The Black Church in Omaha

A series by Leo Adam Biga

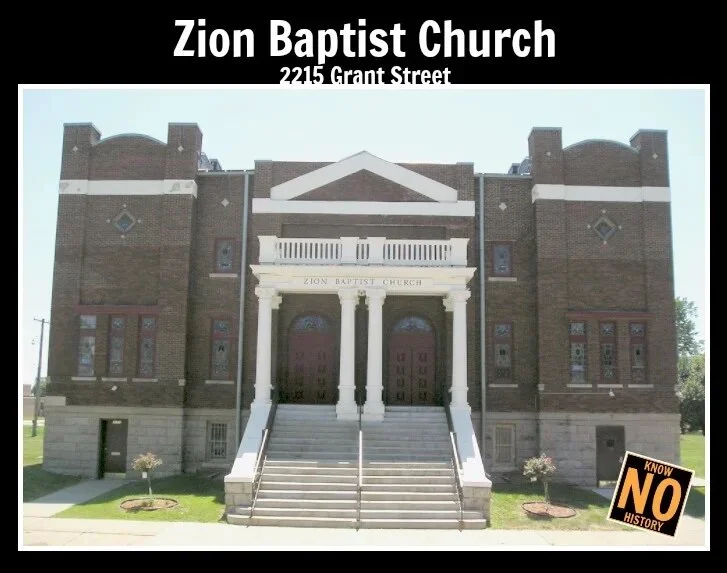

Zion Baptist church

Our church was used as one of the sites for the rallies and meetings.” said lifelong Zion member Gloria Epps “We could hold upwards of 1,200 and those gatherings would fill the lower level, the balcony, and the overflow. There would be a series of presentations to present the problem and then the leadership said, ‘Okay, this is what we’re going to do, we need your support.’ ”

Introduction: How the Black Church Endures

Organized religion’s mainline denominations have steadily lost membership for half-a-century. Gallup reports that for the first time since it began tracking faith affiliation trends in 1940, less than half (47%) of Americans say they have a “formal relationship with a specific house of worship.” But one demographic in the United States, African Americans, holds fast to religion in numbers that used to apply across the general population. When measured by race, the Pew Research Center study indicates that 59% of Non-Hispanic Black respondents remain rooted in organized religion and in churches-- more than any other group.

Based on survey responses to various indices, ranging from the importance of religion in one’s life to attendance at religious services to frequency of prayer and reading of scripture to belief in heaven and hell, Black citizens lead the way, often by substantial margins. All of which, historians and scholars say, confirms the historical importance of religion and church in the life of African Americans, who from slavery through Reconstruction and beyond have looked to it as a source of strength and renewal and a haven against bias and hate. Not to mention a gateway to opportunity.

The vast majority (79 percent) of African Americans identify as Christian, most (71 percent) affiliating with one of the historically Protestant denominations, including Baptist. But even for many African Americans, church holds a less prominent space in their lives today. Before the Covid-19 pandemic, Black churches saw their own drop off in membership and attendance in the fragmentation of families, complexity of schedules and accelerated pace of life. The pandemic posed one more impediment for churches.

Rev. Kenneth Allen, a preacher’s son and now pastor of one of Omaha’s oldest Black churches, Zion Baptist, has been attending church all his life. Since 2008 he’s led the very church he grew up in and that his late father, Rev. James Sterling Allen, pastored in the 1970s.

Zion does not command the membership or attendance it once did, which Allen and others concede as simply a fact of life now compared to back in the day, when church was a taken-for-granted mainstay in people’s lives.

“I think in my father’s day the church touched every aspect of life in the community,” Allen said. “So many more people went to church and were involved in church, and as a result the church had tremendous influence and power. There are now young people who have grown up without the church in their lives, and that was rarely the case in my day. Ironically. it creates more opportunities for evangelism and outreach.”

The situation the church has arrived at reminds him of a scripture passage (Matthew 9:37) that goes: “The harvest is plentiful, but the laborers are few.” “That’s the position we’re in today,” said Allen, “The potential for the saving of souls is incredible.”

Installment II

Zion Baptist Church

Where Everybody is Somebody

- 133 years strong -

by Leo Adam Biga

In the annals of Omaha Black churches, Zion Baptist at 2213 Grant St. stands tall for a resilient history dating back to the late 19th century (Dates of its origin range from 1884 to 1888, but the church goes by 1888.)True to the promised land of its name, Zion’s been at the epicenter in the struggle for Black self-determination and equality in Omaha. The local NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People) chapter often met there. The congregation’s fortitude was tested when the 1913 Easter Sunday tornado decimated the original church building. Through prayers and donations, they erected a new brick church home. During the infamous 1919 Red Summer, Zion facilitated forums about the anti-Black hate crimes occurring across the nation.

