Against the Current: Lift Every Voice

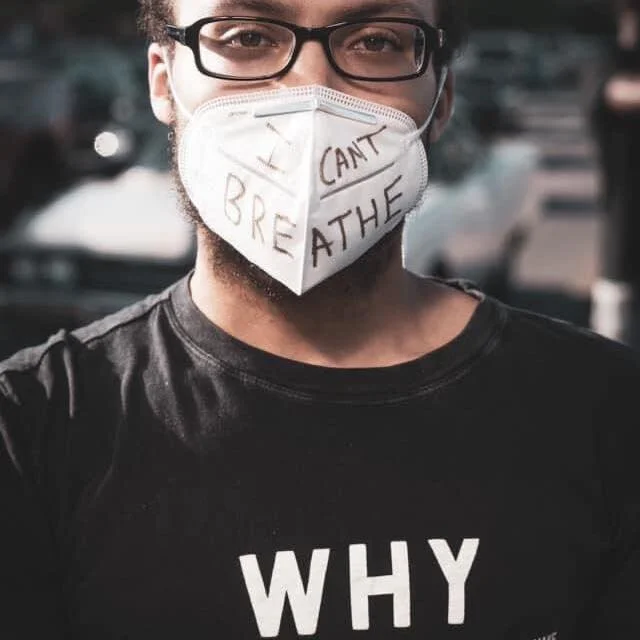

A Protestor puts his hands up on Saturday, May 30/Photo: Andrew Washington

By Leo Adam Biga

Omaha’s rendition of the Call for Justice that echoes across America is composed by diverse figures engaged as activists, advocates, witnesses, and reporters.

Since late May, emotionally-charged protests and unity rallies have called for reform of oppressive systems and institutions. The press for change is playing out on the streets, in legislative chambers, and on social media.

An emboldened Black Lives Matter movement has a broad new following whose philosophical alignment is national, even global, but leadership is hyperlocal.

This fluid movement continues despite shows of force by the establishment in the form of riot police, arrests and curfews, and various threats and assaults by those who oppose the growing mobilization.

Local players on the social justice scene, like State Sen. Ernie Chambers and Dan Goodwin Sr., have fought this fight for six decades. Others, such as Morgann Freeman, have carried the Black Lives Matter banner since 2014. Now, newcomers have recently emerged as strong organizers and civic practitioners.

NOISE spoke with and listened to old and new voices amid this tableau of change for their perspectives and experiences of the struggle.

