The Beasleys: A Family that Sows Together, Reaps Together

Black Legacy Families Series: Installment IV

John and Judy Beasley in Cape Town, South Africa during the filming of "Spell.”

By Leo Adam Biga

Creativity cuts across generations of Omaha African American families. The Metoyer, Eure, Love, Allen, Rogers, Jeanpierre, Valentine, Partridge, LeFlore, Tyree, Smith, Adams, Higgins, Jordan, Jackson and Berry families are synonymous with Omaha arts. Perhaps no Black family here owns a creative lineage spanning as many disciplines as the Beasleys. They are variously actors, directors, writers, singers, musicians and artists. Four family members have done national stage and screen work. If you count athletics as a form of self-expression, then their exploits grow larger yet.

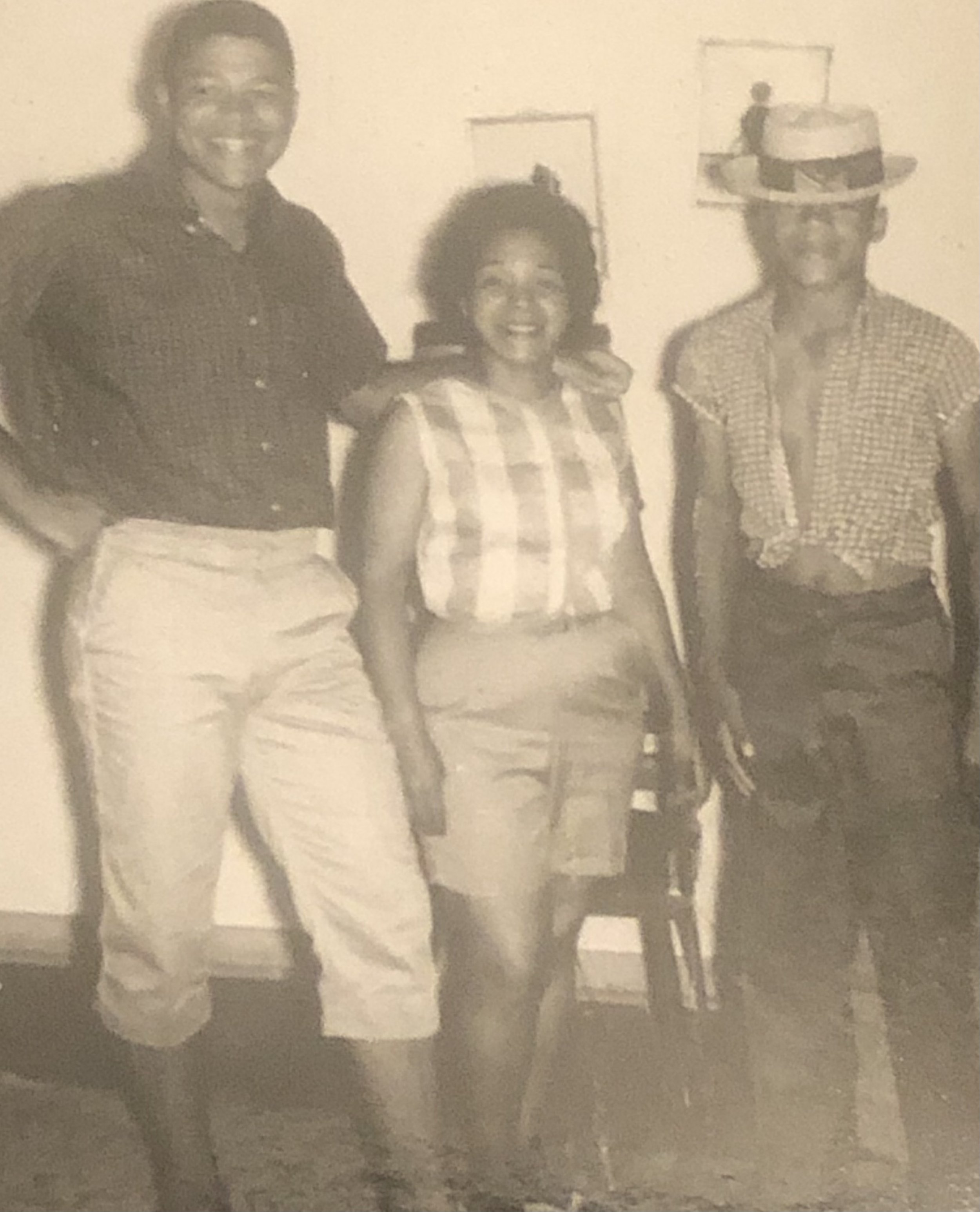

John Beasley with mother Grace and brother Gary in the 1950s.

“It’s the ultimate validation of my acting career,” he said. “Broadway’s always been that vision.” Doing it now, he said, “means quite a bit.”

Leading the way is patriarch John Beasley, a veteran stage-screen actor whose recent credits include Limetown, The Mandalorian and Spell. He’s appeared on major regional theater stages and worked in big budget films. He’s acted opposite media legend Oprah Winfrey (Brewster Place) and screen legend Robert Duvall (The Apostle). He’s been directed by theater luminaries Lloyd Richards and Kenny Leon. By this time next year he should realize a decades-long dream of acting on Broadway, portraying the elder Noah in a new musical adaptation of the best-selling romantic novel and hit film The Notebook by Omaha native Nicholas Sparks. The music and lyrics are by singer-songwriter Ingrid Michaelson. The book is by playwright Bekah Brunstetter. The co-directors are Michael Greif (Dear Evan Hansen, Next to Normal, Grey Gardens, RENT) and Schele Williams (Aida, Motown the Musical).

August rehearsals start in Chicago as a lead-up to a spring preview run in the Windy City. Then the company moves to New York for Broadway previews and a TBD opening due to pandemic surge concerns.. Beasley will be 79 by then. Fulfilling a dream at an unlikely age is par for the course, as he’s long defied expectations. “It’s the ultimate validation of my acting career,” he said. “Broadway’s always been that vision.” Doing it now, he said, “means quite a bit.”

