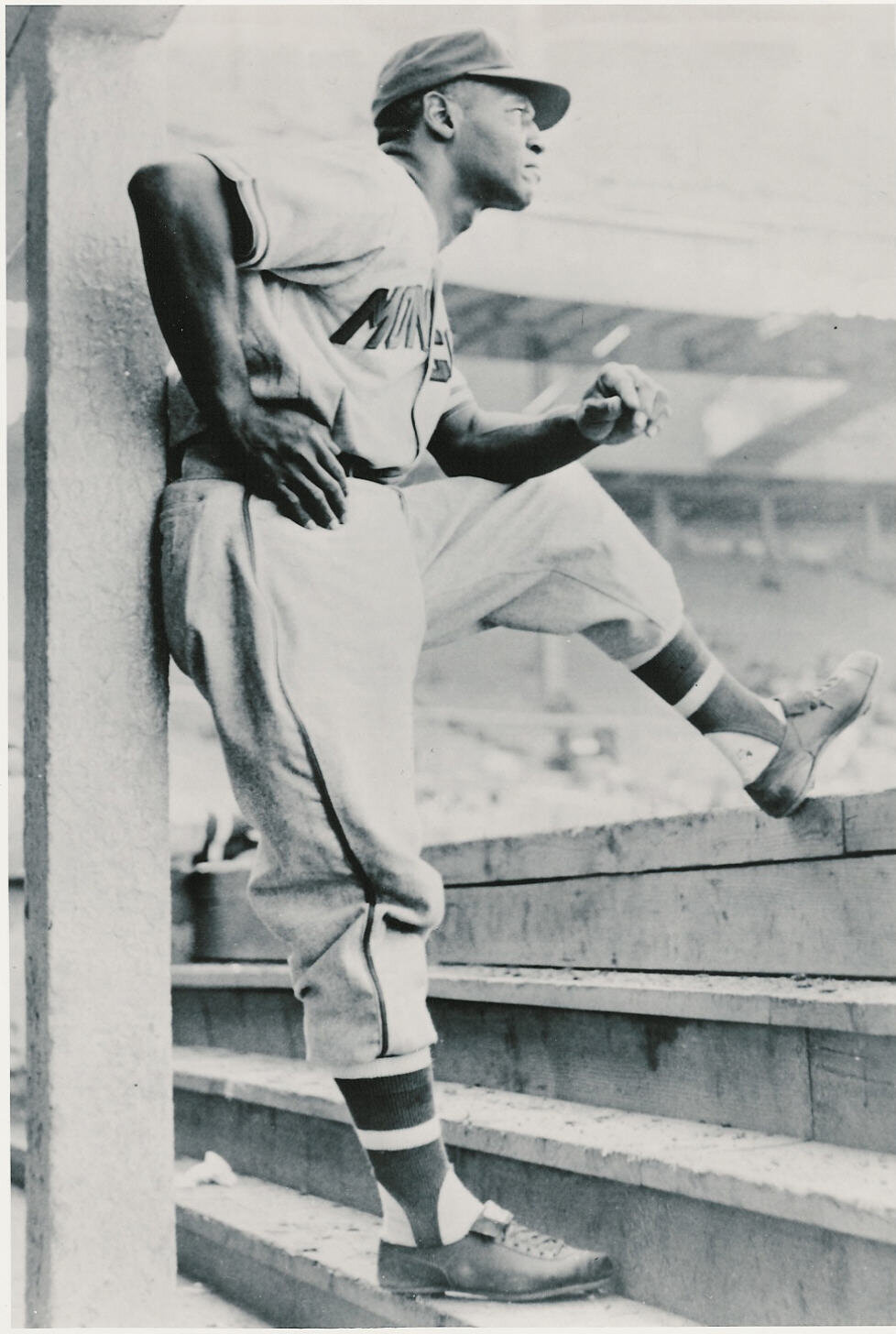

A young Jerry Bartee with a teammate Credit: The Omaha World Herald

Gibson knew well the impediments Black men faced trying to gain equity in the national pastime, He was among a wave of players, some with roots in the Negro leagues, given opportunities to advance to baseball’s highest level. The fact he made it as a starting pitcher went against all the odds because Black starting pitchers then and now represent a rarity – not unlike Black quarterbacks once were in football. By the early ‘80s, Black players were trending to be a quarter of major leaguers. Today, they account for about 7 percent of MLBers and 5 percent of collegians. There are often more white and Latinos players than Black players on Historically Black College and University teams. In an era when racial disparities are under assail, baseball’s taken several steps backward. The same disparities are seen in women’s softball. Experts cite history, culture and economics as reasons. While MLB invests heavily in grooming Latinx and Asian players abroad, it devotes scant resources at home. Meanwhile, youth baseball’s transitioned from neighborhood-based Little League to elite travel teams and exclusive academies whose costs are out of many families’ reach. Organized inner-city baseball is nearly extinct.