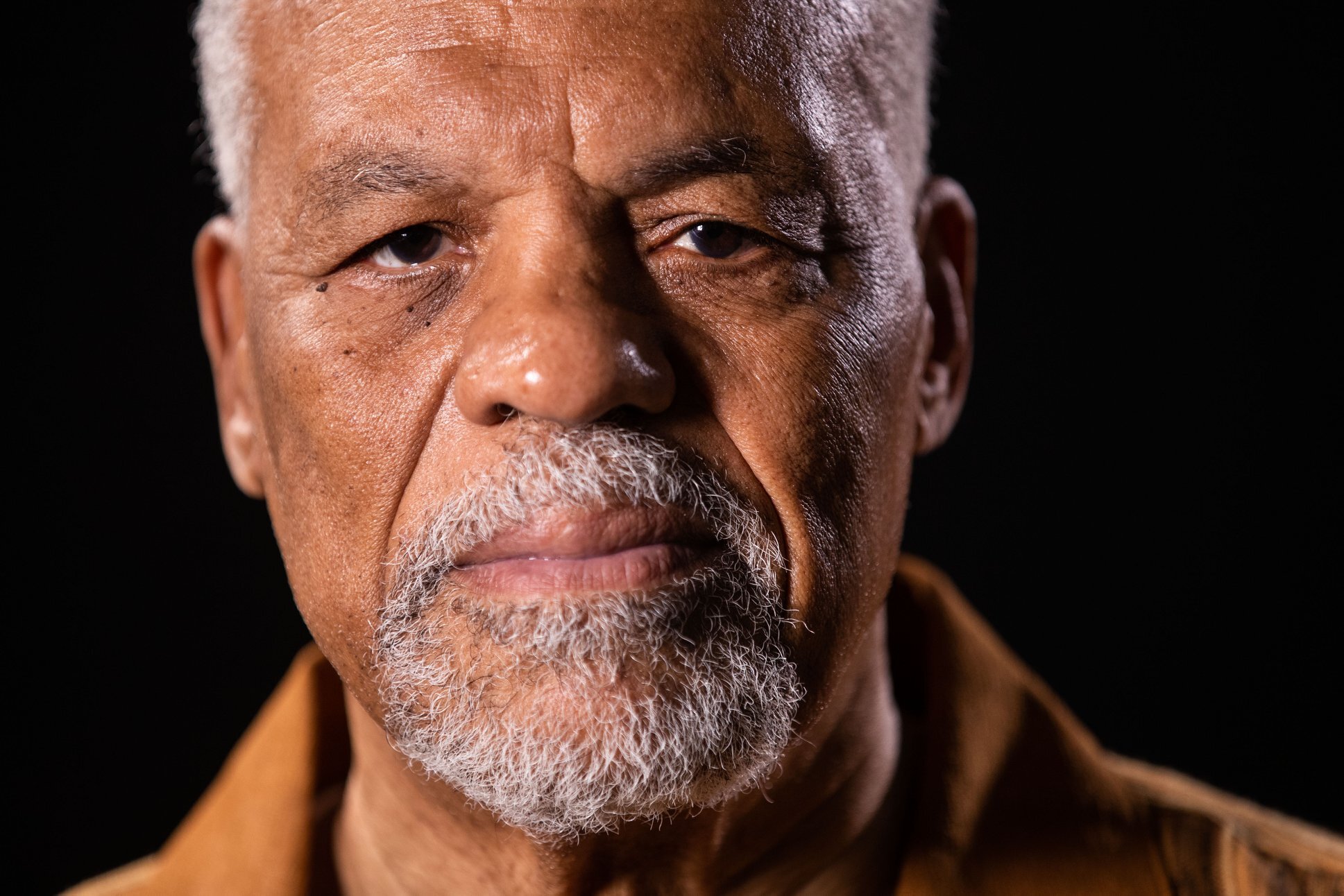

Dan Goodwin Sr./Photo: Lasha Goodwin

Dan Goodwin Sr’s Spencer Street Barbershop has been a hotbed of social-political dialogue since the civil rights era. He attended the 1963 March on Washington and spoke out locally against the same injustices being called out today. He likes the energy behind the current protests. “I’m hoping it will continue. It’s never been like this before. There are some hopeful signs,” Goodwin said.

He’s impressed by how youth are stepping up. “There’s hope there, too. They’re coming up with some different ideas than the older generation.”

Another civil rights era veteran, Preston Love Jr., feels the unrest unfolding today is “having the necessary effect.”

