Ira Combs Works to Bring Health and Well-being to North Omaha

by Leo Adam Biga

“Somebody do something!” is the mantra that guides Ira Combs in his work with North Omaha Area Health (NOAH). Community comes first for the veteran registered nurse and healthcare advocate.

Ira Combs

When Ira Combs attended Grace Bible Institute in the early 1970s, he had every intention of being a missionary in a developing nation. But once he did community engagement work with a group of “at-risk” boys in South Omaha, he realized he could be of service, just as well, at home.

“I saw a picture that you don’t really need to go to another country to be a missionary,” he says, “There’s enough work that needs to be done right here.”

In the ensuing years, Combs had fulfilled several vocations, each revolving around serving others. He was a chaplain at Boys Town. He founded-directed a North Omaha foster care facility, Jeremiah Home for Children. Then, he studied to become a paramedic and worked in the profession a few years before determining he wanted to be a nurse. He got his nursing degree at age 40 and proceeded to work as an intensive care, ER, and oncology nurse.

NOAH Clinic Staff

Combs eventually created North Omaha Area Health, a low or no-cost healthcare organization that provides holistic care through its NOAH Clinic. He continues running it today. “Our goal to make North Omaha the healthiest spot in Nebraska is pretty lofty considering right now that North Omaha is one of our state’s sickest areas. We can change that. It doesn’t take a lot of money. But we can change things just by giving people information and offering them free health screenings,” says Combs.

The clinic closed temporarily in March to abide by COVID-19 quarantine precautions. NOAH’s a landing place for information on how to stay safe in this crisis. Combs recommends these basics:

Wash your hands frequently and avoid touching your face

Practice social distancing, but not social isolation; check-in with friends and family

Limit the amount of news you watch daily

Eat healthily

Exercise any way you can, even just walking and taking stairs

He is a humanitarian by nurture and nature.

“My wife calls me a rescuer, a fixer, a helper. She says, ‘You’re just out there trying to save the world.’ It’s true, all the jobs I’ve done involve helping people.”

Health matters are not just professional but deeply personal for Combs. His wife Victoria has been confined to a wheelchair for decades. “She’s kind of my hero. We don’t talk about disabilities – we talk about abilities.” The couple raised three children, Jamita, Caleb, and Antoinette, whom they adopted. Antoinette was born prematurely. She required a liver transplant. Drugs she was administered caused complications that led to heart failure and death at 22.

“[Antoinette] had a very full life and she influenced my work in nursing a lot,” Combs says. As for himself, he’s in Stage 4 renal failure. He undergoes dialysis and awaits a kidney transplant. He still goes to work every day.

Grandparents Anna and Lee Combs

All these health challenges have made him a more empathetic and empathic caregiver. He traces the earliest root of his compassion to something his grandfather Lee Combs used to say. “'If something happened, whether it was a tragedy or a good occasion, his simple words were, ‘We have to do something.’ And my grandfather would do something. He wouldn’t leave it to someone else or the government. That kind of got instilled in me, so when something happens I don’t just step back and watch, I automatically step forward and do something.”

“That’s kind of the whole crux of what I do.”

“‘We have to do something.’”

Growing up, Combs, his siblings and parents would go to Missouri, where his grandparents lived, to help out on the family farm. He saw first-hand, relatives and neighbors working together for a common cause. It made an impression enough, that he led that group of South Omaha boys he worked with in college, to visit nursing homes and to do other community work.

Then there’s the influence of being an Eagle Scout. Earning merit badges and roughing it on camping excursions taught him leadership and self-sufficiency skills that still guide him today.

“It gave you a sense of self—that I can do this. I think that’s the best thing about scouting, even though it’s kind of tarnished now with all this stuff in the news,” he says, referring to a national scandal of sex abuse within scouting ranks.

Combs was among seven Black Eagle Scouts from the same Troop 23. “That has to be some kind of record,” he says. He counts their late scoutmaster, Herman Dryver, as a key mentor in his life. Combs learned work ethic from his parents. His father was a laborer at Wilson Packing Company. His mother, a hairdresser, cafeteria worker, and housecleaner.

