Black Legacy Families, Installment III: The Eures Making Arts and Activism the Family Business

by Leo Adam Biga

Artistic expression and humanitarian concern come as natural to the Eure family as breathing. They own a history as artists, entrepreneurs, activists, advocates, educators and ministers.

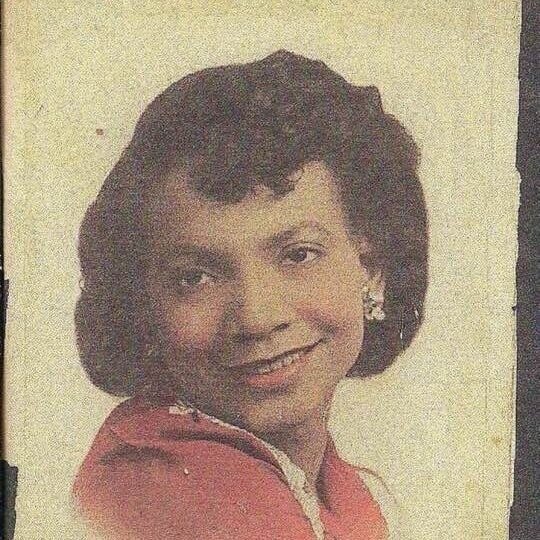

Albert and Dorothy Eure circa WWII. Photo credit: Eure family

The thread of that rich fabric traces back to early 20th century Harlem, New York. The Eures made their way to the northeast following a progression of freedom from Louisiana to the cotton, peanut and tobacco plantations of Virginia to the Carolinas to New York and New Jersey. The man who transplanted the family line to Omaha, Albert Eure Sr., was a dancer’s son. In the mid-1940s, he married budding actress and activist Dorothy Jane Watson whose father was a storyteller and sister a minister. The dye was cast.

The mother and four sons, each touched by the spirit of protest, engaged the community as socially conscious poets, playwrights, actors and directors. Two sons became preachers. Younger generations continue this kinship legacy as creatives and change agents. The family’s legacy as artists and activists who uplift and inform is featured in the 2006 book Engines of the Black Power Movement by James L. Conyers Jr.

“The power of creativity has always been a force in our family,” said Tyrone Eure, the youngest of Albert and Dorothy’s children. His brother Harry added, “Dad and Mom both taught us compassion through the way they raised us and through the expression and utilization of art and music. It created a very artistic, humanistic environment.”

In his role as family grio, Harry noted, “It is believed our family received the name Eure during our family’s slave bondage by white French slave owners and/or traders during the time of the Louisiana Purchase.

Harlem matriarch Mollie White-Coker, a seamstress by trade, was matron of a Prohibition-era speakeasy and owner of a diner. She also held real estate interests. During the Harlem Renaissance her daughter Louise Katherine Eure-Jackson found success as a professional dancer. In addition to being a Cotton Club show dancer, light-hued Louise was able to pass as a performer in white establishments.

Louise’s first husband, Harry Eure, was a Harlem hustler and numbers-runner when not working legitimate jobs. After her dancing career, she cleaned the upper New York state resort homes of Broadway luminary Helen Hayes and Hollywood star James Cagney. When Louise’s husband died due to complications from chronic health problems, she married Buster Jackson, a boilermaker and jack-of-all-trades. He became step-father to Louise’s son Albert Eure, who ended up in Nebraska for World War II military service. Attached to a segregated unit at rural Harvard Army Air Field south of Lincoln, Eure and fellow Black enlisted mates made their way to Omaha for weekend furloughs to unwind on The Deuce (North 24th Street). It was during a USO dance at the Dreamland Ballroom where the dashing, uniformed Albert fell for the dreamy Dorothy. They made a cover magazine-worthy couple with their movie star good looks. They lived for a time in New York, where their eldest, Albert Jr., was born, before returning to raise their family here.

Of his father, Harry Eure said, “He grew up very rough between Harlem and Nyack (N.Y.) after his folks broke up and his real father died. He always said he didn’t want to raise his family in Harlem. He wanted to get away from the hustle and bustle, the crime. He loved Omaha. It was family-oriented. It reminded him of Nyack – a small city surrounded by countryside.” Summers, Harry and his siblings returned there to visit family.