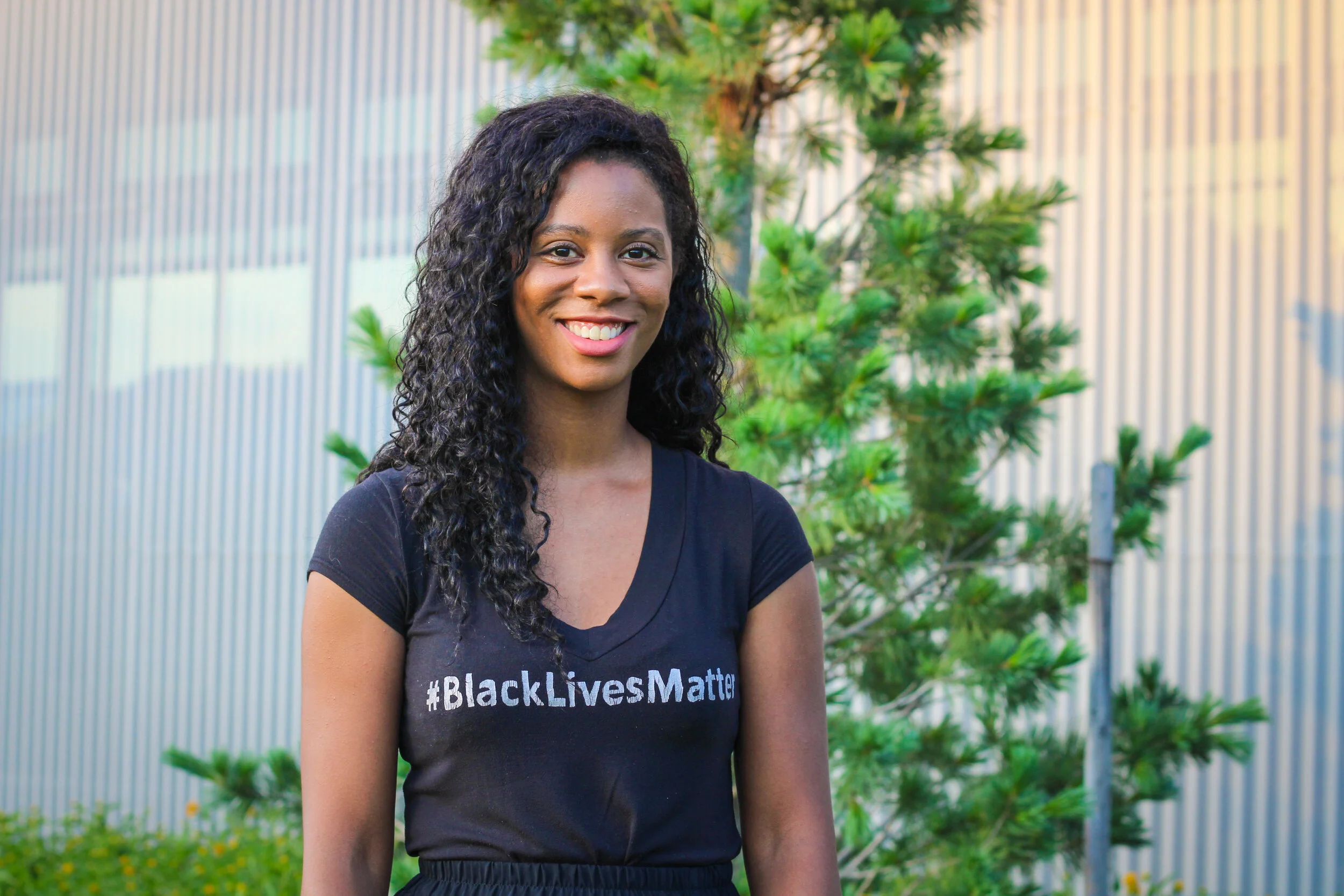

Morgann Freeman/Photo: Lasha Goodwin

“I see myself as an elder and I defer to the energy, intelligence, drive and vision of this movement’s voices,” Love said. “My role as an elder is urging those voices to seek counsel from wisdom. But I say, ‘Go for it.’”

Morgann Freeman immersed herself in the intense swirl of the May 29-31 protests that elicited a heavy police crack down and the killing of protestor James Scurlock by bar owner Jake Gardner. In the emotional aftermath, Freeman posted: “In the past few days I've seen peaceful people get pushed, kicked, gassed and shot. I thought I was going to die when police circled, then gassed and shot families (with pepper balls), after forcing them from public spaces to private property. I saw a young man get murdered in a video in my city. And I see so many community leaders who built their foundation on activism, watch from home, critiquing rather than helping.”

Bri Full/Photo: Lasha Goodwin

University of Nebraska at Omaha public health graduate Bri Full, 24, attended her first Black Lives Matter protest five years ago. Since then she’s also advocated for progressive reproductive health policies before the Nebraska Unicameral and various boards and councils.

“So when Black Lives Matter had its recent resurge,” she said, “I was already familiar with how our local politics work and found myself advocating for change through the Omaha City Council and Nebraska Legislature. I organized the raising of over $2,000 for protesting supplies: water, gatorade, granola bars, hand sanitizer, tear gas deactivation solution, masks, et cetera. With the help of my friends, we disbursed these supplies for the Omaha protests.”

She participated in the June 8th Nebraska Legislature Judiciary Committee listening forum, where she championed policies “to combat racism,” including abolition of the death penalty, ending cash bail, mandatory minimums reform, sensible drug policy, and restoring the right to vote for former inmates.