The can-do examples of his youth inform the work of NOAH. It fills a niche left by for-profit, big healthcare not having a presence in underserved communities. Combs believes that clinics like it and the people they serve must be the solution themselves.

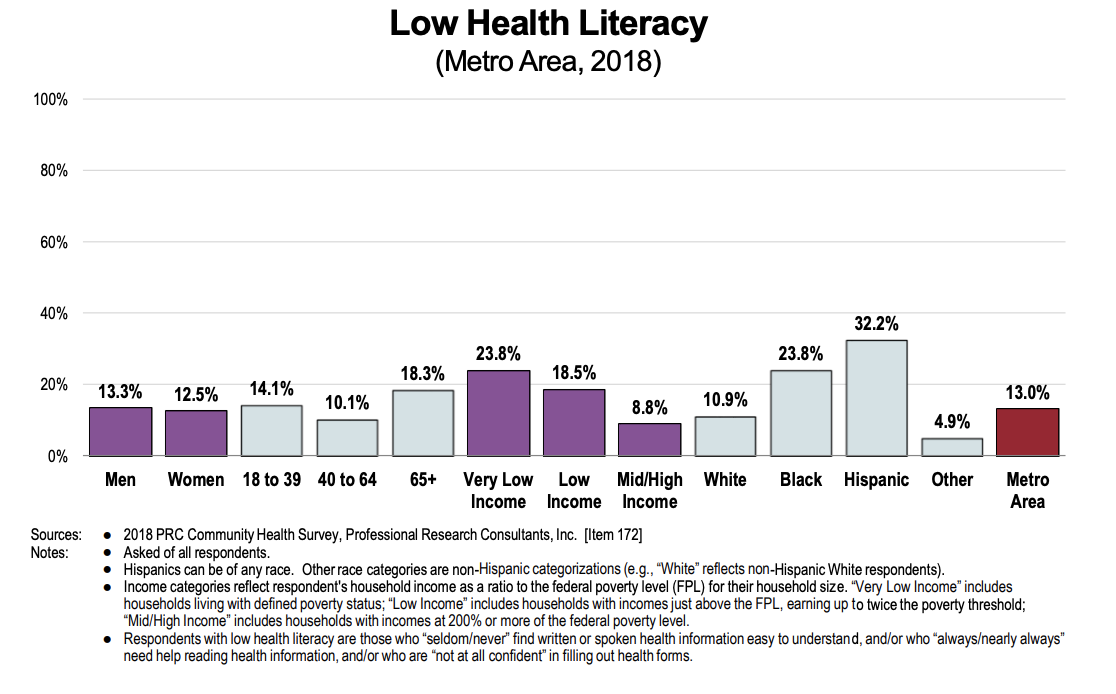

Black and Hispanic populations show the highest of being health “illiterate” or have difficulty within the health care system. 2018 Community Health Needs Assessment Report - Douglas, Sarpy & Cass Counties, Nebraska Pottawattamie County, Iowa

“We can do small things ourselves that make a big difference and it shows. At NOAH when we take blood pressures and blood sugars we find people in the community who have no idea they have hypertension or diabetes. About seven out of a hundred people we check either have malignant hypertension or diabetes. But they don’t know because they have no signs or symptoms,” says Combs.

“Knowing about it and treating it can prolong your life. So these ‘little’ things can make a difference.”

His early experience working in healthcare impressed upon him the “disparities” facing the African-Americans community in northeast Omaha. It’s where the Omaha Central High grad grew up. He joined the civil unrest of the 1960s that expressed dissatisfaction with inequality. He witnessed riots that left only a shell of the North 24th Street business district. More hits followed as packinghouse and railroad jobs disappeared, Black folks fled the city seeking more opportunities, and the 75 North Freeway disrupted neighborhoods and displaced residents. For all the ills of segregation, North O was more cohesive and self-reliant then. At least four private Black doctors practiced there. When they retired, no Black doctors replaced them. Omaha’s acute care hospitals were once all located in the inner city, but they all moved out west. Service gaps resulted.