A shipping clerk back East, Harry worked as a butcher on the kill floor at Cudahy meatpacking plant and was active in union politics. A bright man who loved music, he sacrificed his own creative ambitions to be a good provider. He met his soul mate in the go-getter Dorothy, whose father, Lawrence Malcolm Watson, grew up in the racially mixed coal mining town of Buxton, Iowa. His family migrated there from Virginia. Her mother was Mary Belle Newland. Her maternal grandfather, James Obadiah Newman, owned a successful trash hauling business. An uncle, Charles Watson Sr. was a prizefighter known as “One-Step Watson.” He trained Dorothy’s brothers, Jimmy and Larry Watson, when they followed him in the ring.

Big Love

Fueled by social justice indignation and ambition, Dorothy formed the group Tomorrow’s World while still a Tech High student to press the Omaha Public Schools for more Black educators. In an oral history she gave her son Darryl, she said, “We wanted equality and we wanted it now.” She and her fellow activists refused to settle for what their elders did. “We weren’t going to live under the segregated conditions they had lived under.”

Dorothy Eure. Phot credit: Eure family

“She always told us she envisioned a better world for her children,” Harry said of his mother. “She taught us we should plant seeds for the future of our posterity. Dad was the same way. Things were very difficult for Black people. But we still had a house of love and happiness amidst poverty. There were situations in the house that weren’t always good because Daddy was suffering silently within himself. Sometimes it would come out in his drinking. He could get riled up and roar like a lion, but overall he was very compassionate. He found the strength to rise up.”

Darryl Eure admired his father’s responsibility. “A lot of his friends would talk about leaving their wives and kids, but he always said, ‘I’m the one that brought you into this world, and nobody’s going to take care of you but me.’” Harry said his parents’ “integrity and character” embodied the Greatest Generation. “They looked out for not just us but for other families.”

“Dotsy,” as Dorothy was called, was a small but mighty bundle of energy. Steeped in the Black church (Zion Baptist), she also possessed a theatrical soul. Her father used to set her and her siblings down in the family living room to act out stories of life in Buxton. “He was a great storyteller,” she told Darryl. “I think from him alone came much of the acting ability in the Eure family.” As a young woman she acted in two Black gospel films, circa 1940s-‘50s, entitled God’s Beauty Parlor and A Sacred Beauty. She staged gospel plays at church. She was a domestic worker, lab technician and assembly-line laborer before training as a legal advocate and then paralegal. At the Legal Aid Society she advocated for clients seeking relief from onerous lenders, slum landlords, heartless utility companies and other exploiters. The devout Christian brought an evangelical zeal to the work. Her fierce humanism may have had its seeds in her ancestors escaping Southern slavery on the Underground Railroad.

“She was very strong-willed in what she wanted to do,” said Harry. “You couldn’t say no to Mom about anything. particularly when it infringed on her rights to express herself or us to express ourselves. One of the things she instilled in us was tenacity. She always encouraged us to be free thinkers, independent and strong.”

Dotsy volunteered with the civil rights facing De Porres Club and 4CL (Citizens Coordinating Committee for Civil Liberties). She and her boys were a familiar presence at the latter’s protests. The family church, Zion, was a bastion of activism and Dotsy was right in the thick of things. “Mom made a complete impact on the community,” said Darryl. “People like her put their lives on the line for justice and equality,” noted Harry. “They got arrested. Had jobs taken away from them. Nevertheless they were determined we would be considered first-class citizens – that we wouldn’t have to drink from separate water fountains or have to sit in the back of the bus.” Dotsy’s fervor carried her to the 1968 Poor People’s March in Washington DC. Her efforts to desegregate her hometown’s separate and unequal public schools informed a lawsuit brought by Black mothers that forced the OPS district to enact busing. She and fellow activist Lerlean Johnson have a street named after them.