Full organized an email campaign to the mayor and city prosecutor demanding charges be dropped for all protesters arrested over the Memorial Day weekend in Omaha.

Now she’s leading a team that plans holding July “community building events aimed at elevating the voices of Black candidates running for elected office.” She looks to “connect young people with resources they need to make an impact on our local political systems.” Adds Full, “I think it's really important we elect more Black people into office, get Black people registered to vote, and mobilize them to the polls in November.”

Clarice Dombeck/Photo: Lasha Goodwin

When this movement began, UNO student Clarice Dombeck, 27, felt obliged to act.

“A need to take action is what led me to my activism and civic engagement. My moral and spiritual compass would no longer let me sit idly by, I've spent four years in academia studying social justice and inequality while simultaneously watching injustices take place in my community and around the world for too long. I simply couldn't just watch it any longer,” Dombeck said. “First and foremost I have been learning. I've attended webinars and Zoom meetings hosted by the Movement For Black Lives, Black and Pink, and Black Youth Project 100. I testified at the June 8 [legislative] listening forum. I have participated in numerous protests, including the on-going protest outside Douglas County Attorney Don Kleine’s gated community [that was] facilitated by Culxr House.”

“I am also in the beginning stages of creating a non-profit organization with a small group of my colleagues and peers. Our organization is rooted in intersectional solidarity with a goal to dismantle white supremacy and to abolish every possible form of oppression. As I continue to gain more knowledge throughout this process, our vision and list of demands is changing,” said Dombeck.

Those with something to say employ different means to get their messages heard. University of Iowa historian, Ashley Howard, gives context to this epoch through media interviews and essays. She reminds that the recent wrongful killings of Black citizens sparking this movement are part of a long pattern of brutality.

“The throughline for all those people whose names we know and don’t know is that violence is a very powerful mechanism for social control,” Howard said. “It keeps people in line to do the things dominant society wants them to do – so they don’t forget their place. Think about the ways in which some of the people whose names we know were killed by police officers on duty and others were killed by vigilantes or people who thought they were taking the state’s power in their own hands. It’s a really important thing to note because when people use violence, even if it doesn’t come from somebody wearing a badge, it’s oftentimes condoned by those in power.”

As Dan Goodwin puts it, “This stuff has been happening all the time. It’s just that the cameras started to show it now. The video of George Floyd being killed was more than people could stand and it forced people to come to grips with the reality of the complaints we’ve had ... The whole world saw this. This country should be ashamed. ‘The land of the brave and the home of the free’, and for us it’s the land of the slave and the home of the tree.”

“Lynchings are still going on,” said Goodwin, referring to recent hanging deaths in four states initially ruled suicides but now being investigated as lynchings.

“The other throughline we need to think about,” Howard said, “is that racial violence cannot just be codified as physical interpersonal violence. We also need to think about structural and institutional violence as ways in which the systems, structures, and mechanisms are also designed to keep people on the margins of society, whether Black, Latino, transgender or other marginalized citizens. Those laws are established to make sure they are on the outside and don’t have power.”

Doug Paterson/Photo: Lasha Goodwin

UNO theater professor emeritus, Doug Paterson, a Theatre of the Oppressed champion, referred to the 1968 Kerner Commission report filed after riots raged across America, in a statement he read before the Nebraska judiciary listening session. The report, which concluded “our nation is moving toward two societies, one black, one white – separate and unequal,” warned of the deepening division and pointed to poverty as its main culprit.

Quoting from the report, Paterson told the committee: “Poverty is violence. That’s what this is about. That’s violence. Black people don’t need to be schooled about violence or institutional white supremacy where white people dominate not just the streets, but the schools, the workplace, the banks, the shopping centers and the legislature. It’s in no way a democracy. But it sure is violence, every moment of every day.”

Mission Church ministers Myron Pierce and Ron Smith preach everyone has a part to play in change, which is why they implore churches and citizens to step up and speak out.

“There’s a new message in our city – it is that we are for North Omaha,” Pierce said at a June 3 pastor-led rally. “It’s not just what we’re against, but it’s what we are for. And I want to clarify this – the church is for North Omaha. The church is for you. We know we have not always done a good job. We’ve talked more about what we’re against and less about what we’re for. But we’re going to change, we’re going to make a difference.