1915 architectural drawing of Zion Baptist Church by Clarence Wigington From The Omaha Monitor.

In late September that year, Will Brown was lynched outside Omaha’s city hall. Zion provided refuge to Black residents after that terrible tragedy. Over time Zion welcomed such 20th-century Black leaders as Boston Guardian editor William Monroe Trotter, Urban League of Nebraska executive director Whitney Young (who became national Urban League head), and NAACP legend Roy Wilkins.

One of Zion’s most outspoken pastors, Rev. Rudolph McNair, co-founded the 4CL (Citizens Coordinating Committee for Civil Liberties) in the early 1960s. He was its public face and articulate spokesman. The Zion congregation and greater Omaha Black community followed his lead, said veteran member and Sunday School teacher Darlene Webster, age 86. “Mostly all of us supported him, like when they marched and did sit-ins, [because] we were looking for better treatment.” Lifelong member Gloria Epps and her sisters got arrested with others for protesting during a 4CL action led by McNair. “He was very fervent about what he believed,” Epps said. “He was respected. He provided the vocal leadership as well as the spiritual leadership that group needed in order to step forward.”

Christopher McCroy, a 20-something associate minister at Zion, draws inspiration from church elders who fought for civil rights decades before he was born. He refers to Epps and current Zion pastor Rev. Kenneth Allen as “two giants” who embody “the stories of perseverance that have come through the hallways and the sanctuary.”

Image credit: Adam Fletcher Sasse of North Omaha History

A Zion icon, Dorothy Eure, was a civil rights activist and social justice advocate who stirred “good trouble” from the 1940s up until her death in 1993. As a teenager she organized petitions for the Omaha Public Schools to hire more Black educators. She later participated in Omaha’s two main civil rights action groups, the De Porres Club, and its successor, the 4CL. She often brought her young sons to demonstrations. As the state’s first Black paralegal she represented countless Legal Aid Society clients seeking justice in employment and housing disputes. Her work exposing the unequal education offered Black youth informed the lawsuit a group of Omaha mothers brought against OPS that resulted in court-ordered busing to desegregate its schools.

“She was a warrior,” said Allen, who knew her and her family when his late father pastored Zion from 1971 to 1978. “She was a strong, outspoken activist right there in the middle of it all.”

Eure was also a creative who acted in early Black gospel films and, with her sons, formed the Afro Academy of Dramatic Arts in North Omaha. “She and her family were very strong in the church and very strong in the community,” Allen said. “Mrs. Eure was a legend. And her sons all did a lot, especially in the arts and in community activism, merging those two in a unique way.”

Pulling from the past to impact now

Examples like the Eures drive McCroy to do his part. “It’s a great calling for me to continue to stay not only spiritually engaged but socially, politically engaged. And to make sure the church is forever a cornerstone in those types of conversations.” He admires, too, the grit and loyalty of a congregation that pooled resources to rebuild after the 1913 cyclone and for a century now has mobilized to fight Jim Crow. That backboned legacy affirms for McCroy the practical mission a Black church can fulfill: “There are so many different realms and spheres of society the church is responsible for.”

Photo provided by Zion Baptist Church

Voter registration and its opposite, voter suppression, along with inequitable education, healthcare, housing, poverty and police misconduct, are among issues the church must address, say Zion’s good shepherds and followers. Christians need only look at the example of Jesus to understand religion does have a place in the social maelstrom. “Jesus was not only a spiritual leader but a political figure,” McCroy said. “He caused a lot of political unrest in his time, and I think that is emblematic of the history of the church. When I look at Zion, it’s a continual calling to address, help, aid and uplift the whole person and whole community. The church has been a cornerstone in that work for more than a century. That’s what it means to me every time I step through the doors of Zion.”

Its ranks have included other doers: Edmae Swain, the first Black principal of an OPS school; Robert and Edwardene Armstrong, a former Omaha Housing Authority director and career educator, respectively; Leon Evans, the first Black president of a Nebraska bank; former Nebraska state senator Edward Danner; and one-time Omaha School Board member Robert Myers. A 1965 Ebony Magazine article cited Danner and Myers among the near record number of African Americans elected to public office that year across the U.S. in the aftermath of voting rights and other civil rights laws enacted then. Epps said the congregation celebrated fellow brothers and sisters who represented. “These were leaders within the community and by the way they belonged to Zion Baptist Church.” That sense of ownership and support continues today.

