Navigating Systemic Racism: The Education You Never Got in School

1937 Home Owner’s Loan Corporation (HOLC) Map of Omaha.

by Leo Adam Biga

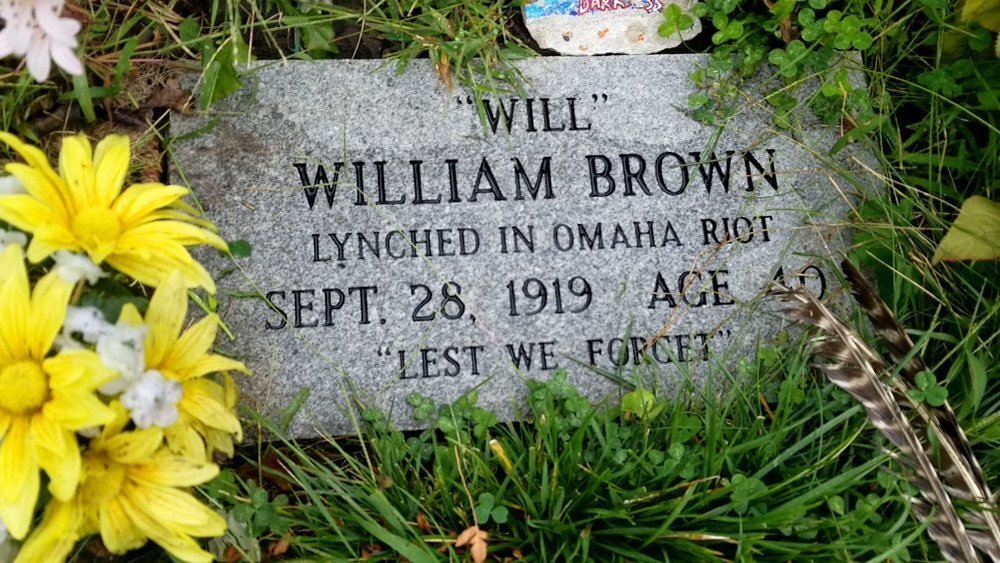

Depending on your point of view, Omaha may be the least or most likely spot for racial equity education to take hold. The city has its demons, some of which it’s been owning up to of late. The 1919 lynching of William Brown. Rampant red lining that created rigid geographic segregation. Disinvestment that atrophied the hub of Black Omaha after late ‘60s civil unrest.

The North Freeway’s severing of that same community. Separate and unequal public schools whose classrooms were integrated by court-ordered busing. Wrongful police and civilian shootings of Black residents by whites who escaped incarceration. A controversial conviction of two former Black Panthers whom many believe were innocent. Black disparities in poverty, housing, employment, education and healthcare that mirror and in some cases surpass national averages.

William Brown was the victim of a gruesome lynching in front of the Douglas County courthouse in 1919.

This historical context informs efforts by some local players to reckon with systemic racism in the wake of George Floyd dying last year when then-police officer Derek Chauvin pinned a knee to his neck and ignored pleas to relieve the pressure. Now that Chauvin has been found guilty of murder and manslaughter, the question is what impact this will have on a system built on mass incarceration and with a legacy of Black and Brown people dying at the hands of law enforcement.

The concept of structural racism has been around a long time. But it took Black Lives Matter (BLM) and the social reform protests of the past year to bring it out of academic circles and into public currency. That sea change may be why America is closer today than ever before to dealing with racial reconciliation and remediation. But given the labyrinth that structural racism represents, complete with generational oppression and trauma, experts say expectations about progress should be tempered. Undoing any entrenched system is a process. Undoing one that touches social, cultural, educational, political, historical and economic subsystems is a challenge for the ages.

Much of the local focus on unpacking systemic racism’s roots and expressions is being driven by the Sherwood Foundation, the Omaha-based philanthropic arm of Susie Buffett. Sherwood is funding in-person and online workshops for a wide spectrum of Omaha stakeholders conducted by the national Racial Equity Institute (REI) based in Greensboro, North Carolina. Sherwood’s support of the training is part of a record $12.6 billion in social justice giving recorded in the U.S. during 2020, according to the tracking service Candid.

REI co-founder Deena Hayes-Greene said what distinguishes her non-profit’s approach is the fact she and fellow facilitators “are organizers,” adding “Our work is organizing, building capacity, sharing understanding. We show up where we’re invited. We don’t solicit work. We don’t advertise. We don’t send anything out after racially-charged incidents happen because it’s just not how we do our work.”

