Bonus: Why the Illegal Search of Mondo's Home Did Not Lead to a New Trial

By Kietryn Zychal

Former Black Panthers, Ed Poindexter and David Rice (Mondo), were found guilty in 1971 of booby-trapping a suitcase bomb to kill Omaha Police Officer Larry Minard by a jury of 11 whites and one Black man. Mondo appealed their verdict based on the illegal search of his home where questionable evidence was gathered that was used against him in court. He won in two federal courts and the state appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. On July 6, 1976, the decision Stone v. Powell/ Wolff v. Rice denied him a new trial to prove his innocence. While Americans enjoyed the Monday morning afterglow of coast-to-coast celebrations of the July 4th Bicentennial and the virtues of democracy, the Supreme Court chipped away at their constitutional protections.

Because of this,

Mondo’s trial attorney, the late David Herzog, pointed out that he was held in violation of the Constitution for 46 years until his death in prison in 2016.

Because the guilty verdict was not overturned, some believed the U.S. Supreme Court “upheld” the conviction of Mondo and Ed Poindexter. It did not. The Court changed the procedure for filing Fourth Amendment claims and made the new rule retroactive. Stone v. Powell stopped prisoners from appealing illegal search and seizure claims arising from state prosecutions to the federal courts on a writ of habeas corpus as Mondo had done. Instead, they were made to appeal such claims from the state supreme court to the U.S. Supreme Court on a writ of certiorari. Notably, the Court did not overturn the finding of the federal courts that the search of Mondo’s house was illegal.

Herzog was confident that the affidavit for the search warrant of Mondo’s house lacked probable cause, and that federal courts would overturn his conviction. He did not know, however, that the U.S. Supreme Court was looking for a way to diminish the use of the exclusionary rule— the principle that evidence illegally obtained cannot be used against a defendant in court. Herzog had no clue that his 23-year-old client would one day die in prison as a 69-year-old man because of Stone v. Powell/Wolff v. Rice.

Events leading to the illegal search

An unknown man made a phony 911 call at 2 a.m. on August 17, 1970 claiming that a woman had been dragged screaming into a vacant house at 2867 Ohio Street in Omaha, Nebraska. Eight officers responded to the call and discovered the caller had given a vacant house as his address. They heard no screaming and neighbors who came out of their homes told police they had not heard screaming moments before. Furthermore, officers had received a written warning that summer to be suspicious of any kind of box that might be a bomb.

The officers saw a suitcase lying in the doorway of 2867 Ohio. Five of them stepped over it and went into the vacant house. Officer Minard was killed when he inspected or tripped over the suitcase while exiting.

Assistant District Attorney Sam Cooper listened to the 911 call. He said in a 2005 deposition that he and Omaha police detectives suspected the bomb-makers were militants from the National Committee to Combat Fascism (NCCF) — a successor organization to Omaha’s disbanded Black Panther chapter. Lt. James Perry told a private investigator in a 2002 interview that you would have to be “a sap-sucking idiot not to know who was responsible for the bombing.” According to Cooper, the guilt of the NCCF was assumed and no other leads were developed.

DUANE PEAK

Five days after the bombing, the investigation was focused on Duane Peak, a 15-year-old who was seen carrying a suitcase on the day before the bombing. His sister said she drove him to 28th and Ohio several hours before the explosion and he carried the suitcase with him.

During the afternoon of August 22,

police searched the headquarters of the NCCF on 3508 N. 24th Street with an arrest warrant for Duane Peak, though he did not live there.

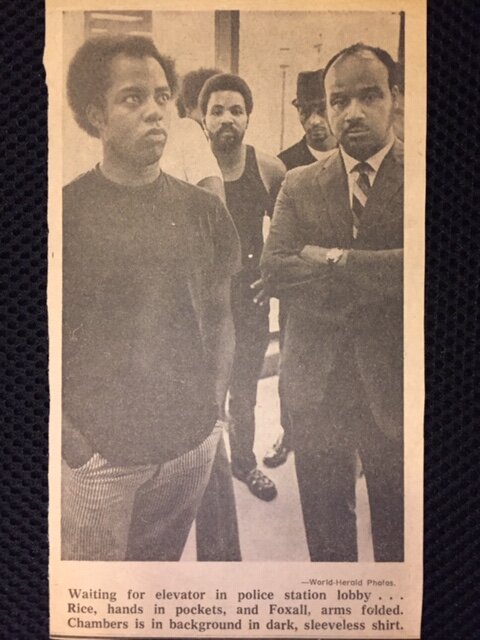

The initial arrests

NCCF members Ed Poindexter and Robert Cecil were arrested after the search of the headquarters on August 22, which yielded some guns and a calendar with the date August 10 circled in red. Ed’s clothing was seized and taken to the ATF laboratory in Washington, D.C. by Agent Tom Sledge. A few days later, Ed was released from custody for lack of evidence— in his underwear— as the police no longer had his clothes.

Later on the night of August 22,

Police went to Mondo's house at 2816 Parker Street with the same arrest warrant for Duane Peak— though he did not live there, either.

The search of Mondo’s house

Police reported they found the front door of Mondo's house wide-open, the lights on and the television playing. Some of the officers went to get a search warrant for the house based on a tip from an unnamed informant who said that if the NCCF had dynamite, then Mondo’s house would be one of the places they would store it.

Mondo had gone to Kansas City for the day to speak at a rally in support of Black Panther leader Pete O’Neal. He locked his house because it had been repeatedly broken into. The open house establishes that someone went in Mondo’s house immediately before the police searched it. Mondo always claimed that dynamite and blasting caps were planted in his house.