Darryl has “no doubt” his mother would be a Black Lives Matter warrior today. “She would be protesting out in the streets right now.” Her sons joined her on picket lines, pray-ins, sit-ins and marches. Demonstrating instilled resolve. “Through that experience you get stronger internally within yourself,” Tyrone said. “Growing up, the siblings were privy to civil rights discussions she convened at the family home. “We had all these people come to the house. I knew from that point Mama was different – that she was an organizer and a connector of people to bring about change,” Tyrone said. “She always found a way to pull people together and unite them. I admired her for that.”

Ernie Chambers was a close confidante. “Ernie had a special bond with Mom,” Darryl said. “He always knew he could count on her. He would often come over and talk about some specific issue. That’s how we all got to know Ernie.” The local civil rights movement centered right in the Eure household with those confabs. “While we listened to them we learned at the same time,” Tyrone said. “Those meetings were history lessons.” The education expanded from there. Harry recalled joining his mom at the Omaha Star for De Porres Club meetings. “They were very strategic. They had forethought as to how this would play out. Whatever picketing or demonstration they planned, they were articulate, precise and thought it through like a chess move – the political-social impact and public optics of it.”

“Martin Luther King Jr. made a big impression on me,” said Darryl. “I started reading everything he did, the books he read, the words he produced. I memorized his speeches, Everything related to Malcolm X, too. I also came up under Ernie Chambers, who had a big influence upon me, as did my mom.”

Segregation regarded as history today was the Eures’ reality. “We sat in the back of the bus. Even movie theaters were segregated,” Tyrone said. “I remember going to see Snow White and having to go up to the third balcony. It was disheartening. We went to Peony Park and couldn’t even go swimming. All these things affect you on some level. But through it all Mom and Dad instilled in us strength and determination that we could rise above everything. We were determined to make the world a more livable place.”

Ugly reminders of racism were never far away. “Dad used to take us for Sunday drives,” Tyrone said, “and this one Sunday we all piled into his new Studebaker for a drive through the Miller Park neighborhood, which was entirely white. All these people came from watering their lawns and barbecuing and told us to get out, calling us names. We got chased out.”

Arts and Activism

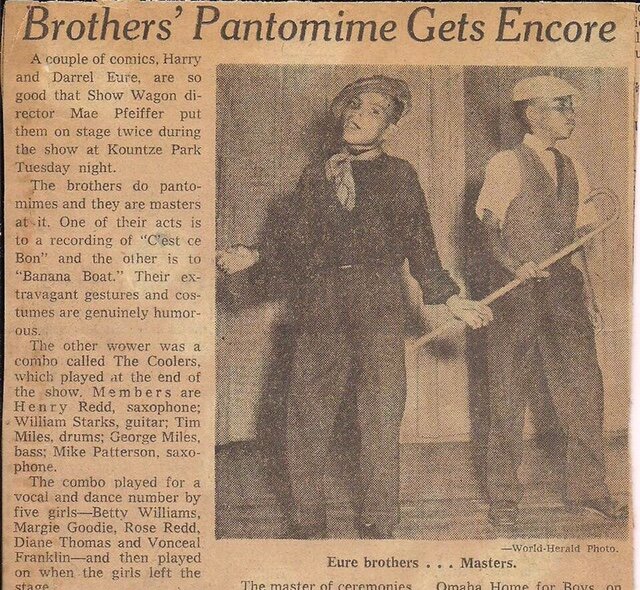

Home offered sanctuary from hate. The boys were natural performers and with their parents’ encouragement imitated popular Black entertainers. They called it “Showtime.” “It was a family event,” Harry said. “Everybody joined in, even Dad sometimes.” The activity harkened back to when Dorothy’s father acted out stories. When the family’s lone television set went out, this home entertainment became a nightly routine. Meanwhile, the most precocious siblings, Harry and Darryl, took tap dancing lessons. Their parents shaped the brothers into an act, billing them as the Northside Review. Much time went into rehearsals. “Dad and Mom often directed, providing on-point critique, making sure our performances were perfect in every way. Our rehearsals were always family-fun, creatively shared, and a bonding experience and exercise for us all,” said Harry.“ The duo won local Show Wagon contests. They performed dance routines, pantomimes, lip-synching and comedy skits at area fraternal clubs, theaters and civil rights rallies, touring as far west as Lincoln and as far south as Nebraska City.