“Our work is organizing, building capacity, sharing understanding. We show up where we’re invited. We don’t solicit work. We don’t advertise. We don’t send anything out after racially-charged incidents happen because it’s just not how we do our work.”

- REI co-founder Deena Hayes-Greene

Hayes-Greene said racism is so pervasive that it’s embedded in every community, region or sector.

“Racial inequity looks the same across systems, period. Omaha has an achievement gap, health disparities, disproportionality in child welfare, but so do communities everywhere. Our approach is about connecting the individual stories and history to the systemic-structural racism that was part of our country’s founding and a reality for centuries. Racial inequity exists in every system, without exception. We haven’t found a place where that’s not the case. There’s a universal framework around the structural arrangement of race. We think it’s important people see how their stories fit into the national story and history.”

Searching for Answers

Considered deliberations have been happening in many spaces since the 2014 killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. “There were statements of support and solidarity from private and public sector leaders, mayors, police chiefs and governors,” Hayes-Greene noted. “This was the tipping point to say this isn’t going away. It pushed this country in ways movements do.”

Nationally, some deep dives on systemic racism have followed, particularly The 1619 Project by the New York Times and the best-selling Isabel Wilkerson book The Origins of Our Discontent. The Episcopal Church in America is rolling out a Sacred Ground dialogues series on race. Lesley Dean, a member of Church of the Resurrection in Omaha, is convening state-wide Zoom forums within the Nebraska Episcopal Diocese around the Sacred Ground curriculum.

Meanwhile, corporations and organizations here and everywhere have incorporated commitments to DEI (Diversity, Equity, Inclusion) and condemnations of racism in their mission statements. The Greater Omaha Chamber of Commerce’s CODE (Commitment to Opportunity, Diversity and Equity) initiative has enlisted the participation of a broad range of members to create more inviting workplaces. Before REI took root here, similar work was being done by PRI (Policy Research & Innovation), which now goes by MORE (Movement in Omaha for Racial Equity), and by Inclusive Communities. On its website and social media MORE brands itself as “an antiracist organization fighting for racial equity in communities through engagement, education and advocacy.” Meanwhile. Inclusive Communities presents the Omaha Table Talk series and the LeadDIVERSITY program. The ultimate goal of the latter program, said Inclusive Communities deputy director Cammy Watkins, is to help workplaces become more inclusive and to train advocates in leading a broader community drive for equity.

“The Racial Equity Institute’s two-day, 16-hour workshop is a deep analysis of structural racism, how it was created, how it’s been maintained and how it impacts individuals today

- Tess Larson, Sherwood Foundation Associate

Sherwood Foundation program associate Tess Larson said her organization has made racial equity training available locally at scale as “a powerful complement to the DEI work already happening here. “The Racial Equity Institute’s two-day, 16-hour workshop is a deep analysis of structural racism, how it was created, how it’s been maintained and how it impacts individuals today.

Omahans need both: teaching individuals how to be intentionally anti-racist and attention to the systems-level, structural racism. You can change hearts and minds, but that won’t necessarily change systems. REI provides a framework for level-setting, shared terms and language, and a historical analysis of structural racism. These provide a solid foundation for community members to continue their journey toward understanding and achieving equity. The workshop content is very fact-based, laden with references to sources, and all of the information compounds over time.”

“People leave an REI workshop hungry for more knowledge,” Larson said, “and they will hopefully be able to plug into some of the local DEI efforts and programs.”

From February 2020 through February 2021 about 900 participants from some 165 organizations took the training in Omaha courtesy of Sherwood. New sessions are booked through mid-year. The heavy participation makes sense to Larson. “With George Floyd and then James Scurlock, all the protests, calls for peace, frustration, pain, miscommunication, it just seemed it couldn’t wait. People seemed hungry for knowledge. I think people were suddenly more willing to commit to a two-day workshop. Everyone seemed to understand the importance of the moment.”

A Conversation that Can’t Be Ignored

Mutual of Omaha is both a participant and a workshop sponsor. Vice president and chief diversity officer Angela Cooper said, “In 2020 we really came face to face with realities we couldn’t ignore. Our leaders engaged in listening sessions, both internally and externally. People were very open. I admired their courage in sharing. What we learned helped to shape all the actions we took.”

“Our chairman and CEO (James T. Blackledge) was among the first to take part. Since then his entire direct report team and several company officers have participated.”