“For me not to see young Black kids involved in this game saddens me. The game is that great and I know these kids are capable of being very successful in the game. Many of them could have an opportunity to make a great living in the game.” said Bartee, who learned baseball from his elders. “My mother’s two brothers played semi-pro ball. They introduced me and my cousins to baseball. That’s what we’re lacking today – the game being handed down through the generations. That love for the game used to be there” in Black families and communities.

The familial, affinity connection Black fans and athletes once felt for baseball was nurtured by the Negro leagues, which fostered Black pride and generated Black commerce. With those teams only memories, Black MLB stars rare and few Black youths and adults involved in the game anymore, the sport no longer exerts the pull it did. As each succeeding generation lacks a direct tie, Bartee said, baseball’s ever more an after-thought. “The hole gets deeper and deeper.”

Jerry Bartee Credit: The Central High School Foundation

As a Black baseball family, the Bartees are an anomaly. Since retiring as a player, Jerry’s oldest son Kimera has worked as a scout and coach for various MLB organizations, including the Pittsburgh Pirates. He’s now a roving scout for the Detroit Tigers. Kimera’s younger brother Khareth also played high school, college and pro ball and is now a hitting instructor. Kimera’s son Amari, who will play for George Washington University next season, is the fourth generation in the sport.

“With my boys, they were around baseball because that’s what I did,” said Jerry.

As the Black experience with baseball has waned, it’s grown exponentially in basketball and football. When Black players do emerge as stars in baseball, some suggest they aren’t promoted as aggressively as their white counterparts. More exposure and access to the game could help give it the platform it lacks in Black communities.

American baseball elitism has extended to branding. For example, MLB’s “World Series” was hardly a global event until the 1990s influx of players from Latin America, South America and Japan made the game more truly international. Ironically, indigenous U.S. players today face a competitive disadvantage, Bartee said, compared to Latinx nation prospects, who make baseball a year-round focus. Passion for the game runs deep in places like the Dominican Republic, where it’s widely viewed as a pathway to opportunity, which is what it once represented to African Americans.

Buck O’Neil: Ambassador for Black Baseball

Buck O'Neil Image credit: Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City

A figure notably absent from diamond conversations these days is the late Buck O’Neil, the face of the Negro leagues as a former Kansas City Monarchs player and manager. Back in the day, O’Neil traveled to Omaha for barnstorming games. The Monarchs tried signing the young Bob Gibson, but the prospect of joining a big league club was more attractive than the Negro leagues. In his retirement O’Neil often visited here to promote the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum he helped found in Kansas City.

A Negro leagues Baseball exhibition is now on display at the Great Plains Black History Museum, 2221 N. 24th Street.

O’Neil loved being a Negro leaguer. “The only experience I would have traded it for would have been to have done it in the major leagues,” he said. He enjoyed recounting the Negro leagues experience. “All you needed was a bus and I’ll tell you what, we traveled in some of the best money could buy during that period. And we stayed in some of the best hotels in the country — they just happened to be Black-owned and operated. We ate in some of the best restaurants in the country,” proclaimed O’Neil. “In that bus you’d have 20 of the best athletes that ever lived. To be able to play, to participate, to compete with these type of athletes, oh, it was outstanding.”

Athletes and musicians were celebrities in Black communities. They socialized together. “At the Streets Hotel (in K.C.) I might come down for breakfast and Duke Ellington and them might be there and say, ‘Come over and have breakfast with us this morning.” Or Sarah Vaughn. You’re talking jazz and baseball. That was Kansas City.”