Their dance instructor proposed taking them to Hollywood and New York, but Dotsy wouldn’t allow it. She did permit Harry to audition for a part in an Omaha Community Playhouse production of A Raisin in the Sun. He won it. The brothers’ academics didn’t suffer due to performing. Their father wouldn’t have it. “He always told us education is the thing that’s going to liberate you,” Harry said. “He had this phrase, “I’ve got four jacks – trying to make kings.’”

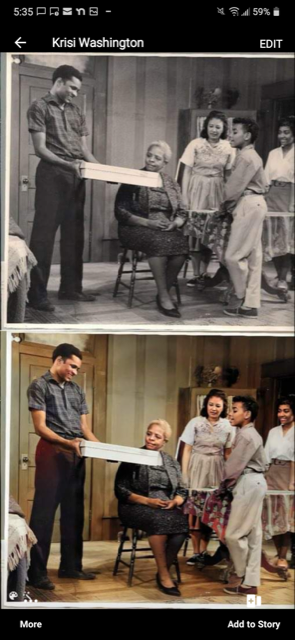

Afro Academy of Dramatic Arts rehearsal. Phot credit: Eure family

Arts and activism were interchangeable with the Eures. “We would go picket and march downtown for open occupancy laws,” said Darryl, “and then go to the (Omaha) Board of Education to try to get some things done. A group of us students left Central High one day and went down to Woolworth’s department store. As Blacks, we could go in and order but we couldn’t sit at the counter. We were going to break that up, so we sat down at the counter. Security was called and ushered us out. Police officers beat us up right in front of the store. I ran back inside thinking I could get some help. I fled to a tunnel under the street that connected to Brandeis department store, where I knew a Black security guard. He hid me in a closet. When I came back out, the police paddy wagon was there. From the station I called two people – my mother and Ernie Chambers. He was right on the spot, laying the boom on everybody. He and my mom raised a big ruckus.”

By 1968 Darryl and Harry were “seasoned” veterans of the civil rights movement. At Central Darryl co-founded BUSS (Black United Students of Soul) to agitate for Black Studies, the elimination of literary works containing offensive portrayals of African Americans, more cultural sensitivity by white educators and more inclusion of Blacks in extracurricular activities. Darryl wrote his first play, Uncle Tom’s Revelation, but the principal refused to allow it to be performed until protests by Black students and community leaders prevailed upon him to reverse the decision.

Darryl, Harry and Tyrone protested George Wallace’s 1968 presidential campaign appearance at the Civic Auditorium. They all got caught up in the resulting melee, with Tyrone chased by a baton-wielding cop around the arena. “All hell broke loose there,” said Darryl, whose friend, Howard Stevenson, was later shot and killed by police when the arena fracas triggered rioting and looting on the Near North Side. By then Darryl and Harry were both in college, On campus and off they spoke truth to power via protests against racist policies at school and in society, the Vietnam War and police brutality.

Afro-Academy of Dramatic Arts

Then, in 1969, 14-year-old Vivian Strong was wrongfully killed by a cop, touching off destruction along North 24th Street. Coming as it did in the wake of the assassinations of Malcolm X, MLK and Bobby Kennedy, and a community under siege, the Eures decided to make their creative gifts instruments in raising Black consciousness and unity. Thus, Dorothy joined Darryl and Harry to form the Afro Academy of Dramatic Arts in ’68. One of its first plays was an original by Darryl that equated Strong’s killing to Emmett Till’s murder.

News coverage of Darryl and Harry Eure's pantomime act. Photo credit: Eure family

The academy found followers among Black Panthers, and underground newspapers. They wore their Black Love loud and proud in afros and dashikis, giving the theater cachet and making it the subject of law enforcement surveillance and harassment. Undaunted, the academy pressed on “filling a need,” Harry said, “particularly with the onset of the Black Power movement, for expressing identity and independence.” He added, “We wanted to say, this is what we are, this is what we’ve lived through, this is our experience as Black people. What had been presented by predominantly Western culture and media did not characterize a condition we recognized. We didn’t feel represented. Black folks oft times depended too much upon acceptance of white folks – to the point we couldn’t accept ourselves for what we are.