Combs addressed this lack of resources by using prevention and education to fill the void. His first attempt at bridging the healthcare divide came in the form of an informational newsletter he launched under the name NOAH. Then he began doing blood pressure, diabetes, and STD screenings in a community plagued by the ailments. He added mini-clinics and health fairs. Finally, he opened a permanent clinic of his own under the NOAH banner. It’s located today at 5620 Ames Avenue.

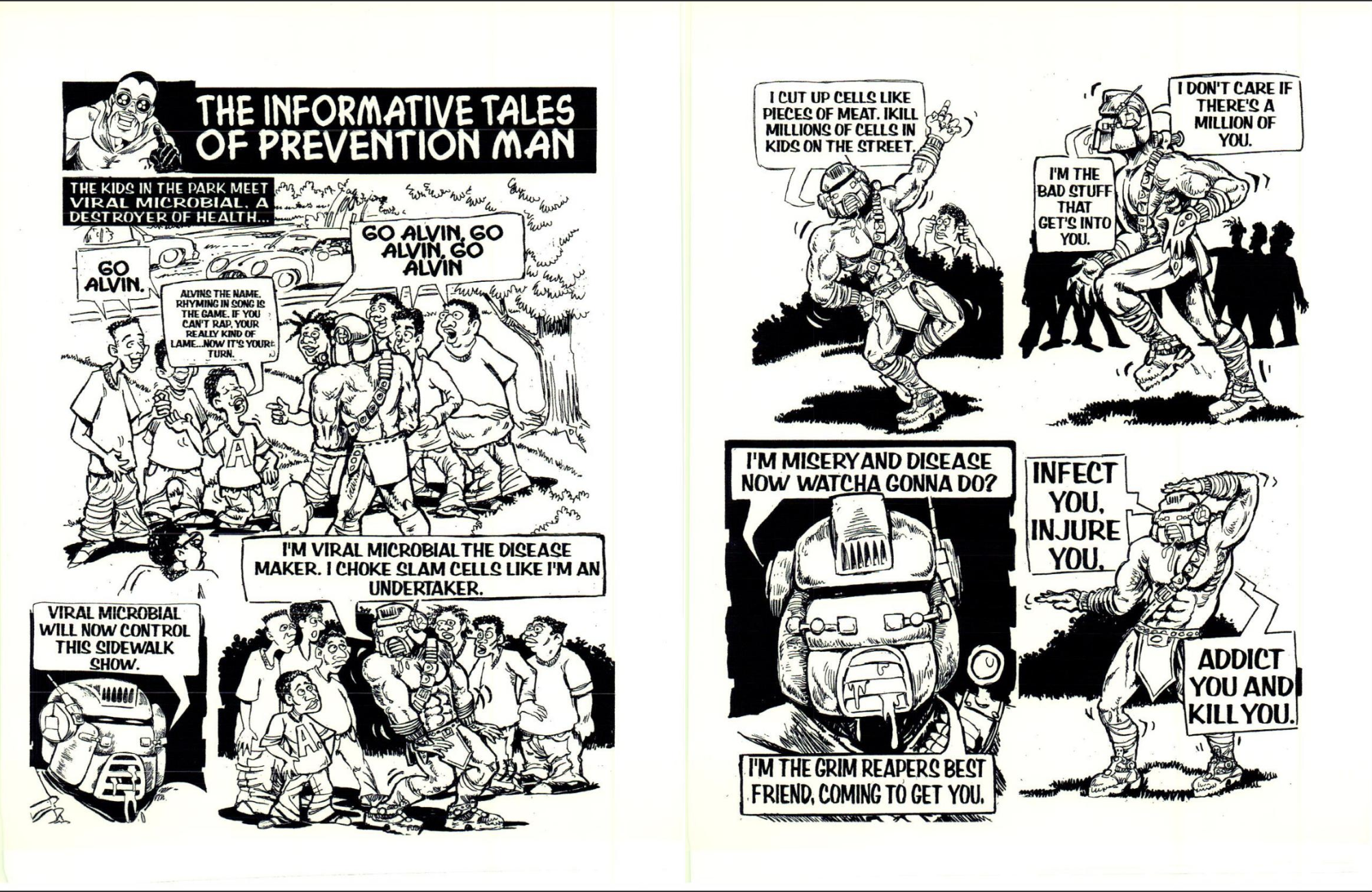

“We started a campaign with kids. We created a mascot called Prevention Man.”