When the Monarchs were at home in K.C., they were feted like royalty. “Yeah, we were very well respected,” O’Neil said. “I’ll tell you how much — I courted a preacher’s daughter.” Churches deferred to their schedule. “Sunday, 11 o’clock service, but when the Monarchs were in town, service started at 10 o’clock so that they (churchgoers) could get to the ballpark. And then they would come looking good — dressed to kill. It was actually not only a ball game, it was a social event. The Monarchs, this was the thing. You saw everybody that was somebody there at the ballpark. People would hobnob with their friends.

Notable Negro leagues teams that passed through Omaha caused a stir. They stayed at North O Black boarding houses or hotels. A local boarding house run by the Trimble family often hosted touring musicians and Black ballplayers. Von Trimble recalled as a child playing catch with Negro leagues legend Satchel Paige.

Black teams held their own with major league teams in exhibitions. “We wanted to prove to the world they weren’t superior because they were major leaguers and we weren’t inferiors because we were Negro leaguers,” O’Neil said. Besides, he said, major leaguers “couldn’t afford to twist an ankle or break a finger in an exhibition ballgame.”

“We wanted to prove to the world they weren’t superior because they were major leaguers and we weren’t inferiors because we were Negro leaguers,”

Home or away, O’Neil said he and his fellow players felt the passion of fans.

“The Rev. Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. at his Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem, New York, preached a baseball sermon for the New York Cubans, the New York Black Yankees, the Kansas City Monarchs and the Memphis Red Sox before a four-team doubleheader at Yankee Stadium,” he said. “He preached that sermon, and man, the church was full. They followed us to the ballpark. We had 40,000 at Yankee Stadium. We played over at Branch Rickey’s place” — Ebbets Field – “and we had 20,000 there.”

Artist credit: Stephanie Hanson for NOISE

When Robinson was signed away from the Monarchs in 1945. O’Neil said it was a sound commercial move. “Branch Rickey, the astute businessman that he was, saw this as a brand new clientele.” O’Neil felt the men who broke baseball’s color barrier helped spark a social revolution. “That was the beginning of the civil rights movement. That was before Brown versus Board of Education. That was before sister Rosa Parks said, ‘I won’t go to the back of the bus today.’ Martin Luther King, Jr. was just a sophomore at Morehouse (College). Jackie started the ball rolling right there in baseball.”

In O’Neil’s opinion, “What kept us out of the major leagues was in fact not the fans, but the owners. See, the baseball fans, all they ever asked — Could you play?” The success of Robinson, Larry Doby, Willie Mays, Hank Aaron, Roy Campanella. Don Newcomb, Ernie Banks, Frank Robinson, Willie McCovey, Lou Brock, Bob Gibson and many others proved Blacks belonged on the same field, paving the way for others to follow. MLB tapped the thinning Negro leagues’ talent pool. Devoid of stars, Black teams folded and then entire leagues disbanded. The last survived into the early 1960s. By then, Black players were regarded as essential cogs to any successful MLB franchise.

What Goes Around, Comes Around

“The Story of Negro League Baseball” is on display at the Great Plains Black History Museum

Black players once led the way diversifying the sport. But over time Latinx players supplanted them as the hot new minority. The sport’s biggest stages, from MLB’s World Series to the CWS, represent the conspicuous absence of African Americans – the smallest racial minority in the game next to Asians and Native Americans.

Jerry Bartee finds it ironic that the same organization (now the Los Angeles Dodgers) that broke the color barrier has only three Black players on its 26-man roster today. The current roster of any big league club reflects that same reality. So do the rosters of most high school, American Legion, collegiate and minor league teams. It gets back to economics. To receive the best training and most exposure, a player must belong to a select team or academy program. In Black communities, there have to be African Americans who played the game coaching it.

Baseball’s been notoriously slow adjusting to diversity, equity and inclusion trends. Gibson argued decades ago the sport simply mirrored society’s reticence or resistance to change. Even though Black players were fixtures in the majors by the time he arrived, certain organizations ignored the changing face of the game, notably the Boston Red Sox and New York Yankees. The Cardinals were more progressive than most organizations but Gibson and Black teammates still endured racial slights. That was especially true in the Jim Crow South, where segregation was part of the experience of coming up through the minors when playing south of the Mason-Dixon. Spring training in St. Petersburg, Fla. presented similar segregationist challenges.