-Gail Graeve, Mutual’s vice president of Community Affairs and Corporate Events and executive director of the Mutual of Omaha Foundation

Gail Graeve, Mutual’s vice president of Community Affairs and Corporate Events and executive director of the Mutual of Omaha Foundation, said, “It wasn’t a hard sell at all” to get the company to go through the training. “Our chairman and CEO (James T. Blackledge) was among the first to take part. Since then his entire direct report team and several company officers have participated. We saw the opportunity to influence externally as well, so we’re underwriting sessions for nonprofit partners to experience this, too. In the sessions we sponsor it’s a blend of our associates and community partners. I think it’s good for our associates to hear from others in the community and vice versa, and learn from each other.”

Lozier Corporation also sponsors the workshops.

Kids Can CEO Robert Patterson and his board chair attended the last in-person REI workshop in Omaha in early 2020 before the outbreak of COVID moved the trainings online. When racial injustice protests unfolded, he appreciated the perspective he gained from the training.

“I personally felt better prepared for everything that happened in the proceeding year,” he said. “I didn’t realize how many veils I had been seeing our history through until that workshop. It was really enlightening. It really helped me see the current events through a better lens.”

Unlike previous implicit bias training he’s taken, he said, “This began to get closer to the core of why things are the way they are and even why Omaha is set up the way it is. Race is such a huge determining factor of our community and our country that until we understand this we don’t understand anything. That’s why I think this is such an important training.”

“You didn’t give them resources, industry, economic development, good paying jobs.”

- Douglas County Sheriff’s Office Chief Deputy Wayne Hudson on red lining in Omaha.

Douglas County Sheriff’s Office Chief Deputy Wayne Hudson found the interactive workshops intense and informative. “As a Black native Omahan,” he said, “much of the content reinforced things I already knew about red lining, but I know most of the individuals I work with don’t come from these communities and don’t have a lot of cultural awareness.” Even with his background, he said he “never knew how extensive” systemic racism was around property and opportunity. “No wonder it took so long for certain neighborhoods to rebound. You didn’t give them resources, industry, economic development, good paying jobs.” he said.

Michele Bang, deputy chief of Police Services with the Omaha Police Department, also appreciated the connect-the-dots approach of the training.

“It provides you context as to how we got here and how the system is set up with winners and losers. It does exactly what it’s meant to do – challenge your perceptions. I mean, we all have our biases. It’s how we respond to those biases and then manage and check those biases.”

Several OPD colleagues have taken the workshop and she notes, “It has fostered dialogue and we have had to look at things. As police executives we do have the opportunity to engage with and challenge the public and our own family and everyone in between on this important topic. It couldn’t be more relevant. Given what 2020 provoked in all of us, you had to do it, you could no longer be too busy to do it. It’s the conversation that needed to happen.”

Hudson became an advocate for the training after he completed it. “I thought it was worthwhile and I wanted everybody to have the same foundational knowledge. That’s why I made it a requirement for all my captains and my crime lab director to go through it. When it comes to direction and leadership a lot of it comes from the top down. I wanted them to buy into it and then send it down to the lieutenants, the sergeants, the deputies.”

He finds it refreshing the material doesn’t bash cops or any one field or group. “It’s all about procedural justice, implicit bias, how can we build better communities, how can we sit down and have conversations and humanize one another.”

Patterson wants his entire Kids Can team to participate, he said, “because this is something we need to tackle from all sides.”

Camas Holder, Eastern Service Area administrator for the DHHS Division of Children and Family services, said unpacking the workshop’s themes has fallen to an internal equity team. “We meet monthly to ensure the time and effort we spent was not wasted. We’re using what we learned to help educate and pass that message forward. We’re talking more now about how do we influence structures and systems, what trainings we need to mandate for staff, what we need to do with recruitment and retention and making sure voices of people we serve are at our decision-making table. We’re also still doing self-exploring,”

Consensus for Change

Girls Inc. executive director Roberta Wilhelm, who has done the REI work with her team, is impressed by the range of buy-in from Omaha stakeholders.

“There is a groundswell of support for these trainings and talk of how we build capacity for more of the same in our community to help us approach equity from a historical and factual context.”

Roberta Wilhelm is executive director of Girls Inc.

REI’s Hayes-Greene said, “We’re glad to see the cross-section interest” in places like Omaha’, and “even the naming of it, as we saw police chiefs, governors, mayors and news analysts use the term systemic racism. The movement is multi-racial and multi-generational.”