It won’t be his first musical. He’s performed in everything from God’s Trombones at Tech High to Guys and Dolls at the Firehouse Dinner Theatre to Crowns at his own Beasley Theater.

He’s the eldest of five sons born to Grace Virginia Triplett and John Wilfred Beasley. His father was a Broken Bow, Neb. native of African American and Native American descent who eventually owned an electrical supply business. An entrepreneurial spirit runs through the family. Maternal grandfather Wade Triplett was the area’s first Black theater concessioner, co-owner of Ritz Cab Co. and inventor of the Cudahy chili brick. Mother Grace was a hairdresser. The Tripletts migrated from Alexandria, La. to South Dakota, then to Omaha.

Passing it On, Carrying it On

John inherited the family’s maverick instinct to do your own thing and follow your own path. He’s passed this independence onto his children, whose own kids are carrying on the legacy.

The youngest of his two sons, Michael Beasley, is an Atlanta-based film-TV actor in his own right. He’s followed in his father’s footsteps to essay recurring roles in Escape at Dannemora, Swagger, Ballers and Bloodline. He’s guest starred on Blackish. He’s played supporting roles in TV movies (Steel Magnolias) and features (The Accountant, Flight, Unconditional).

Miles, Tyrone, Katie, Olivia, and Evan Beasley.

John’s oldest son, Tyrone Beasley, is an actor, a writer, a director and arts leader. He’s appeared on stage and in film. He was artistic director of his father’s John Beasley Theatre & Workshop, then associate artistic director of outbound programs at The Rose Theater. Earlier this year he became the new artistic director for Nebraska Shakespeare.

The father and two sons all share a talent for drawing and painting. Michael once had his own graphic design business. Tyrone’s artwork hangs in people’s homes. He’s also adept at building and painting scenery for theater sets.