“We were putting ourselves out there. It was a learning thing for not only Black people but for all people. The theater gave us an opportunity to express ourselves culturally and to assert new definitions politically and spiritually. It was about self-determination.”

Harry Eure in costume, flanked by two actresses, at a Descendants of DeWitty reenactment. Photo credit: Eure family

The academy was birthed at the Wesley House, a community center where many Black-led initiatives launched. Then it was given space in a building near 24th and Ames, where the Eures built a performance hall. “A lot of people had never been to a play,” Harry said. “We would go out on the street and bring people into the theater. The people that came were astonished. Some came back again and again. Some joined the Afro Academy and worked in plays themselves.” After the academy was vandalized by racist graffiti, a former church at 30th and Izard became its longest lasting home. Over time the academy produced works by Lorraine Hansbury. Douglas Turner Ward, Amiri Baraka (aka LeRoi Jones) and August Wilson as well as original works by Harry and Darryl. Dotsy developed a children’s theater wing.

Classes were offered in dramatics, dance, music and art. Instructors included top Omaha creatives Preston Love Sr., Claudette Valentine and Oran Belgrade. Some folks (John Beasley, Adrienne Higgins) who went on to larger success passed through as students or performers. Some moved onto the Negro Ensemble Company in New York. “A lot of creative, talented people in Omaha were participating in it,” said Harry. The troupe toured productions across Nebraska and Iowa and performed various material on Black-owned KOWH radio as well as on KETV and other local television stations.

Harry’s daughter Simone Jones recalled the excitement generated. “I have a strong memory of the energy the theater elicited. There was always a sense of artistic cooperation and thriving.” Her mother, Charlotte Nelson, wrote plays, led African dance classes and helped curate its vision. Simone’s father wrote, directed and acted in plays. “I would watch my parents transform into characters, teachers or directors and always be in reverent awe,” Jones said.

The academy provided an early stage for spoken word and performance art. “We did Poetry in Motion – a mixture of dance, music, spoken word and other creative expressions,” Harry said.

Community Engagement Ministries

Like their mother, the sons became public servants. Harry was youth director for GOCA (Greater Omaha Community Action), director of the Lutheran Church-based Project Embrace and an Omaha Planning Department community developer. Since the academy’s closure in the early-’80s, he’s continued performing on various stages. He’s done Verbal Gumbo poetry readings and Descendants of DeWitty historical reenactments. His thespian talents were passed to his daughter Ashley Eure, who acted at The Rose. She once had ambitions of pursuing an acting career. Fond childhood memories include her father taking her to plays. Often he was in them.

“My father is the smartest person I know. Quirky, but brilliant. He was the first to get me excited about science. I learned about space and physics through him. He may be deeply into the arts, but he's amazing with numbers as well. A historian, mathematician, scholar, actor, writer, playwright, activist. He’s a good person, too,” said Ashley.

Decades earlier, her uncle Darryl meant to enter show business. “I wanted to be on Broadway.” he said. He met his wife Gretchen performing at the Omaha Children’s Theater. His career priorities changed after being drafted into the U.S. Army and refusing induction on conscientious objector grounds. He was ordered to report for basic training at Fort Leonard Wood (Mo.), where his convictions were severely tested. “I protested the whole time I was in the military,” he said. “I participated in boot camp. However, I refused to pick up a gun. I was sometimes confined to barracks.”

Verbally abused and berated, even threatened with federal prison, Eure never felt so afraid or alone, though he knew he had support back home. “I had a lot of people helping me, including my mom and community advocate Rodney Wead. I was writing to Ernie Chambers.” After months pressing his case, he finally got a general discharge under honorable conditions. Disillusioned, he found a new path as a minister, which continued a family line begun by Dotsy’s oldest sister, Marion Jones. “I wanted to be able to say I’m going to be more than a song and dance man,” Darryl said of his own decision to enter the ministry. “I wanted to feel I made a mark in this world to help make things better for all people.” His sermons deliver the fire of his plays. “This year I will have been the pastor at Freestone Baptist Church for 35 years.”