Gibson confronted blatant racism during a brief ‘57 stay with the Cardinals farm team in Columbus, Georgia. “I was there for three weeks, but that was a lifetime,” he said. “I’ve tried to erase that, but I remember it like it was yesterday. It opened my eyes a little bit, yeah. You can see movies, you can hear things, but there’s nothing like experiencing it yourself.” His playing career coincided with the nation’s civil rights struggle, when change in baseball, as everywhere else, came slowly. The franchise adhered to custom at its spring training complex by having Black and white players stay in separate quarters. By the time he was firmly established in the ‘60s. he and teammates Lou Brock, Bill White and Curt Flood complained enough that the Cards flaunted local laws by instituting integrated quarters.

Bob Gibson, an Omaha native, played baseball and basketball for Creighton University. Credit: Creighton Athletics

In his book Stranger to the Game Gibson described the camaraderie in the club as “practically revolutionary in the way it cut across racial lines.” Perhaps the best testament to it was his friendship with former Cardinals catcher and network sportscaster Tim McCarver, a Southern-born and bred white, who credits Gibson with helping him move beyond his bigotry.

The brotherhood the Cardinals forged then, Gibson said, could be a model for America today. “Just like it happens in sports, it can happen in other aspects of our lives, but people won’t allow it to. They just won’t allow it. A couple of my best friends just happen to be white. Now, I don’t know if I hadn’t been playing baseball if that would be possible. It could be…I don’t know.” He added the special feeling between him, McCarver and their old teammates “will always be there.”

Gibson felt it hypocritical to make baseball a scapegoat for what he saw as systemic problems. “The problem with racial prejudice goes far beyond baseball. When people talk about the lack of Black managers and coaches, I just laugh, because we’re talking about a sport where we’re supposedly accepted. But you get into the business world, and we’re not accepted. We’re only able to go so high and then we’re limited to making some lateral movements.”

Kimera Bartee is the exception when it comes to African Americans in baseball. He’s made a career of the game on and off the field, though he’s seemingly hit a glass ceiling. “I’m very proud of him,” Jerry Bartee said of his oldest son. “Baseball is his life. He’s made a good run of it.” But for all the time he’s put in, at age 48 Kimera’s not yet gotten the opportunity to run an organization or head a front office department.

The same opportunities alluded Gibson. He acknowledged progress made in and out of baseball, but saw room for improvement: “Some of the problems we faced when Jackie Robinson broke in and when I broke in 10 years later don’t exist, but then a lot of them still do. I think people are a little bit more sophisticated now in their bigotry, but they’re still bigots.” He lauded then acting MLB commissioner Bud Selig’s pledge to hire more Blacks in administrative roles, but remained skeptical: “Saying it and doing it is two different things.” The numbers have borne out Gibson’s skepticism. Of MLB’s 30 teams today, only two have Black field managers and none have a Black general manager.

Gibson knew he paid a price for being a Black man who dared to speak his mind and go his own way. It’s why he chose Stranger to the Game as his book’s title. “I’ve found out that people don’t want you to be truthful about most things. People don’t like honesty. It hurts their feelings. But I don’t know any other way. I’ve been basically like that all my life – blunt. Definitely.” He fought “the racist thing” over his lifetime. He complained openly about Omaha’s lack of racial progress. He and his first wife, Charline, encountered red lining restrictions here. Charline was active in public forums dealing with social issues. He never backed down, never gave up. That calloused exterior helped him endure various slights, like being denied a promised Anheuser-Busch beer distributorship by former Cardinals’ owner, the late August Busch. Or waiting 20 years before being brought back as a coach. Or finding employment-investment opportunities closed to him in Omaha and then seeing various business interests go sour. Publicly, he bore the snubs and disappointments with characteristic stoicism. Through it all, he remained faithful to his hometown and his sport, even though he never felt completely at home in either.

“He meant a lot to this community, to the city of Omaha, even though back in the day he wasn’t totally embraced by certain segments,” Jerry Bartee said. “But he never forgot where home was. His legacy will live forever.”

The dedication in Gibson’s book sums it up: “To my son … May your life be as rewarding as mine, and, I hope, a little easier.”

“To my son … May your life be as rewarding as mine, and, I hope, a little easier.”

EDITOR’S NOTE: Quotes from Bob Gibson and Buck O’Neil are drawn from interviews that writer Leo Adam Biga conducted with these baseball legends in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

For more information:

Great Plains Black History Museum

University of Lincoln archives

More From Leo Adam Biga on the Legend of Buck O’Neil