The new Zion that rose from the rubble was designed by a notable in his own right – Omaha native Black architect Clarence “Cap” Wigington. The prodigy graduated Omaha Central at 15 and worked for the renowned Nebraska architect Thomas Kimball. After designing Zion and St. John’s AME Church, he left Omaha for St. Paul, Minn. to become that city’s municipal architect.

“I’m proud we have a body of tradition that’s a part of our congregation…

It makes for a wonderful legacy. Our challenge is not to just rely on our achievements of the past but to keep making new accomplishments for the future.”

Leaning into the church’s legacy Allen says, “I think the advantage to having an older congregation is that we are surrounded by a great cloud of witnesses in the stands, so to speak, cheering us on. We’ve had quite a few pioneers who have been members of Zion down through the years. Quite a few who blazed trails in the city. We have that as a kind of undergirding for all that we do.”

Where Everybody is Somebody

Photo provided by Zion Baptist Church

For all its pedigree, Webster said Zion doesn’t distinguish between rank or class. “It’s a loving, caring, respecting congregation. Our theme is we are the church where everybody is somebody, and Christ is all. We pride ourselves as the Zion Baptist Church family.” She values lessons learned there. “It taught me how to love, accept and respect people, whether I agree with them or not. It taught me what salvation means. I didn’t always know salvation applied to me. I thought it might apply to others, but I learned it applied to me also.”

Zion’s been her rock. “In times of sorrow I’ve been accepted and no questions were asked of me. I felt at ease being here. For joy, it’s been with me for the births of my grandchildren, our baptisms, graduations, weddings, whatever’s gone on.” In celebration and trauma, she said, the congregation has been a constant. “They were there for me through it all. I’ve always been treated with the greatest of respect.”

Epps appreciates Zion’s accepting nature. “It’s not going to change if you don’t dress right or if you say the wrong thing or if your acquaintance some might not approve of. We still love you. As a matter of fact, the people who love you are the ones who will sit down with you in that intimacy and say, ‘I love you, and maybe you need to think twice about this’ or ‘maybe there are options you haven’t thought of.’ We take time and show love by giving the support you need, even correcting you. There have been ladies who’ve cornered me in the vestibule of the church to check me on things. It takes some love for someone to do that. They could just let you go on and make mistakes.”

Webster and Allen don’t agree with Zion’s reputation as “a silk-stocking” church, noting that it welcomes all regardless of social station. “Zion’s always had a mixture of backgrounds. Strong contingents of working class, middle class and upper middle class members,’ he said. “I like it that way. I like being diverse, I like the mixture of people from different walks of life. I think it’s important for the church to be able to go uptown and downtown, and I think that’s where Zion is.”

Community Connections

More than a worship space, Zion’s a vital hub intersecting the world around it. It works proactively in trying to reverse disparities among African Americans in partnership with Creighton University’s Center for Promoting Health and Health Equality. Zion responds to the metro’s STD epidemic, McCroy said, “by not just talking about sex education, awareness and abstinence but really giving high school and middle school students the information they need to protect themselves.” “It seems churches take a hands-off approach,” he added, “but Zion has been very engaged to provide information and education to make sure young people are healthy and practicing safe sex.”

Church program from Zion Baptist 1966 in Omaha , Nebraska. Image credit: The Great Plains Black History Museum

The responsibility that comes with serving a congregation, neighborhood and community, McCroy said, extends beyond “the four walls of the church.” Zion’s long made education a priority. It ran a robust after-school tutoring program. “We were loaded with students,” said Epps, who taught for 31 years in OPS. “Now they didn’t always want to be there, but we had over 90 percent increase their grades, efficiency and skill levels. We even did some ESL work when there was a need for that. We address the needs we see or that open up to us. We’ve always been fortunate to have leadership research where the itch is that needs to be scratched and then address those needs. That’s part of what we feel like we should be doing as a spiritual community. Yes, you preach about Jesus, but then you do for others what Jesus did.”

