Omaha’s Forgotten Panthers Part III: Fifty Years Behind Bars. Was it Justice? Or “One Monstrous Fraud?”

By Kietryn Zychal

History professor Tekla Johnson reflects on the North Omaha bombing and the arrests of Ed Poindexter and David Rice.

David Rice (Mondo) and Ed Poindexter were found guilty for the bombing murder of Omaha police officer Larry Minard on April 17, 1971. Shortly after the guilty verdicts were announced, they were escorted from the courtroom and taken to the Nebraska State Penitentiary in two separate cars to begin their journey as “lifers.” Mondo famously shouted to Ed as they got into their cars, “Do you want to drag?” His attorney told the Omaha World Herald, “David took the decision rather bravely.”

Mondo and Poindexter did not receive a sentence of “life without parole.” That sentence did not exist in Nebraska in 1971. According to official intake records, they were eligible for parole beginning in March 1972, which they were consistently denied.

Upon arrival at the prison, the two newest prisoners— 27767 and 27768— told the intake counselor they would be released within a year and that they had been framed because they were Black Panthers. Fifty years later in 2021, Mondo has been dead for five years and Poindexter, 76, recently applied to the Pardons Board for a commutation of his life sentence. By commuting his sentence to time served he may be released on parole due to his “exemplary career” while incarcerated and his numerous medical conditions including end-stage renal failure requiring dialysis six days a week. His prison doctors recommend that he receive a kidney transplant.

According to official intake records, Ed was eligible for parole initially in March 1972, but has been denied.

Mondo’s intake report stated, “He is quite creative in his writings and he has above average intelligence. An assignment in [the educational department] would seem beneficial to Rice and quite possibly to the institution.”

Artist credit: Emory Douglas

Poindexter’s intake report stateD, “By his own indication as well as his mother’s he seems to have a genuine concern for his fellow man.”

Artist credit: Emory Douglas

Looking back: what went wrong?

Frank Morrison spearheaded the building of the Great Platte River Road Archway Monument located east of Kearney, which is a tourist attraction highlighting the history of the Platte River.

In 1995, at the midpoint of their five decades of incarceration, after failed appeals and attempts to request commutation and parole, former governor and Poindexter’s public defender, Frank Morrison, 90, was determined to do two things before he died: build a “bridge” across Interstate 80 at Kearney as a monument to the pioneers who came through Nebraska, and get Ed Poindexter out of prison. He succeeded at the first and failed at the second.

In a 2003 video deposition Morrison, 98, stated, “There were a number of things that we [public defender’s office] didn’t have that were vitally necessary for a proper defense… There wasn’t an investigator at the time of the Poindexter trial… We didn’t have funds to make any scientific analysis [of the evidence]… Everything is relative, but I’ll say this: He [Poindexter] did not have an adequate defense.”

Ethel Landrum was chair of the Parole Board in the mid-1990s when it voted twice to recommend commuting Mondo’s sentence. She said Mondo and Poindexter’s case was treated differently from other murder convictions by the Pardons Board. “The length of time served for murder in Nebraska was less than 30 years,” she explained. Most prisoners who received a life sentence got a commutation and did not spend life in prison. “After reviewing Mondo’s record, we believed his sentence should have been commuted,” she said, “But because of the political climate at that time regarding police killings, Mondo and Ed were expected to die in prison.”

From Ed Poindexter’s perspective, his appeals and requests for commutation were denied because every step of the legal process, from the moment of his arrest, was “one monstrous fraud.”

THE FIFTY YEAR LEGAL ODYSSEY IN FIVE CHAPTERS:

A prisoner cannot appeal their conviction because they are innocent. A prisoner or their attorney must find legal violations in their original trial, or discover new evidence pointing to their innocence not available at the time of trial. Mondo and Ed claimed both, yet they were consistently denied new trials to prove it.

Early to mid-1970s

Direct appeals to the Nebraska Supreme Court were followed by federal appeals all the way to the United States Supreme Court focusing on Fourth Amendment violations in the search of Mondo’s house. (Poindexter was told he did not have standing to sue over the search of Mondo’s house, but his appellate attorney, Kenneth Tilsen of Minnesota, argued this ruling was wrong.) The SCOTUS decision, and its chilling effect on the future of habeas corpus and search and seizure claims, is explained in-depth in “Why the illegal search of Mondo’s home did not lead to a new trial.”

Late-1970s to 1980s

New evidence was found through discovery motions and Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests by Mondo’s new appellate attorney, Father William Cunningham, a Jesuit priest and law professor from California. Mondo— but not Ed— pursued relief in state and federal court based on several pieces of evidence not presented at trial, including:

A copy of the 911 call that Duane Peak confessed he made which did not sound like his voice. (The original tape was destroyed by Omaha Police in 1978 but a copy was found in 1980 in the belongings of the deceased supervisor of the 911 center.)