Dotsy lived to see Tyrone ordained as well. The prophetic gospel minister shares scriptural-based messages through poems, books, films and social media posts. He’s authored two faith-based visionary novels, The Test and Dear Joseph. He also writes, directs, shoots and edits short films, including The Upper Room and Route 66. He’s developing a feature film project.

The U.S. Army uniforms of Albert Eure and his son Darryl Eure. Phot credit: Eure family

The brothers’ church calling followed the example of their aunt. “She was a great influence,” Darryl said. “She was one of the few Black women ministers who then became pastors. At that time many of the churches frowned upon women ministers. But she could preach. She knew the word of God. I learned a whole lot from her in the ministry. Marion Jones was phenomenal.” Even Harry did his share of preaching as a Zion youth minister, but he ultimately didn’t feel the call. Though Darryl now leads a congregation, he hasn’t abandoned performing. He portrays MLK and Malcolm X in Black History Month presentations. The creative work he, Harry and Tyrone do today continues the family’s Afro Academy ministry.

The shy Eure brother, Albert Jr., who died in 2010, rarely expressed his own innate creative talents publicly the way his demonstrative brothers did. But his impact was felt the same. “Unlike us Albert was happy not being in the spotlight,” said Tyrone. “He was a quiet giant,” said Harry. “He wasn’t as vocal, but Albert spoke in volumes with his presence and his character. He was a good writer, too. He called himself “the silent poet.’

Harry’s daughter and son-in-law, Simone and Tony Jones, followed the family’s humanistic heritage as Boys Town parent-teachers. Their three children grew up under the same roof as the surrogate kids the couple raised.

Simone and her half-sister Khalilah Yasmin are creatives with strong fashion senses. Khalilah is a writer, actress and model based in Las Vegas. Though she grew up separately from the Eures, Khalilah appreciates the genetic predisposition to creativity that runs through the family. She is the author of several books, including Matador.

Simone and Tony’s oldest son, Justice Jamal Jones, is a recent New York University graduate who’s following the family’s creativity heritage as a multimedia artist, actor and filmmaker. His short film How to Raise a Black Boy is winning festival prizes. Justice got his start in theater at the Omaha Community Playhouse and The Rose.

To Everything, There is a Season

As new generations of Eures carve out paths as creatives and doers, they are mindful of the elders and ancestors who blazed trails before them.

Simone feels blessed to have known Dotsy, who embodied a self-actualized Black woman. “She took me under her wing. In everything she did she said, ‘Simone, we’re going to do it together.’ I learned from her ultimately there’s no place I don’t belong. I spent many days hanging out with her at her paralegal job. That was like a treat. That’s probably when I first realized she was different. I never saw her afraid of any situation.”

The Eures enjoying some family time; the brothers, left to right, are Darryl, Harry and Tyrone. Photo credit: Eure family

In the oral history interview she did, Dotsy described the self-affirmation she projected. “I never felt myself as second-class. I just can’t ever feel like that. I wasn’t born that way to feel it. I always did think I was ahead of my time.”

Dorothy Eure never conceded anything as a Black woman of little means or standing. “Those things were never an issue for her,” said Simone, who saw her elder demand action from elected officials, judges, attorneys and corporate executives. “That’s when I was like, Okay, this woman is not playing around. I realized she would not take no for an answer. No meant to her, Oh, just not right now, you’re not the person I need to talk to – where is the person I need to talk to?’ Her example taught me we’re all human, we all have needs, and we can work with each other. She stood up for whoever walked in her office and needed help. She would fight on their behalf. She was a fighter. She gave that fighting, never-give-up-spirit to me.”

Dotsy died when her granddaughter Khalilah was 11, Though Khalilah only saw her sparingly when growing up, she feels she’s inherited Dotsy’s spirit as a visionary and creative. “I am honored to be her granddaughter. One day, I’d like to make a powerful impact on the world in my own way.”