The Pastor’s Honor Roll champions academic excellence and perfect attendance among Zion’s school-age youth. Every college-bound graduating high school senior from Zion receives a church-sponsored scholarship. “If there are needs further down the road,” Allen said, “quite often we will provide assistance at those times. ”

Meeting basic living needs is part of Zion’s social committment . Neighbors facing food insecurity, Epps said, “can come in and pick up meals during the week.” The church also helps with utility emergencies. “A person who’s hungry or behind in paying their bills,” she said, “can’t always hear you talk about salvation until you feed them or get their lights back on.” Zion hosts both an annual dinner and a yearly cookout for residents of homeless shelters St. Francis House and Lydia House. These events, Allen said, represent “some of the village kinds of things that we do.”

Full Circle

As one of Omaha’s oldest continuously active houses of worship, Zion’s been home to many “saints” who’ve carried its compassionate care message. Among them were Allen’s father, Rev. James Sterling Allen, whose beloved legacy as Zion’s pastor is never far from his mind. The elder Allen was known as “a powerbroker,” he said, who helped Democrats Ed Zorinski and John Cavanaugh win elected office, and chaired the city’s Human Relations board.

Women of Zion Baptist Church celebrating Women’s Day, Men in Kitchen – Men of Zion preparing for the Wiley Philips Wild Game Feast – still celebrated today photo credit: Eleanor Brown

“He was very active in the Urban League and NAACP and with getting OOIC (Omaha Opportunities Industrialization Center) off the ground and building their new facility. He was just a real difference-maker.”

The younger Allen and his siblings grew up in Zion’s warm embrace. “I cannot tell you how much the support, the love, the encouragement of the members of Zion meant to me because even though I had a wonderful experience at Central High School, I dealt with some racism – some people trying to prevent me from achieving. But I had so much support, I refused to fail or give up.”

Allen was ordained and licensed by his father in Philadelphia, Pa., where his parents moved. “It was one of the most memorable times in my life.”

After serving churches in various states, he accepted the call to follow his father’s footsteps at Zion in 2008. He always wanted to return to Omaha, but ministering was not the route he originally expected to take him back.

“After I graduated from the University of Texas and did my graduate work at Georgetown, I planned to come back to Omaha and run for Congress. I wanted to give back to the community that had nurtured me, that had meant so much to me. Of course, God had something to say about that and redirected my steps. And here I am today.”

Allen is married with two grown children.

When he interviewed for the Zion job, he let the leadership know his special heart for it. “I said, ‘Whoever you hire as pastor will have to fall in love with the people and the people will have to fall in love with him, and with me the love is already there,’ That’s the way I’ve always felt. Coming in as pastor, I had a very significant advantage in that I knew many members of the congregation. It’s been a great love affair.”

Coming home meant renewing old friendships. “I’ve been privileged to serve as pastor for some of my junior high and high school classmates who were there when my father was pastor. We used to play softball and card games together, go bowling, get pizza, go to choir and usher rehearsal. We were together all the time.”

Darlene Webster remembers him well. “I’ve known him since he was a young boy. He was with my children in school.” Webster fondly recalls his father. “The young people here loved him. They would follow him to the ends of the earth.” Like his father, she said, the son “has a pastor’s heart.” ”That’s everything for me. It’s a very hard and lonely job. Not everybody’s going to be satisfied with you. You’re wounded by some of the things people do and say. It’s like being a parent.”

Allen returned to a different Omaha than the one he left three decades before. The city limits and population grew but its inner city decayed. Gang violence was a problem. Although strides have been made reviving northeast Omaha and curbing gang activity, he still had to preside over the 2017 funeral of Kayviaun Nelson, whose father is Zion associate minister Charles Nelson. The mother of two was shot in a parking lot and died later of her wounds. Her mother was murdered a decade earlier. On the fourth anniversary of Kayviaun’s death in April, an emotional Nelson delivered the sermon at Zion.

Say Amen Somebody

Like his father before him, Allen doesn’t shy away from the tumult - In or out of the pulpit.

“My father always talked about social justice issues, politics. I do the same. I don’t think I do it as well as he did. He was quite prolific and profound in framing the social dimensions of every problem and of the gospel.”

Photo provided by Zion Baptist Church

Allen proclaims Black Lives Matter as “a great movement.” “It has really done our nation some good for people to rise up and make that statement. When they first started I used to hear naysayers – ‘Well, white lives matter and all lives matter.’ I don’t hear that anymore because people get it now. If you’re going to talk about the gospel and Jesus Christ you have to talk about George Floyd, Michael Brown, Breonna Taylor, Sandra Bland, the list just [goes] on and on. It has been a tremendous asset for this country to have to confront the needless taking of Black life.”

This movement, he acknowledges, “is very different from the civil rights movement of the 1950s and ‘60s, which was much more targeted and strategic.” “Black Lives Matter has been more amorphous and harder to define which is certainly not all bad. But certainly very different than when Martin Luther King Jr. led the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.”