More mascots followed, as did puppets and health topic-themed coloring and comic books. NOAH now has a robust website and social media presence, complete with a podcast.

This evolution played out while he was the Community Liaison Nurse Coordinator in the Center for Reducing Health Disparities at UNMC.

He retired three years ago from the University of Nebraska Medical Center to devote himself full-time to NOAH.

“When we first started everybody was a naysayer. ‘You can’t open a new clinic,’ agencies told us. Things changed when we were asked by Douglas County to do chlamydia and gonorrhea screenings. We did more than anyone expected because we made it convenient and we looked like the people we tested. We had our young staff doing it and they actually live in the community. They go to the same schools and churches and grocery stores as patients,” says Combs.

“Then the State of Nebraska wanted to work with us. We got credibility and agencies starting working with us.”

Charles Drew Health Center became a strong partner. NOAH enjoys many key collaborations. “We’ve made it our mission to do that,” Combs says. Other partners include the Center for Holistic Development, ENCAP (Eastern Nebraska Community Action Partnership), and the University of Nebraska College of Nursing.

NOAH’s staff includes nurse practitioner Mark Darby, director of public health Linda Smith, and several outreach workers. Referring to Darby, who worked with Combs at UNMC, Combs says, “He’s actually taken our services up a notch. He’s also an instructor at the University of Nebraska College of Nursing, which helps us immensely because he brings students for training and that gives us more feet on the ground in giving people help and information. We have a nurse practitioner student who works here once a month. Mark’s also been instrumental in writing grants.

“I’ve been blessed with the talented people working here. We all have a passion to help people.”

Some of his staff have nontraditional backgrounds.

“I will hire a person who has no significant educational or professional background as long as they have a passion to help people, because I can teach how to take blood pressure and blood sugar. I can’t teach how to care for people. That’s something you have to have when you come in.”

Combs has created a multi-dimensional resource.

“We’re not just a clinic. Health is more than just the absence of illness. It’s your overall well-being. A person is not a single problem. A person is a myriad of physical health, mental health, job, family, and we strive to address all those things.”

NOAH staff engages patients to a degree few doctors achieve.

“We train our nurses to give the patient not only the information they need but to build a personal relationship. Some patients don’t want to take meds and we try to explain the benefits versus the problems. We may recommend different meds or alternative treatments. Something a nurse can prescribe is exercise and diet. It can be a really integral part of your health.”

NOAH’s Academy of Healthy Living is a dieting class whose participants, he says, “are losing weight” in a controlled, healthy way. “They meet once a week and support each other. These are the kinds of things we’re doing to improve health conditions .”

A turning point for NOAH came when it received a major three-year grant from the Women’s Fund of Omaha in service of its Adolescent Health Project.

“The goal is to screen, treat, and inform young people ages 14 to 24 to address the STD epidemic. That grant really helped us get up and going, The third year was just up, but they’re going to extend it.”

The clinic receives HRSA (Health Resources & Services Administration) funding through the University of Nebraska College of Nursing.

“We also get reimbursed for HIV tests we do. And we just got certified by Medicare,” Combs notes.

NOAH also depends on donations and an annual fundraiser, though the 2020 event has been canceled due to the quarantine in effect to prevent COVID-19 spread. He’s unsure how NOAH will make up the difference.

Meanwhile, the pandemic’s strain on the healthcare system puts in relief why Combs tries to recruit black healthcare professionals.