The elder Beasley isn’t surprised his sons took his cue to build their own creative lives and careers. “Basically what I instilled in those guys is that it’s possible to do anything you want if you put your mind to it and don’t let anybody talk you out of it. Go ahead, see your dream and follow it. Now they’re both doing what they love to do.”

The Beasleys also prove creatives attract each other. John’s wife of 56 years, Judy, is a musician. She plays violin, harp and piano. She’s minister of music at Hope Lutheran Church and performs with the Intergeneration Orchestra of Omaha. She accompanies John when he takes the lead on spirituals. As a young man he sang doo-wop on Omaha street corners and in nightspots. He even thought music might be his career. His singing at Hope Lutheran and at gospel concerts, he says, marked preparation for the Broadway-bound musical he’ll soon be joining.

“I feel it’s just something I can’t help. It’s something I have to do to express myself and to speak to some of the things going on in the world, in society. It’s one of those things I think that calls you. I mean, I was ready to get away from this and then I got a call, literally”

Michael’s wife Deena is a fellow film-TV actress. The couple play husband and wife in the upcoming Netflix thriller Reptile with Benicio Del Toro, Justin Timberlake and Alicia Silverstone. She earlier forged a singing and modeling career in Europe. Tyrone’s wife, Katie Shellabarger Beasley, has a custom cake decorating business.

Personal self-expression is both a way of being and a livelihood for the family.

“Art is in our DNA,” said Tyrone. “I feel it’s just something I can’t help. It’s something I have to do to express myself and to speak to some of the things going on in the world, in society. It’s one of those things I think that calls you. I mean, I was ready to get away from this and then I got a call, literally,” said Tyrone, who was close to quitting acting when the phone rang and he got the news that led to a career breakthrough that made him stick with it.

His father agrees artists are called. It’s why he never pushed his sons to try acting professionally. He feels there’s something sacred in the mission he and his family are led to do, saying, “I think through my work I can change souls,”

Deena hails from a Detroit family of entertainers, Upon meeting the Beasleys she found another nurturing creative tribe. “I was very impressed with the family, their dynamics, their careers. how they’ve loving, caring people and how whatever they decide to do, they do it. That’s the background I came from. My parents were extremely supportive of whatever I wanted to do.”

Deena and Michael support each other’s passions. “We’ve been able to live life doing what we love to do and to live life on our own terms,” Michael said. “It hasn’t been easy at times, but we live in the fruits of our labor now.”

Like his father did at Tech, Michael participated in drama at Omaha Central. His dad was in rehearsals as Willie Loman for an all-Black production of Death of a Salesman at the Center Stage when the actor cast as one of the sons, Biff, fell out. John recommended Michael for the part and thus this real-life father and son played fictional father and son on stage. But the acting bug didn’t bite Michael until a similar scenario years later, when filling in for another actor sparked him to make it his career. For a long time though, athletics, not the arts, was his muse.

“For me, it started with tennis and basketball,” said Michael, referring to the family’s dual legacy in sports. The Beasleys’ athletic pursuits span recreational, collegiate and professional participation. His father played college and semi-pro football and worked odd jobs before turning to acting. Michael played collegiately and professionally. His son Malik is playing in the NBA. Thanks to John, the family practiced health, fitness and wellness before it was popular. “Dad was always ahead of the curve,” Michael said.

Gratitude is another Beasley ethos. They know they are among the fortunate few who get paid to do what they love doing.

“I was good enough to be in that one percent who make a living playing ball,” Michael said. “The same with my love for drawing, creating logos, T-shirts. And now acting. It’s always been what I love doing. Deena’s the same way. That’s the beauty of what we’ve been able to do. I learned that in particular from my father and his getting serious about acting as a career at age 45.”

The creative currents don’t stop there. Michael’s step-son from Deena’s first marriage, Darius Brandenburg, is a multi-instrument musician, teacher and composer who recently wrote the music for a hip hop Romeo and Juliet his uncle Tyrone adapted and directed.