Allen sometimes joins other ministers and community leaders in public statements that take stands on issues, an outgrowth of interracial and inter-church dialogues. He believes in the power of leveraging position and purpose to sway elected officials and policymakers.

Allen believes the Black church’s time to lead on a macro level will come again when conditions are right. “The Black church thus far has not been in the forefront of this latest movement, certainly not in the way it was in the 1950s and the 1960s But even that happened organically. That was not an intentional, orchestrated series of events. It sprang up out of the recognition of a need for something to be done. I think the church will be the birthplace for the true new civil rights movement when it happens,” he said.

Allen doesn’t believe the type of movement he is talking about has happened yet saying, “Black Lives Matter has very little structure to it. It’s been very diffused. I think what the church brought to the civil rights movement is what it will and can bring to today’s movement – that sense of order and structure.” Allen feels the alignment for a reawakening is close at hand. “Conditions are beginning to come together that will allow the church to assert itself and to be appreciated for what the church has to offer.”

Christopher McCroy agrees the church is obliged to respond to issues. “For me, it’s a constant calling to uphold tradition that the church is there for much more than just the spiritual development. There’s a calling to be socially engaged in movements that take place all over the country.”

For church to be a conscience and catalyst for change, then it needs disciples to deliver the word. McCroy is an example of a homegrown prophet raised up in church who received the call to preach as a teen. The fact that Zion still produces a McCroy, a North High grad who went on to Morehouse College and UCLA, is “a very hopeful sign” to Allen.” We’re excited about what doors God has opened for him, the hard work he’s done and the support he’s had from his strong, committed family. He always loved the Lord and the church. It’s been amazing to watch him grow up from adolescence into adulthood.”

Zion works hard to retain young adults through singles and couples ministries.

The church’s positive model has helped McCroy avoid getting caught up in negative urban traps – a reminder church remains a relevant, powerful guide. He’s worked in several education spaces, including the Center for Holistic Development in Omaha, the Uncommon summer academy in Newark, N.J., and the South Central Youth Empowered thru Action program in Los Angeles.

“He is well on his way and we are right behind him one hundred percent,” said Allen. “We want him to be superintendent of Omaha Public Schools one day. We’ve had other preachers as well who have grown up in the church. In fact, Christopher’s first cousin, Andrew Finch, started preaching under me a few years before Christopher did, and now he’s pastor of a United Methodist church in Kansas. A very talented young man. I hated to lose him.”

1923 1st Prize winner with artistic decorations at Zion Baptist Church. Image credit: The Great Plains Black History Museum

Losing human or financial resources is something churches can ill afford today with membership and participation ever waning, though the Black Church is holding its own. How is Zion doing? According to Allen, “Some people reduce it to what we call the ABCs – attendance, buildings and cash. We don’t measure the health of our congregation by those metrics, though they are interesting and even helpful.” Allen gauges his church’s health “by the quality of the fellowship, the level of participation and what difference we’re making in the community, and I think by those standards Zion is strong, and we’re working on getting stronger. Wherever you see something going on meaningful in the Black community, you’ll find a member of Zion active in that effort, whether the Empowerment Network, the Interdenominational Ministerial Alliance (which he once headed), Black Lives Matter,OTOC (Omaha Together One Community), or One Hundred Black Men.

“We formed the North Omaha Optimist Club and we’re working to partner on a food distribution program where people will be able to stop by for fresh fruit, vegetables and other food items provided by the USDA. We work with a program at Christmas-time to provide a party and gifts for children whose parents are incarcerated and we do follow up with those families. We’re not the largest Black church, not the largest Black Baptist church by any means, but we are one of the most active and one of the most faithful ”

Revival is part of Baptist church tradition. It goes with the denomination’s call-and-response affirmations. Allen’s chaired a citywide revival for a Baptist conference of pastors and ministers. He’s put his advanced training to use as a National Baptist Congress of Christian Education faculty member and as a UNO adjunct instructor of Theology and Religion in Black America.

Back in the Fold

Life at Zion, as with any church, hasn’t been the same since COVID-19 protocols first went into effect in 2020. Curtailment of in-person worship dealt “a heavy blow,” Allen said. “I realized for the first time in my life I participated in an Easter Sunday when the sanctuary wasn’t full,” McCroy said. ”It hit me like a ton of bricks. I’ll never forget. Hopefully, it’s the only time an Easter will not be as I’ve known it to be. Missing these elements that are staples in our tradition has truly been a barrier, a hindrance.” Allen confirms COVID stripped away “the opportunity to be together as a church family, the intimacy, the fellowship, the community, going to Sunday school and morning worship, seeing familiar faces, getting those supportive hugs and handshakes.”