“Doctors are a sparse commodity,” he says, “especially doctors that want to work in North Omaha. My concern is that we get young people at an early age interested in healthcare, in medicine, in nursing. You can’t just graduate from high school and say, I want to be a doctor, unless you’ve prepared yourself years before. In order to get into medical school or even in pre-med, you have to have certain training and education.”

About two decades ago he formed Youth Expression of Health (YEOH) as a vehicle for getting young people interested in health careers. Students learn and practice medical assistant skills, interact with health care professionals, and gain real-life insight into various healthcare pathways.

“We do a summer internship program with high school seniors and college freshmen where we give them intensive information and practical experience,” says Combs, adding that interns participate in community health projects and activities.

“We also do a summer workshop camp (at North High).” It’s a week of education and fun that covers traditional and nontraditional health topics from the perspective of diverse experts. “We have some really good success stories of students who’ve gone on to prestigious colleges and universities.”

2019 Youth Expression of Health (YEOH) Cohort

Leadership development is a prime goal of YEOH programs. The information students glean, he says, can impact others in the community when participants pay forward what they’ve learned with others.

“One year we talked about prostate cancer. It was a mixed group of boys and girls. A guest speaker asked why we were talking to girls about prostate cancer, I said because they can take the information to family members or others we would never be able to reach. A month later a girl who attended the camp learned her grandpa was having trouble peeing. She noted it was a sign of prostate cancer. That was enough for grandpa to see the doctor. It turned out it wasn’t cancer but BPH (Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia). The information the girl shared led to her grandfather getting tested and treated.”

In the internship program and the camp, Combs says, “We talk about STDs, safe sex, reproductive education, diet, exercise, smoking cessation, et cetera. We talk about all these things. Our young people are inundated with all kinds of wrong information. We want to make sure we’re getting them the right information and healthy information.”

“The internship is a qualified enrollment partially based on students’ academic record and also on need. We target young people that are high risk. We mentor them up. We have success stories of young men who were in gangs and in trouble in the court system getting their life together,” says Combs.

One of the youngbloods that's transformed his life is Depree Seavers, who counts Combs as a mentor.

“Depree worked our clinics and fairs and since graduating from Metropolitan Community College. He’s now working at UNMC as a paramedic in the ER. He comes back and volunteers with us. He’s a really good influence on some of the young people working here to show them that, yeah, you can do it.”

Another positive role model is Community Outreach specialist Shomari Huggins – one of NOAH’s original summer interns. He runs health awareness programs at various schools and helps facilitate YEOH programs.

Combs hopes to hold the summer internship program and camp this year but is taking a wait-and-see-approach pending COVID-19 developments.

Right to Left: NOAH Inter, Latron "Chrome" Louis, and Shomari Huggins

Job satisfaction for Combs is “patients coming back and telling us ‘you really helped me – my health has changed for the better’,” he says. “You get a good feeling when you do something for somebody. That’s worth it.”

His community service has been widely recognized. In 2013 he was named A Champion of Change by President Barack Obama’s White House, where he accepted the award.

“It affirmed that what I’m doing does mean something,” Combs says. “Even with your best intentions sometimes you wonder is this really helping, and to be recognized, to see more people coming to us, and how we’ve grown really has encouraged me.”

He was honored in 2014 as Nurse of the Year by the Nebraska Action Coalition. In 2017 he was named Heartland Family Service Family Advocate of the Year.

At 68, Combs is still going strong, but he’s thinking ahead to when he can’t do it or isn’t around anymore.

“These last couple years I’ve started to be intentional searching for someone to carry this on, so that If something happens to me then this continues. That’s the goal. We have staff here that if something did happen to me, we would keep going .”

What he’d miss most is “working with patients.” “Probably my biggest gripe is that I do a lot of administrative stuff and I’m seeing fewer patients. But by doing the admin stuff I allow members of our team to see more patients in our community. I can deal with that.”

Visit www.noahclinic.org to schedule an appointment, view upcoming events, volunteer or donate.