Khalilah and others recall Dotsy’s generosity knowing no bounds. Witness the Christmas party Dotsy organized that morphed from giving gifts to a few neighborhood kids into a major community event gifting hundreds. It started in the Eure basement. After outgrowing that space, it relocated to the North Christ Child Care Center. The party included food, refreshments and Santa.

Recalled Darryl. “I would drive her around to stores to get these toys. One year she was looking for some Black dolls and she didn’t find any at the four stores we visited. She had me take her back to each store so she could fuss at the managers. ‘You’re supposed to have some dolls that look like us,’ she said. ‘I’m not going to take this anymore. Next year at this time y’all better have Black dolls.’ And next year they all did. Mom would not give up. She wasn’t the CEO of anything, but she wasn’t afraid of talking to whoever.”

Her outreach never ended. Once, she and Darryl delivered a large pantry order to a house. “Some young men were inside and none came out to help us,” he said. “Oh, my goodness, Mom went in and she busted everyone of those young men. ‘Y’all going to go outside and help us bring this food in here, and then we’re going to go look for jobs for all of you. How many of you have graduated school?’ That was Mom. She’d fix up the whole family.”

“She was a little lady with a big spirit,” said Tony Jones. “As I came into the family I saw that compassion and love for community. It led Simone and me in the direction of going out to Boys Town (as parent-teachers). “I saw her reaching out, being an advocate for kids. It led me and Tony down the road of helping others,” Simone said. “I didn’t realize the impact we would have as a result of the role modeling I saw with my grandmother and grandfather. Having both been influenced by strong African American grandparents, we simply have old school values. We often felt we were being blessed by our ancestors to make it through difficult times.” Justice Jamal Jones reveled in the Arcadian life his parents gave him at Boys Town.

“We were always outside playing, running, joking, laughing,” he said, “and then we got to come home and my parents made dinner and we talked and watched movies. It was always so beautiful and I hold it so dear in my heart. It’s one of the greatest gifts my parents have ever given me.”

Giving back is a family trait. Simone’s pursuing a master’s of public health degree with the goal of addressing health disparities among African Americans. Tony, a Boys Town graduate, is today its alumni director.

The couple also appreciate what her grandfather gave them. “Granddad was very consistent,” Simone said. “I learned that without consistency you can’t be successful. He displayed a calm-natured willingness to just keep moving forward.” “He was ‘a cool cat’ as they called him back in the day,” said Tony, who cherishes memories of Albert schooling him on jazz while chilling on his adopted grandparents’ front porch.

If North 24th Street Could Talk

The patriarch’s sons often wondered why their father, besides love, opted for Omaha over New York. Darryl recalled, “Daddy told us, ‘When I came here North Omaha had everything Harlem had. We used to have Nat King Cole, Count Basie and all the big entertainers come.’ They’d play downtown and then after they got done playing there they would come to North Omaha.”

Street sign recognizing Dorothy Eure and Lerlean Johnson photo credit: Eure family

“Dad said you had to ‘bugaloo’ across 24th Street’ the traffic was so thick,” Harry said. “Whatever you wanted you could find it on 24th Street. It was jumpin’ or as he liked to say, ’It was leapin’ – there was so much to do and so many things to see.”

The sons are old enough to recall that heyday themselves. “North Omaha was vibrant, I’ll tell ya,” Darryl said. “It was the best place in the world to me. It was a different place than it is now. When we were coming up we had so much going on. That’s one of the things I really miss. That’s one of the reasons we stayed here. With the Afro Academy we thought we were going to turn this community around. Twenty-fourth and Lake was the heart. We were segregated. We were black-lined (red-lined), But at the same time we had the vibrancy. We had a lot of pride in our neighborhoods. A lot of that’s gone now.”

The Eures saw their beloved community ravaged, first by the 1969 riot, then by the “monstrosity of the North Freeway tearing right through North Omaha, dividing it up,” said Darryl. “Then they put the Hilton Hotel right in the middle of 16th Street, almost to block us off from the downtown business district. They were literally shutting North Omaha out. The whole community fell apart. There was no money to rebuild. We found out later urban renewal money that was supposed to go to North Omaha ended up building up the riverfront.”