Honor student certificate from Zion Baptist Church in Omaha Nebraska. Image credit: The Great Plains Black History Museum

However, Allen said, the new reality “provided an opportunity to extend our reach with viewers who watch our streaming service from several states we would not otherwise touch.” He added, “We use Facebook Live. We’re trying to expand that to include YouTube and stream directly from our church website. Some people who join us from out of state are former members who moved to other places. Some are part of my extended family. But they’re also people we don’t know who stumbled onto us and tuned us in.”

McCroy is pleased Zion hasn’t let the pandemic stifle its spirit for compassionate charity. “We stumble and continue to pick back up and find different ways we can address community needs. We haven’t faltered. We just had to reframe and remold. The message is still the same, the love is still the same, but the avenues in which we express it have definitely been altered.”

“Ironically,” Allen said, “the technology has been there for years, but we didn’t use it. We didn’t think we needed it. But now we recognize we have to use it in order to stay in touch.”

After 14 months of remote services, Zion resumed in-person worship and fellowship on May 1. It marked a real Hallelujah moment. “The idea that we can come together is exciting,” Allen said in anticipation. “We’re going to have a great time in the Lord. We know the majority of our membership probably will not return that Sunday. It will be a slow building process. People have even identified dates they will return. We’re going with those who are ready to go and let others come as they choose to.” When that church reunion day finally came, Allen said it proved an “emotional” homecoming.

Churched Up

Whether as witnesses, evangelists, penitents or servants, people engage with church for more than prayer. It’s where they go to celebrate, to socialize, to serve. Churches depend on volunteers to fulfill various ministries where they can apply a pre-existing skill or develop a new skill that’s transferable. Darlene Webster applied her nurse’s aid expertise as a member of the church’s Nurses Unit. She’s used real world office skills as Zion’s assistant clerk since 1987. Her service, she said, “has been my pleasure.”

Gloria Epps, Zion’s longtime Christian education director, started teaching Sunday school at 13. “I was already the secretary. I learned how to do reports, I practiced math, I learned to research, organize and present information. So many of those skills I was able to use in my teaching career.” The church sent Epps to national and state Baptist conferences and she became a writer for the Sunday School Publishing Board, served as vice-chair of the National Christian Education Committee and as an instructor for the National Baptist Congress of Christian Education.

“That formative leadership has its root in Zion Baptist Church,” said Epps, a UNO adjunct professor of religious studies. “That foundation was made at Zion and it’s still being laid as a matter of fact.”

Zion Baptist Church circa 1918. Image credit: The Great Plains Black History Museum

“Zion was foundational in every aspect of my life,” McCroy said. “It presented the first opportunity to use my voice and focus in on some of my passions. Anything I wanted to do, the first place I got the opportunity to do that was the church. If there was a skill I wanted to develop, it started in the church. For me it was one of the only places that combined my family, friends and community, so the church for me has always been this gathering place. There was always somebody willing to develop and initiate that intellectual curiosity. If it wasn’t for my pastor exposing me to what Historically Black Colleges are, I wouldn’t have went to the college I went to. If it wasn’t for individuals like Dr. Epps, I would never have become a Sunday School teacher.”

Likewise, Allen basked in the familial warmth of a congregation celebrating his success. “I was the first African American to win a state championship in debate in Nebraska. Coming back from the event I asked to borrow the trophy overnight. I asked to be dropped off at church because I knew choir rehearsal was going on that evening for the choir I was a part of. When I came into the sanctuary with the trophy held above my head the whole choir broke out in a spontaneous standing ovation. It’s that kind of support I got from Zion.,” Allen said. “When I left for the University of Texas, I felt unconquerable. I felt I had all I needed to succeed, not just because of the education I had received in the school system but because of the support I had received from Zion.

“Sister Epps grew up in Zion and was an achiever. Has been an achiever all her life. Along with her sisters. They excelled in school, graduating with honors, and in their professional lives. Minister McCroy graduated with honors from Morehouse, where he was named the top religion student. He got a full fellowship to study at UCLA.

“We’re three of hundreds upon hundreds nurtured by the church and a part of that village it takes to raise a child. The Black church in general and Zion, in particular, has been that village for us.”