The couple’s daughter, Micah, is embarking on her own acting career. Meanwhile, Malik, who grew up on his parents’ sets and acted with his sister in commercials, is carrying another family legacy, athletics, by fulfilling a childhood dream as an NBA player (Minnesota Timberwolves). John closely follows his grandson’s pro hoops career, getting to games as his schedule allows. ”He’s on a really nice journey,” the proud grandfather notes.

Living the Dream

The Beasleys hope their blessings motivate others. “We want people to know it’s possible to live your dream,” said Deena, ”It shows through everybody in our family. We’re all living our dream, doing what we love to do.”

Michael and John Beasley, Loretta Devine, Steve Mululu, Deena and Judy Beasley in Cape Town, South Africa during the filming of "Spell.”

Papa John landing a Broadway role exemplifies not placing limits on dreams. Michael posted on Facebook:

“My father is my hero. He continues to teach me how to pursue and manifest my dreams. He had a lifelong dream of being in a Broadway play but never got the chance. He kept fighting for the opportunity. He could have easily given up, Well, he is now Broadway-bound. No one can ever tell me dreams don’t come true. Continue to fight for your dreams – no matter how long it takes or the obstacles – until you reach them.”

John Beasley and Oprah Winfrey during filming of the movie, "The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks."

Faith is an enduring family theme. John’s uncle David Triplett was a preacher. John’s been a deacon at Hope Lutheran. Wife Judy is a deeply spiritual woman whose “faith walk” inspires her husband and sons. All believe in surrendering things to their Higher Power. “You’ve got to get out of your own way,” said Michael. “Many times when we’re struggling we’re like, God, I don’t know how we’re going to get through this, but we can’t wait to see it work.” “Let go and let God,” Deena added.

Most artists, the Beasleys included, are freelancers who live from project to project. That’s where faith comes in. “The money’s going to come from wherever it’s at,” Michael said. “It always does, too, so we try never to worry about the money. I learned that from my dad.” “It took us a while to grasp that,” added Deena, “but finally we understand what it means.”

Rejection comes with the job. Rather than getting discouraged, the couple invite-expect new opportunities to arrive. “We get to have great experiences because we don’t worry about what could go wrong,” Michael said. “Now sometimes things go wrong, but at the end of the day we get the experience and whatever was the issue gets fixed somehow. We just try to focus on the positive.” Fittingly, Deena hosts a podcast called “Living the Dream.”

Where it All Started

Grace Beasley, John's mother in the 1950s.

John credits his uncle David Triplett with showing him how to hold an audience’s attention. “He used to make up some brilliant, funny stories and tell them to us kids in the neighborhood. He would even make us characters in the stories. When he became a pastor he was a great storyteller in his preaching. I figure that’s where my gift for oratory and dramatics came from.”

John’s own talent was noticed at Tech High, where he became a star speech and theater performer. Military service was a family tradition and after high school enlisted in the Army. Back home, he met his future wife, the former Judy Garner, a Philadelphia native, when she was visiting a sister in Omaha. He got his consciousness raised by Dan Goodwin Sr., Ernie Chambers and other mentors about oppressive measures employed against the Black community. When activist friends convened a press conference critiquing the status quo, he was elected spokesman and delivered a message with dramatic conviction. When the Omaha World-Herald published his name, home address and picture, he became a target. The harassment, including threatening phone calls and law enforcement surveillance, prompted him to move his young family to Philadelphia in 1968.

John Beasley, Cedric the Entertainer and John's cousin David Slaughter on the set of the sitcom "The Soul Man.”

"I've seen the rough side of life, where I thought maybe I might not make it out alive,” John said, “but I always did. It's always turned out. But you've got to stay the course and believe it will work out." “It was a nervous time,” Judy said, “but he didn’t let me on to anything that was really bad.”