The police report filed after the search, quoted below, is a curious document. Additionally, the testimony from officers about finding the dynamite changes over the years.

The report states,

“Found in the basement in the northwest corner, 15 sticks of DuPont, Red Cross, 50% Nitro. Also found in the house, two rifles, one shotgun, and one pistol. These were found by Patrolmen Howard, Taylor and Steimer. Also found were four blasting caps. These were found by Sgt. Pfeffer under a piece of furniture in the front living room. Found by Sgt. SWANSON in the living room against the east wall was a Marathon 6-volt battery of the type that could be used to construct a bomb."

The police report written shortly after the search mentions the name of each officer who found the guns, the blasting caps, even the battery. But it neglects to mention who found the most incriminating item— the dynamite. It is especially odd, because the man who testified at the trial that he found the dynamite was the same man who wrote the report, Sgt. Jack Swanson. Swanson referred to himself in the third person regarding the discovery of an ordinary household battery, but he does not mention he found the dynamite.

There is no photographic evidence that dynamite was found in Mondo's basement.

The police did not take a photograph of the box of dynamite allegedly found there until they put it in the trunk of a police car.

Later that night, Mondo was returning to Omaha and heard on the radio that the police had searched his home and claimed to find dynamite. He actually found humor in the situation, even though he was frightened about what was going to happen to the rest of his life.

Trial and appeals

Mondo and Ed Poindexter were tried in a single trial. Duane Peak accused Poindexter of building the bomb in Mondo’s kitchen in front of him on August 10— the date circled on the calendar seized from NCCF headquarters.

The dynamite allegedly found in Mondo’s basement was presented as evidence at their consolidated trial, tainting both of them because Poindexter was accused of building the bomb in Mondo's house.

At the trial, Sgt. Swanson testified that he found the dynamite in Mondo's basement. Sgt. Robert Pfeffer testified that he personally never went down there. Contradicting their testimonies three years later, Swanson said he wasn’t sure who saw the dynamite first and Sgt. Pfeffer gave a detailed description of his activities in the basement. These statements were given during an appeal hearing in federal district court before Judge Warren Urbom.

At the 1974 hearing, Lt. James Perry told the judge that Duane’s sister claimed that Ed, Mondo and Duane were “constant companions”. This is not corroborated anywhere in the record. In the summer of 1970, Poindexter was a 26-year-old Vietnam Veteran and, like Mondo, he did not spend time with 15-year-olds. Judge Urbom said he found Perry’s testimony to be “not credible".

Urbom ruled that the police did not have probable cause to search Mondo’s house because the affidavit for a search warrant contained uncorroborated speculation by an unnamed informant. Judge Urbom ordered a retrial for Mondo without the dynamite or blasting caps-- applying what is commonly referred to as the exclusionary rule. His decision was affirmed by the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals.

Ed Poindexter was denied an appeal of his conviction based on the illegal search of Mondo’s house because he did not live there. Illegally obtained evidence was presented in court at Poindexter’s joint trial with Mondo, yet he was prevented from appealing his conviction because of it.

Supreme Court

Chief Justice Warren Burger did not support giving guilty prisoners a new trial without the evidence that proved their guilt. He advocated reducing the use of the exclusionary rule, which allowed evidence to be thrown out if obtained illegally. Both Mondo and the other appellant, Lloyd Powell, were African American men. The decision Stone v. Powell/Wolff v. Rice became an important step in scaling back prisoners' ability to appeal Fourth Amendment claims. The procedural change took away the prisoners’ pathway to appeal through the federal courts on a writ of habeas corpus, requiring them to appeal illegal search and seizure claims from their state supreme court on a writ of certiorari to the U.S. Supreme Court. This requirement was applied retroactively to Mondo's case. The Court reasoned that state courts could offer a "full and fair" opportunity to litigate Fourth Amendment claims arising from state prosecutions.

Mondo was represented during oral arguments before the Supreme Court by Father William Cunningham, a Jesuit priest and law professor from California. Cunningham told the Court his client was innocent. He said the police planted dynamite in his house, they did not simply search it illegally. The Supreme Court questioned Cunningham about the dynamite in his client’s pants. Cunningham replied that they could have planted that, too.

When confronted with the possibility of planted evidence, the Court said that was “quite a different question.” The oral argument primarily debated whether or not the Court should continue to hear Fourth Amendment claims from state courts on habeas corpus. Ultimately, the justices decided against the plaintiffs.

This is the tragedy of Wolff v. Rice. The Court did not reverse the findings of the lower courts. The decision does not disagree with the Eighth Circuit's constitutional analysis. The justices recognized that Mondo's Fourth Amendment rights had been violated by the illegal search of his home and they ignored it.

Chief Justice Warren Burger wrote a separate opinion which stated that the exclusionary rule should only be applied when the prisoner had a claim of innocence or in cases where there was egregious bad-faith conduct on the part of the police— which is exactly what Mondo's attorney alleged during oral argument.

After the decision, Cunningham filed a writ of certiorari from the Nebraska Supreme Court as the new rule required, and was told it was too late; the filing deadline expired years ago.

If Mondo had been allowed back into court in 1976, it is likely Cunningham would have accused police of planting the dynamite as he had done before the Supreme Court. None of the trial attorneys had been willing to do that. The key witness, Duane Peak, would have been brought back to testify just five years after his initial trial. And the original 911 tape which was later destroyed by the Omaha Police would still have been in existence. Mondo had a chance of being acquitted in a retrial. But that chance was stolen from him by Wolff v. Rice, and no state or federal judge would grant him a new trial after 1976. Mondo died in prison in 2016, claiming his innocence to the end.