“We know there are grave injustices happening in our city, but we know first as a church we have to get it right … The church is taking its rightful place.

From this day forward we make a commitment as pastors and leaders – this is a city of hope.”

At the same rally, Smith challenged the crowd to get involved. “One thing I know about human beings, we get it wrong. But sometimes we can get it right. I’m crying now unless all of us help those who got it wrong, get it right.” Smith said a call for change must resonate from “the pulpit to the White House, to the governor’s mansion to the mayor’s house, to the street.” “It’s happening in the street. Don’t dare lock yourself up behind your wall and closed doors. Get out and be uncomfortable – and lives can be spared.”

Josh Dotzler

Nonprofit leaders like Josh Dotzler, teaching pastor at Bridge Church and CEO of Abide Omaha, leverage social-community capital to try and move beyond rhetoric to action.

“Martin Luther King Jr. spoke to how white leaders felt activists were pushing too fast and hard in bringing change and how when you’re in the middle of the struggle you can’t push fast enough. He said the reality is there has been no change without action,” Dotzler recalled. “The calling for us is we can’t just sit around and talk. We can’t just keep dialoguing. We have to rise to the occasion and take action, we have to see change, and not through violence and destruction. But sometimes you’ve got to take a stand. Peaceful protesting is a powerful way to take a stand for what you believe.

“The dominant culture is the one making the rules. They’ve got the leverage in the relationship. I think the Black community in so many ways doesn’t feel like it has the influence and leverage to make decisions. Whenever somebody else tries making decisions on behalf of your community, while there may be great intentions, it’s not always the right strategy or perspective.”

Dotzler suggests the kind of change needed now is “not just decisions made at the highest levels politically,” “But within organizations, within communities, within individuals,” he said, “we have the power to make intentional decisions that shift the trajectory of our city. So as leaders we have to create a level of awareness. We’ve got to create strategies around long term investment.”

Preston Love Jr. emphasized that lasting social change begins at the polls, which is the focus of his Black Votes Matter organization, recently rebranded as 4Urban.

“There can be quick victories,” Love said, “but some of the really systemic change is long-term. I’m suggesting one of the biggest emphases ought to be on investment. We need to begin to solve poverty, which would begin to solve a whole lot of this so that we’re more self-sufficient. It’s the self-sufficiency I’m worried about.”

“I think we will be able to come together as a community and recommend suggestions we all can agree upon as solutions to some of the issues – police-community relations and aspects of the criminal justice system. The only way for that to really be successful is for it to emerge. If we try to make it work, it won’t.”

Likewise, Love said, the leadership driving home change is “going to emerge – we don’t have the automatic person or organization, absolutely not.”

In the historic civil rights movement, Black churches took the lead. In this more secular era, Black churches don’t carry the same clout. In Omaha, some organizations may be poised to take the lead candidates, but Love feels there’s no one “agreed upon choice.” “It’s not that simple, and even if it were to translate that into an agreed upon action plan would still be hard.”

Consensus in such a diffused environment is tricky.

“We have several dispersed kinds of leaders and leadership,” said Love, “so the question becomes can we mature and consolidate our thinking and become unified transactionally so we can move the agenda forward as a community.”

At the height of the Omaha street protests, activist Peyton Zyla expressed frustration with what he saw as a leadership vacuum: “Where is our community ‘leadership’? Where are our ‘community leaders’ in these dire times? Where are they when our young Black souls are being killed, imprisoned, beaten and systematically oppressed? Community leadership in North Omaha is severely lacking. We don’t have a plan for any of this, we don’t know how to organize our whole community towards the same cause, because our leaders have failed to lead, communicate and speak out. There are too many voices ‘leading’ people in so many directions.”

Morgann Freeman sees Black Lives Matter at the forefront of a new grassroots leadership model. “Locally it’s been a lot of individual people who identify with the movement doing demonstrations and community work around the tenets of the movement. We haven’t had any formalized structure, but we’re starting to see that come together, which is beautiful.”