For part of their five-year Philly stay, he was a TV producer. The job allowed him to meet superstar guests Sammy Davis Jr., Gladys Knight, Patti LaBelle and Muhammad Ali. From there he went to work as a longshoreman. He briefly joined the Pottstown Firebirds, a semi-pro football team immortalized by NFL Films. It had been years since he was on stage, so to prove he still had it, he auditioned for and won a role in a Germantown Theatre Guild show.

Chris Bartlett and John Beasley on the set of The Mandalorian.

After moving his family back to Omaha in the early ‘70s he took drama classes at UNO and established himself on the local theater scene. While he worked regular jobs – Valmont machine operator, independent jitney driver and Union Pacific Railroad janitor and clerk – he honed his craft in workshops and by doing community theater, TV commercials and industrial film gigs. “There’s no road map, you just have to do it. You step out on faith is what you do. I wanted to be an actor, not an actor-waiter, so waiting tables was not in the cards. I’ve been a working actor all my career. That’s the best you can hope for. Stars come and go, but I’ve never stopped working.”

A testament to how bad he wanted it is that he made road trips of hundreds of miles in all kinds of weather to audition at regional theaters. His efforts paid off with roles at the Mixed Blood Theatre in Minneapolis, the Goodman Theatre in Chicago and the Alliance Theatre in Atlanta. Along the way he became a stock player in major productions of August Wilson plays, culminating in roles at the Huntington Theatre in Boston, Mass. and the Kennedy Center in Washington D.C. He and the late playwright were friends. Even pushing age 80, Beasley never lost hope of making it to Broadway, though it may have seemed from the outside looking in that chance had passed him by.

“I was content, even when I was a janitor, because I was doing what it is I love to do — the theater. There were people who looked down on me and I always said to myself, ‘Well, just wait. I know who I am, and pretty soon you will know who I am.’ I’ve just always felt I could do whatever it is I wanted to do. I’m confident I could have made it as an actor years earlier. But I wasn’t ready at that time to do what it would take. I had a young family I was raising, and I love my family. I love the time I spent with them. And if I had started this (career) earlier I would have lost all of that. I have no regrets.”

Between ”life experience" and theater training, he said, “I’ve paid my dues,” adding, “Done a lot of things, man.” He draws on “every last bit of it.” Leaving a regular job for the vagaries of acting involved risk. “He never let us know when there was struggle,” said Michael. “As an actor you never know when your next paycheck is coming in. He always sheltered us from that. A lot of friends and family thought he was crazy for going after his dream." John defied conventional wisdom that he must leave Omaha in order to make it in the industry. He stayed rooted here and made it anyway. Judy said she never doubted him or his ‘God-given talent.’"I believed in him. We all have gifts and he obviously had that gift, and when you have a gift you should use it."

John Beasley, Omari Hardwick and Loretta Devine on the set of "Spell."

Beasley waited until things at home were solid before trying to act full-time. “We were going through some ups and downs in our relationship, my wife and I. There were things to work through – and we did. I felt it would be better for me to stay here with my wife and family. It turned out to be the best decision I made. Judy and I have been together for most of our life now.” Judy’s not surprised her boys followed their father as actors, "He's in them, he's a part of them." She views his success and the chances it’s given her to visit him on set in places like South Africa and to rub shoulders with stars at red carpet events as "a blessing," saying, "I thank the Lord all the time."

John made his bones on stage, but is best known for recurring roles in the TV series Everwood, Treme and The Soul Man and supporting roles in the films The Mighty Ducks, Rudy, The Sum of All Fears and Walking Tall II.

Inspired by his father’s fortitude, Michael ignored advice he must leave Atlanta to make it. He’s so successfully booked jobs from there that he’s been dubbed “The King of Hollywood South” by Denzel Washington. Deena books her share of roles, too. The couple are grooming their daughter Micah, who already has credits of her own, to follow their lead. “She’s next,’ Michael said.

“I believed in him. We all have gifts and he obviously had that gift, and when you have a gift you should use it.”