Wilhelm is intrigued by the potential such cross-fertilization may hold in Omaha, where DEI efforts abound, saying, “What would it look like if Omaha were on the front edge of anti-racism? What if we could help vaccinate folks with education, training, common language, common definitions?

What if it were a movement that involved the Chamber, education, arts and cultural institutions, non-profits, et cetera. What would herd immunity look like applied to racism? What would we have to do, to commit, to make real change?

“What if this sort of training was required for, say, all mentors? All board members? What if folks running for elected positions were asked,’’ Have you had REI training? What training have you received?’ What if it became expected that decision-makers should know this information?”

Where this city or nation goes with this work depends on the players and what they do with it.

“The movement doesn’t belong to just one nonprofit or one community group or one neighborhood,” Sherwood’s Tess Larson said. “It’s Omaha’s movement, Omaha’s initiative and Omaha’s momentum. It’s everyone’s morals, everyone’s character, everyone’s integrity, and frankly, everyone’s racism to address.”

Aligning Public Facing with Private Actions

Recently, Union for Contemporary Art founder and executive director Brigitte McQueen posted online a scathing personal essay that revealed the existence of an organization called Arts Omaha, which has since disbanded, whose all-white leadership represented major arts-cultural institutions. She said while many of these leaders and institutions supported DEI efforts on the surface, they behaved differently outside public view.

“Arts Omaha was essentially a secretive, segregated group of white directors that failed to act when they had an opportunity to diversify their membership by adding a Black director to their ranks,” she wrote, referring to her being denied a leadership post despite meeting the group’s criteria.

In her experience with Arts Omaha, she said, she became increasingly concerned by the dichotomy “to appear to support equity for BIPOCs (Black, Indigenous and People of Color) out of one side of their mouths, while they used the other side to keep us in our place.” She added, “These organizations are using the BIPOC members of their staffs and boards to shine a light on all the ways they’re working towards creating more equity in the arts, while moving in a much different way behind the scenes. We should be holding our cultural institutions accountable for their actions. We should not settle for lip service about equity when BIPOC arts administrators continue to struggle to work in an organizational culture of white supremacy.”

“We should not be okay with an organization that has historically failed to uplift BIPOC artists suddenly placing them front and center on every PR piece, without actually addressing the institution’s history of neglect and harm in dealing with those same artists. We should not simply listen to what they say while turning a blind eye to what they do. If we are going to fight for equity throughout the systems that negate it, we must fight for it fully. You cannot move to empower BIPOCs with one hand, while pushing them down with the other.”

Her expose elicited a flood of criticism directed at the institutions she named, quickly followed by statements from their executive directors that variously apologized, promised to do better and invited dialogue. All confirmed the

dissolution of Arts Omaha as they scrambled to distance themselves from it .

Micro Steps

“We’ve built a full-scale diversity-equity-inclusion strategy with a full portfolio of initiatives.

-Angela Cooper, Vice president and chief diversity officer at Mutual of Omaha

Outside the arts-culture sphere, and on a micro level, Mutual of Omaha feels it’s doing its part on the DEI front. “Mutual has a long-standing commitment to this work,” Cooper said. “We’ve built a full-scale diversity-equity-inclusion strategy with a full portfolio of initiatives. As part of that strategy we have multiple educational opportunities in place, including unconscious bias training, inclusion workshops and an allyship building program. That’s in addition to the education that happens in our employee resource groups. We really want to ensure we understand the unique experiences of our associates of color. That’s meant revitalizing our diversity and inclusion strategy around racial equity, and that’s where REI comes in.”

Like most workshop participants, Cooper found the REI content “offers a historical and contextual examination of structural racism most of us did not learn in school,” adding, “I think it helps to create a frame of reference for everyone to understand systemic problems and start thinking through systemic solutions.”

Her Mutual colleague Gail Graeve said, “I think the training is effective because it causes people to focus inward. It stays with you for a while.” She said a common response is, “how come I’m just hearing some of this for the first time?” REI co-founder Suzanne Plihcik confirms similar reactions along the lines of, ‘This is so eye-opening. I had no idea. I want my college tuition back.’”

Hayes-Greene with REI said the training draws on the notion that “an organized lie is more powerful and dangerous than a disorganized truth.” She added. “It’s not about what books you’ve read or what you know or what life experiences you have. It’s the way the information is put together that brings such clarity and answers so many questions.”