Mainline civil rights groups Urban League of Nebraska and NAACP, along with the Empowerment Network, work across social, educational, business, political and philanthropic spheres of influence to build bridges for community and economic development.

Meanwhile, organizations as diverse as the Greater Omaha Chamber of Commerce and the Malcolm X Memorial Foundation (MXMF) are being proactive in shows of solidarity and attempts at education. The Chamber organized a statement against racism and a commitment to address racial injustice signed by 150 Omaha-area corporate leaders. MXMF has led marches and hosted forums and is facilitating a Zoom-based anti-racist training program.

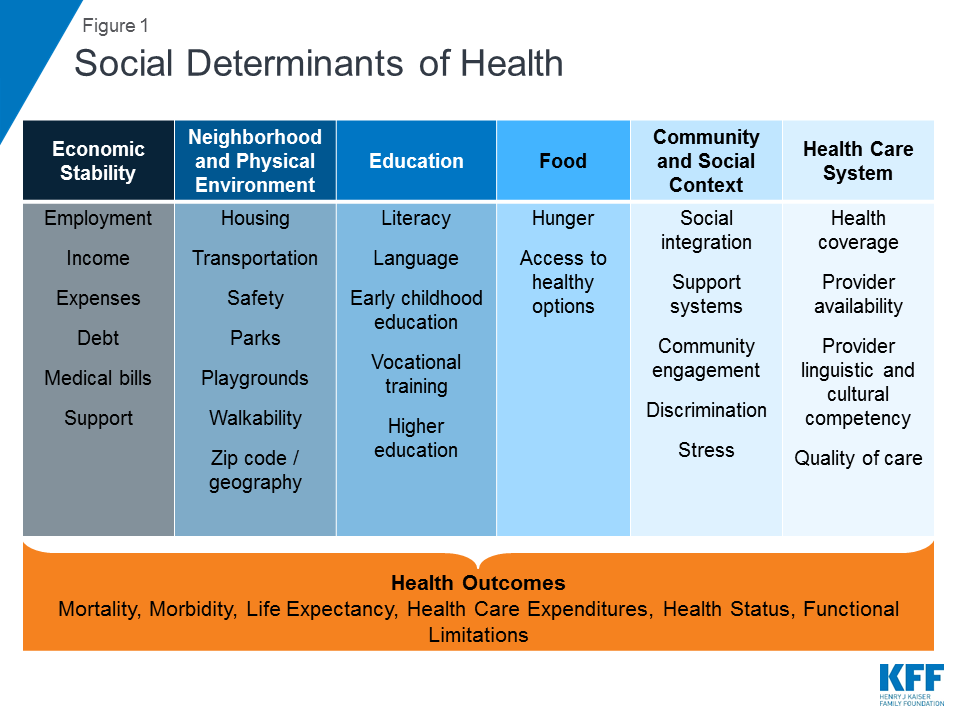

The Douglas County Board of Health recently declared racism a public health crisis. Bri Full applauds the move.

“Racism is very much a public health issue,” she said,” as evidenced by years of credible research,” she said. “According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, the social determinants of health include factors such as socioeconomic status, education, neighborhood, employment, social support networks and access to healthcare. Black communities have been historically ‘redlined’ into poor neighborhoods, which is a direct factor of poor health. Racial bias in the medical field leads to issues like high rates of Black women dying during childbirth compared to white women. Then there’s the chronic buildup of stress Black people experience because of discrimination. Chronic stress can lead to early death from side effects like depression and heart disease.”

At a micro level, artist Marcey Yates has made Culxr House a space for people of all backgrounds to create, express, collaborate. Since May, he’s made it a hub for people wanting to participate as activists.

Marcey Yates, Culxr House/Photo: Lasha Goodwin

“We have the ability to be flexible, which means we can move in what direction is most needed at the time by the community,” Yates said. “We’ve engaged a lot of new people into political civic action in the fight for justice, People who’ve never done it before. People who were scared to stand for something and now they feel like they have people they can stand with to fight the system.”

“There’s been a number of people coming down to volunteer their time to help with operations. We’ve opened our doors for people to come and express themselves by making their own signs and shirts and their own creative expressions,” said Yates.