The Beasleys believe in self-empowerment and self-determination. Michael and Deena share on social media their experiences as testimonies and affirmations in order to encourage others. “We put out into the universe what we want and expect to see,” Michael said. “We tell people that if we can do it, you can do it, too. We’re not more special than anybody else. It’s just that we decided this is the journey we want to take and we accept whatever shows up. It may work, it may not work, but we make adjustments along the way.” In a November post, Michael shared: I remember I couldn’t afford to pay the light and gas bill … both being cut off … needing unemployment and food stamps to put food on the table … driving seven hours for just one line in a film or TV project … having to sleep in my car a couple hours to drive back to Atlanta because I couldn’t afford a hotel room … our house being foreclosed because I couldn’t pay the mortgage. I didn’t allow those experiences to stop me from telling MY STORY. I decided not to focus on the obstacles, I ONLY FOCUSED ON MY DREAMS and GOALS. The only thing keeping you from getting what you want is the story you keep telling yourself.”

Throughlines

Keesha Sharp, Kenny Leon (director), Anthony Chisholm, August Wilson (playwright) and John Beasley during the Alliance Theater production of "Jitney" in Atlanta in 1999.

Michael believes his entry into acting was ordained. His father was in rehearsals for Jitney at Atlanta’s Alliance Theatre. Michael stopped by to observe. The rest is history. “One of the actors was late so I sat in and read his lines. I didn’t feel like I did a good job at all. But something hit me about that that made me think maybe I can reinvent myself as this. I studied the patterns of it to see how I can make this work. I got agents in every single state in the southeast.” Auditions and gigs followed. Where he had the advantage of seeing his father carve out an acting career, John didn’t have anyone to show the way. He, Kevyn Morrow and Randy Goodwin became the first African American actors from Nebraska to break through nationally in the early 1990s. Gabrielle Union, Yolonda Ross and Q Smith followed.

Tyrone’s taken a different path tracing some of the same ground his father tread. Just as John broke color barriers getting cast in parts historically filled by whites, Tyrone made diversity, equity and inclusion a major emphasis at The Rose. He intends doing the same at Nebraska Shakespeare, which earlier this year saw actors and staff leave in protest over DEI shortcomings.

In another through line, father and son made their professional acting debuts in Shakespearean plays three decades apart. During John’s Philly exile he acted in a production of As You Like It. Tyrone earned a role in a production of The Merchant of Venice directed by Peter Sellars at his father’s old stomping grounds, the Goodman Theatre. It co-starred Philip Seymour Hoffman and John Ortiz. The prime gig included a European tour.

In London, Tyrone connected with another family legacy when Merchant was performed at the Royal Shakespeare Company. Decades earlier a touring troupe from that noted company came to do workshops at UNO that his father participated in. Encouragement from those stage-trained working actors, including David Suchet, convinced John to stay the course. When Suchet returned as a guest director, he cast Beasley as Mitch in UNO theater mounting of A Streetcar Named Desire.

Just as his father was encouraged to press on, Tyrone found Merchant “an amazing experience for my first professional experience.” Sellars made a lasting impression. “He was the first director I worked with or met who seemed genuinely interested in people. He told me he wouldn’t cast anyone he couldn’t sit down and have dinner with. Every city we went to he would take the cast and crew to dinner. It was a great experience. Working with him helped inform me as a director in making sure I’m caring for the cast and crew as an ensemble and a family.”

Tyrone applied those lessons at his father’s theater, where the entire 10-play cycle by August Wilson was produced, “One of the goals when I opened the theater was to introduce Omaha to August Wilson,” John said, “because he’s such an important part to my whole career. It’s just a rich legacy he's left Black actors and the world for that matter. His stuff crosses all lines. He wrote some roles for middle-aged and older black men I can do the rest of my life.” Wilson’s work resonates with Beasley on many levels, especially its look at Black manhood, frustrated dreams and community hustles. Beasley can identify with many Wilson characters and situations, who recall his own experiences as a father, athlete, entrepreneur and jitney cab driver.