Harry, who worked in city planning then, said, “Even though the basis for obtaining those federal community block grant funds was to address the blight in North Omaha, unfortunately North Omaha didn’t get the bulk of the money.” That disinvestment, Darry said, “devastated North Omaha. I don’t know if it’s ever going to recover.”

Tyrone said a systemic imbalance exacerbated the situation. “Whites controlled the money to a certain degree. With no more resources given to that area, economic development depended upon white economic power. A lot of businesses (in North O) went under after the money left.”

“Investment was hard to come by in North Omaha post the riots,” Harry said. “It’s a shame. That stigmatism didn’t have to persist that long. Other communities – Benson and South Omaha – were nurtured through entrepreneurship and big business investing in those areas. Banks supported their economic development.” “It’s racism,” said Tyrone. “It’s using isolation as a weapon. Isolate a people and downgrade them economically by denying them resources.” Harry rues the piecemeal way development proceeded in lieu of a comprehensive, cohesive approach “that never happened.”

The decline that followed saddens the family. Harry recalled taking his father to see what became of North 24th. “My dad said, ‘Oh, my goodness, it’s a cemetery with lights now.’” The Eures remain committed to its revival but their focus these days is more spiritual than temporal.

“We all have a ministry and a responsibility to carry forth our spiritual destiny,” said Tyrone. “Through the evolutionary process you transform into hopefully something that will benefit not only yourself but the community. I think that’s what true art and true creativity does. It expands, it broadens.” Harry also believes in the transformative power of art and calls on his Black brothers and sisters to preserve their cultural legacy. “We’ve got to revere and appreciate the value of our historical culture presentations. There are lessons there that could be transformative into the future. Some portions of our legacy have not been transmitted, communicated well enough to our young people. There’s a disconnect between what was, what is the present and what the future will be, and that’s unfortunate for us as a people.”

Generations, Connections, Legacies

Harry’s heartened to know his children and grandchildren suffer no such disconnect. Despite the fact Dotsy was gone before he was born, Justice feels a deep connection, “She empowers me. I think Black women have been at the forefront of creating change in America and I think probably the most important thing I get from her is that she got a lot of stuff done and she didn’t take shit from people. For me as a Black queer person she empowers me to have that same kind of energy to move forward irregardless.”

When it comes to legacy, Simone Jones marvels at how her grandparents were able to “navigate life with such positivity and vigor,” adding, “I carry the legacy of all of my grandparents wherever I go – their determination and fortitude. Black lives have always mattered. Perhaps this is what sustained my grandparents and ancestors to continue to work hard for their families despite the challenges of racism. I have continued respect for what they endured.”

According to Ashley Eure, a quote that’s always resonated with her – “I am my ancestors' wildest dream” – is exactly what comes to mind when she thinks of her family. “There's such a vast and rich legacy of so many untold stories and struggles that I am a product of. I have a deep sense of pride and resilience knowing I stand on the shoulders of giants. I am because of who they were. I feel so appreciative of what they did.

“My grandmother's activism and my father's love for the arts are certainly embedded in me. Although I may not be in the streets or in courtrooms with my fists held high, I am still effectively bringing about change by occupying the space I'm in. As a Black female engineer, I've been able to show and prove that we are capable. We can be strong and destroy false narratives.’”

Leave it to the family’s new generation creatives to put the family’s legacy in perspective. The words of activist Angela Davis remind Khalilah Yasmin of the high-minded way the Eures have conducted themselves as community advocates: “You have to act as if it were possible to radically transform the world. And you have to do it all the time.” “I think the Eures represent an ever-changing idea of what it means to be a Black family in America,” said her cousin Justice Jamal Jones. “The beautiful thing is that the family really hasn’t dispersed. Throughout trials and tribulations, celebrations, ups and downs, everyone is still together, and I do think that is the work of Grandma Dotsy and what she taught her kids. It’s a feeling of pride, yeah.”