Revelations mean facing uncomfortable truths, said Graeve. Such thought-provoking material requires processing and direction. The training includes interactive breakout sessions. Emotions run high. Participants are advised to be gentle with themselves and not unload all at once what they’ve learned on their life partners. Intimate conversations about the themes and issues naturally ensue at home and in the office.

Said Cooper, “When you get all this knowledge in this learning experience it equips you to see things that might have been invisible to you before. What we do at Mutual is draw on this context to say how can we better notice inequitable systems, processes and parts of our culture where we need to make change. How can we be more curious, ask more questions and think about what we do differently in advocating for change.”

The experience, Cooper said, “has really equipped us individually to do that better and to build a shared ownership and expectation that everyone be doing that.”

“As organizations we certainly have the opportunity and the responsibility to facilitate that change,” Graeve said, “but it doesn’t work unless the people within feel that motivation, that inspiration and, frankly, the need to change. Omaha’s in our brand, it’s who we are, and our company can only be as strong as the community where we’re based. And our community can only be as strong as our most vulnerable friends and neighbors. Our foundation’s focus is on poverty. We know people live in poverty disproportionately by race. What REI is helping us do is think about the groundwater (source). Unless you’re able to really resolve and look past system change, we’re going to be stuck in the same place.”

As far as Mutual and its partners are concerned, Cooper said, “This is clearly the right thing to do and clearly the time to do it.” What comes next is up to participants. Sherwood is poised to be a catalyst and liaison for turning intention into action.

“Convening and community organizing is the real work,” said Larson. “REI provides the building blocks community groups can leverage for organizing. There have been many conversations about potential convenings. A number of organizations have expressed interest in creating a platform for this kind of community organizing and planning. Those conversations are still in the planning stages, but I am looking forward to seeing the true system work happen now.”

Implicit in all this is the reality that the more progressive a city becomes in this space, the more attractive it is to businesses and employees.

“Omaha and Nebraska need to compete in a competitive marketplace and we can’t do that effectively if we don’t have a really strong diverse and inclusive community” Graeve said. “I think it’s important all of us can and should be part of the change. REI really drives motivation to be better and to do better. That’s why we’re such proponents of it. It really does apply to anyone.”

Going the Distance

In any movement the energy around it eventually wanes as fatigue sets in. Activity then lags and participants fall away. But Hayes-Greene feels “there’s something behind this movement that isn’t going anywhere” having to do with growing sentiment that things need to be made right. “There’s a responsibility there.”

Cooper believes there’s built-in staying power to the extent participants are intentional in keeping it vital. “We’re well connected to other organizations in the community doing this DEI work or wanting to get started on this journey and inquiring about how to do it, how to build a strategy, how to start an employee resource group. I meet with multiple people a month in the community sharing what we’ve learned. It’s so important for us to talk about sustainability of this work. This is a journey. We need to get as much input as we can and we’re constantly looking at our strategy.”

Organic change, Cooper said, is key. “It can’t be something separate you’re doing off on the side. It must be integrated within an organization’s business strategy.” Mutual, she said, dedicates “regular, consistent communications about the importance of this work with our associates and the community,” adding that the company gauges “our effectiveness with metrics and performance expectations of our organization’s leaders.”

Robert Patterson of Kids Can is variously optimistic and pessimistic about America dismantling racism. “Sometimes I’m really hopeful, yes, this is possible, and then I’ll see something in the news and I wonder how are we ever going to get past this. I think eventually we will get there. Will it be in my lifetime? I don’t know. But I think we have to keep pressing on if we want anything to change.” OPD’s Michele Bang is under no allusions, saying, “There is going to be challenges in unwinding all of this.”

REI’s Plihcik reminds participants, “The power that has changed things throughout our history has come from the bottom, which is we try to get people to understand that building of a collective. Until they have sufficient power to challenge power,” she said, “that’s what the work is.”

“We do want for people to know this didn’t happen overnight and it won’t be resolved in the sort of grant cycle or program cycle agencies have,” said Hayes-Greene, who points out considerable resources have been thrown at symptoms of the problem without impacting its cause. “We have to think about this outside of old cultural standards,” she said. “What we hope to lay out for people is that as a nation we have not given this problem the time and attention it needs to understand what kind of problem it is. We keep misdiagnosing it. We need to commit to whatever it takes to understand that and do something different.”

For REI workshop inquiries, contact Tess Larson at Sherwood: TessL@SherwoodFoundation.org or (402) 341-1717.