Truth guides Beasley in how he approaches his craft. It’s what drew Wilson and Duvall to him. “Honesty really is the hallmark of what I do. I try to be as honest in my performance as possible to create a believable character.” His theater, which bridged the loss of the Center Stage and Afro Academy of Dramatic Arts, was a training ground for emerging-aspiring actors of color. Father and son led workshops. Alums Kelcey Watson, Andre McGraw, Vincent Alston and Carl Brooks are now enjoying acting careers of their own.

The Beasleys’ local stage work has touched many lives. Some of those connections are multigenerational. For example, Omaha’s TammyRa’ Jackson acted in Beasley Theatre productions and recently both she and her daughter Nadia Jackson appeared in the hip hop Romeo and Juliet Tyrone did for Nebraska Shakespeare. Nadia’s the latest Black actor from Nebraska to pursue a career in New York. At The Rose Tyrone collaborated with national performance artist Daniel Beaty on projects cultivating stories of real area families variously impacted by discrimination and gun violence.

The Beasley Stock Company

With so many Beasleys in the theater arts, they have their own family stock company. For that same Romeo and Juliet show, Tyrone employed nephew Darius Brandenburg as the music director. In this era of Black content being in high demand, the Beasleys hope to do a project that brings all the family’s creatives-artists together. Michael is developing a pilot for a half-hour comedy series based on his family’s rather unique arts-athletics profile and their distinct personalities. He envisions it as a platform for him, Deena, Micah, Darius, Tyrone, his father and other family members to shine in. Even Malik might bring his NBA allure, photogenic looks and acting bloodlines to the project. Everyone in the family’s found their niche. “We’re all on different journeys and paths,” said Tyrone. Deena agrees, saying, “We’re all doing our own thing, but at the same time doing things together.”

“We’re all doing our own thing, but at the same time doing things together.”

Two of John’s nephews, twins Darcell and Darrell Trotter, are the subjects of the 2018 documentary Out of Omaha. Filmmakers followed the lives of the brothers over several years as they negotiated systemic traps threatening to make them victims of society’s mass incarceration complex. Darcell has an interest in acting and music. He was directed by his uncle Tyrone in an Omaha Community Playhouse production of A Raisin in the Sun.

Before theater became his career, Tyrone avoided that inheritance. “I would do things around the house – imitate people and do scenes from movies and that kind of thing. My dad thought I would be really good if I did go on stage, but I was too shy to really even think about doing that. He would try to get me to do stuff for the family in front of a big group. I would be like the WB frog and just kind of clam up when other people were around.”

Instead, Tyrone felt more comfortable mirroring his father’s lesser known talent for drawing. “He’s a great artist, a great drawer, and so I would draw. My artistic interests come from him.” Tyrone earned a studio arts degree from UNO. All the while though, he closely observed his father’s acting method. “We would go to his plays all the time. He would ask me to tell him straight how I thought he did. I would say, ‘At first I felt like you were acting and then as it got on I felt you were that character andI I believed you.’”

Tyrone was nearly 30 before he tried acting, using his father’s model as guide. “There’s a perseverance level I saw growing up with him wanting to do this. I remember he’d be in his room going over lines. He didn’t have a play he was particularly working on, but just honing his craft. That’s something I did as an actor. If I wasn’t in a workshop, then I’d be going over a play – Shakespeare, David Mamet, Tennessee Williams, August Wilson. That, I got from him.”

Intersecting Athletics and the Arts

The family’s parallel athletics through line started with John, who said, “I’m told my father was a really good basketball player, so that’s four generations there. I never knew that side of him. My father was never around. But he taught me a lot by not being around if that makes any sense. He taught me to be the father I didn't have.” Michael confirmed, “Our father taught us how to be men by showing love and always being present and always showing interest and making sacrifices for the family.”