Artists have created murals across the city honoring James Scurlock’s memory.

Spoken word artist, Mind & Soul host, and social justice critic, Michelle Troxclair is content to leave this new movement to the young people leading it.

“It’s galvanized young people like I haven’t seen in my lifetime,” she said. “I’m very cognizant this is their energy and their movement, so it’s incumbent upon me, even though I’m kind of old hat with this, to be available to them to answer questions. But I am on the support team. I’m letting them be out on the front of this and really craft the message and methodology to achieve the goal.”

“I’m so proud of our young people. They are on top of their game. I’m so heartened to see they are moving this faster than I ever thought possible. I think we have the ear of those in power and we need to seize upon it,” said Troxclair.

A synergy of old and new protest voices gathered at the June 27 “Lift Every Voice, ‘Cause We Got Next” event at the Highlander, which merged “today’s leaders listening to tomorrow’s leaders.”

Peyton Zyla and Lasha Goodwin, are two young leaders who sometimes act as citizen journalists documenting events via videos and images.

Zyla inserted himself with his phone in the crowds demonstrating at 72nd and Dodge and downtown on May 29 and May 30. He live-streamed what happened in real-time. He took a break from posting after he began feeling overwhelmed.

Goodwin has also felt the weight of it all. “As a young person who’s experienced racism and discrimination and is living in this social climate,” Goodwin posted, “I, like others, am exhausted. I couldn’t imagine what someone like my grandfather (Dan Goodwin Sr.) is feeling.”

She understands some folks ”don’t necessarily feel like unpacking all of this subject matter in public, especially when people take our words out of context and only seem to care about what happens to us when we are traumatized.”

“We know there’s been several instances of citizens assaulted or harassed by police. Everyone I know that’s Black, all my friends and family, have this experience,” Morgann Freeman said. “Now we’re all coming forward collectively with our stories. That needs to be investigated and complied with a set of actions taken and repercussions if actions are not taken. We need to work with our state senators to advocate for a study into police brutality and excessive use of force and general police misconduct all across the state, in every level of law enforcement – state troopers to local police departments and everything in between.”

Freeman wants to see investigation of individual cases as well as system-wide patterns of discrimination and abuse of power.

“Moving forward I want to create, among sweeping structural criminal justice reforms, a separate statewide commission to investigate police misconduct. We already have boards or commissions on the state level. This should be one and it should be fully funded. If that means diverting funds from the police, then that’s even better, because they shouldn’t be investigating themselves. They need to be held accountable by an independent party. I think if we had that we would be able to get more justice for people experiencing police brutality and misconduct.”

For Bri Full, meaningful change starts with a defunded police department. As in most U.S. cities, Omaha’s police budget has grown exponentially and crime has gone down. But given historic over-policing of Omaha’s Black community, she feels almost 40 percent of the city’s general fund to cover the cost of “policing” is too much.

“This money needs to be taken away from policing and funneled into better housing programs, mental health services, youth services, education and healthcare,” Full said.

“I'm advocating for the arrest of Jake Gardner for the murder of James Scurlock. Douglas County Attorney Don Kleine needs to resign after his mishandling of the case led to no charges.”

After pressure from many quarters, a grand jury probe of the case is in the works.

Clarice Dombeck wants police resource officers removed from schools, increased community self-governance, universal safe housing and “investments in care over cops.”

Freeman finds hope in so many people choosing not to remain silent but to add their voices to the fray. “I’m pleased this community is coming together to look at how we can intersectionally create change – because that’s so powerful.”

Full takes comfort in the amount of civic engagement happening.

“The most encouraging thing I've seen is people from all walks of life wanting to get involved in making a change in their community for the first time,” Full said. “I think we need to encourage this as much as possible and use the momentum to pressure our officials to make changes that will uplift the Black community and help end racism. If officials will not make the changes we want, we need to use our power to elect new ones who will.

Full concluded, “The most disappointing thing is the lack of urgency and tact I've seen from our elected officials, especially Mayor Stothert. In my opinion, the way she handled imposing the curfew infringed on the community's First Amendment right to protest. There has been next to nothing they've gotten done in regard to reform of the policing system. We need change right now.”