Growing up in North O athletics was a rite of passage and way out. John excelled in football at Tech. He played service ball overseas. It was only when his coach asked where he planned to go to college that he gave serious thought to higher education. The coach contacted then-University of Nebraska head football coach Bob Devaney about him. The Huskers invited him to a tryout in Lincoln through community activists Charlie Washington and Beverly Blackburn, who acted as liaisons for NU with Black recruits. With no reliable means of transportation or accommodation, Beasley declined the offer and instead walked on at Omaha University, showing up unannounced in head football coach Al Caniglia’s office asking for a scholarship. After a tryout, he got one. He played both ways, calling signals as a linebacker and serving as a pulling guard for All-American quarterback Marlin Briscoe.

Beasley came of age when the Black community produced a gallery of star athletes – Marion Hudson, Bob Gibson, Bob Boozer, Roger and Gale Sayers, John Nared, Fred Hare, Ron Boone, Johnny Rodgers – and coaches such as Josh Gibson and Don Benning. In that tight-knit, close-quartered, proving ground he knew many as mentors or friends. As his experience straddles athletics and the arts, he’s in a unique position to chronicle the life and times of Briscoe, who went on to be the NFL’s first Black starting quarterback. He looks to produce a feature film, The Magician, about Briscoe.

Michael made a name for himself in athletics thanks in part to his father becoming a tennis nut. John got the whole family hooked when few Black families participated in the sport. Michael got skilled enough to be one-half of a state title doubles team. He credits the game with developing his footwork for hoops, where his play earned him a scholarship to the University of Texas-San Antonio. His game developed sufficiently to prepare him for a professional basketball career in South America and Latin America. “I was getting paid to do what I love to do,” Michael said. “It was beautiful learning these different cultures, languages and dialects.”

Tyrone still plays tennis. His mother is quite the golfer, often besting John. Competition doesn’t stop at sport, as Scrabble is a serious family pastime, There’s some debate who’s the reigning champ: Michael or his mother Judy.

Michael, Deena, Malik and Micah Beasley at the 2016 NBA Draft.

Malik Beasley has taken his father’s hoop dreams to the next level. The shooting guard became a high school phenom in Atlanta, then a one-and-done star at Florida State, before declaring for the NBA. Drafted by the Denver Nuggets, he played three and a half seasons for that franchise before being traded to the Timberwolves, where he’s trying to regain the form of 2019 and 2020, when he broke through as a starter. Growing pains on and off the court have slowed him down. Only 19 when he got to the NBA, his parents moved to Denver to provide the support they knew he needed in the surreal transition from broke teenager to millionaire. “Sometimes Malik wants what we have, and so he’s in a rush to get it,” Michael said. “I have to explain to him it took years to build into this, and you’ve got to find the right person to do it with as well. People think because these guys have a lot of money they’re mature.” Making millions of dollars at 19, Deena said, “does not equate to knowledge or experience.”

The couple don’t know of other actors with an NBA son or of a family where acting, athletics and the arts run so deep. It’s why Michael’s intent on bringing the Beasley saga to the screen. “We’re definitely going to try to get it done. The family dynamic is pretty unique. I think it’d be interesting to dwell upon that because we have stories upon stories we can talk about.” None of it would be fodder for news or entertainment if John hadn’t taken the leap. “He asked my mother to give him three weeks to try and live his dream,” Michael said. “He booked a job within that time period. Now the rest is history.”

“I always felt God made me a promise that when I was ready, it would be provided for me,” John said. “That’s why when I left UP I knew I had a promise from God that I could do this. I stepped out on faith that doors would open up and sure enough they did. I’ve just been blessed. It’s been quite a ride.”

When the Beasleys gather, acting and the arts are major conversation topics. “We talk about it a lot. It’s part of our lives,” John said. With Broadway looming, he’s looking ahead rather than looking back. “I have no intention of slowing down, so my job is to continue to keep up my health and to be ready when the next opportunity presents itself.”

Indeed, there’s much he still wants to accomplish, such as heading the cast of a film or TV show. He wants to support his family in their endeavors as long as he can. He counts as a blessing their shared creative legacy, sure in the knowledge that when he’s gone, they’ll keep creating in love.