An FBI memo stating that the Omaha Police did not want the 911 call used at the trial because it would be “prejudicial” to their case against the defendants.

A letter allegedly written by Duane after the preliminary hearing in which he wrote that he had “no other choice but to say what he said,” and speculation that “other dudes” would have told a story that would have sent him “and the other dude” up.

State and federal courts dismissed the exculpatory value of the new evidence and denied Mondo a new trial.

Mid-1990s

Applications were filed with the Parole Board and Board of Pardons seeking release after exemplary prison careers. Twice, the Parole Board unanimously recommended** that Mondo’s sentence be commuted. (Poindexter, who transferred to the prison system of Minnesota to get a college education, bypassed the Parole Board and asked for a commutation hearing from the Pardons Board, which consists of the governor, attorney general and secretary of state.) Poindexter’s application was denied by the Pardons Board. Mondo received a hearing, but one of his attorneys, Lennox Hinds, walked out of the hearing after two hours in protest at the insincerity of the Board’s consideration of his client’s application.

**In 2016, the legislature passed a law which prevents the Parole Board from recommending a prisoner for commutation, unless the Pardons Board requests they do so.

2000 - 2016

Poindexter’s legal team, led by Robert Bartle in Lincoln, located Duane Peak, then nearing 50 years old, living under a new name, and received permission from the court to compare his voice to the voice on the 911 call. Voice analysis concluded that it was highly unlikely Peak made the original 911 call in 1970, yet the Nebraska Supreme Court and Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals denied Poindexter's petition for a new trial, dismissing his claims of prosecutorial misconduct and Peak’s apparent perjury. Mondo’s attorney, Timothy Ashford, filed similar appeals over the voice analysis which were also rejected.

In 2016, Mondo died from Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) in the prison infirmary shortly before his 69th birthday, after spending 46 years behind bars insisting he was innocent.

Emma Maasai and Athuman Juma released Mondo’s (David Rice’s) ashes in the winds of Uhuru Peak on Mt Kilimanjaro. Video by Charlotte and Pete O'Neal of their journey is available on YouTube. (bit.ly/3s0UQoQ)

2020

Poindexter, hoping not to die in prison like Mondo, filed an application to the Pardons Board, through his new attorney Timothy Ashford, to have his sentence commuted to time served so he may be released.

theorIes of the crime: what really happened?

The greatest conundrum after the convictions involved constructing a theory of what really happened. At trial, Duane Peak confessed that he delivered the suitcase and made the 911 call. If he was telling the truth— but Mondo and Ed did not make the bomb with him— who did? And, who made the 911 call?

Occum’s razor— the simplest explanation is the correct explanation— led observers and community members to believe Duane made the bomb with his relatives and implicated Mondo and Ed to save himself and his family. This rumor turned into legend over the years.

In 1982, Poindexter told Omaha videographer Ben Gray in a KETV documentary that Duane confessed that he made the bomb, but this is not borne out by the record of the case. In a 1991 British documentary, the narrator stated that Duane told police he made the bomb with his relatives but police “put pressure on him to implicate Rice and Poindexter” instead. This is also not borne out by the record of the case.

Attorneys David Herzog and Frank Morrison, and former police officer Marvin McClarty, each privately named other members of the NCCF whom they suspected of making the bomb or the 911 call. Suspicions never veered very far from Duane, his family, or other members of the NCCF.

Mondo eventually decided that he did not care who made the bomb. Why should an innocent prisoner have to figure out who really committed a crime he had nothing to do with? Poindexter, on the other hand, said he was tired of doing somebody else’s time. He would be happy for the real murderer to take his place but, like many others, his suspicions centered on Duane and his brother Donald. Both brothers accused him of being guilty, so he assumed they must be the true guilty parties. However, others were never convinced of Duane Peak’s guilt.

Ernie Chambers and others had doubts

According to the prosecution’s story, Duane put the bomb in the trunk before his sister drove miles through potholed streets in North Omaha to take him to 28th and Ohio.

In 1995 when I began my research, I interviewed Sen. Ernie Chambers and others about the case. Chambers was disgusted that anybody believed a 16-year-old kid was capable of carrying a heavy suitcase bomb with a clothespin triggering device all over North Omaha for six hours on a Sunday afternoon without causing an explosion.

He questioned Duane’s ability to get into three different vehicles and go for car rides with the bomb. On the last car ride, there were seven passengers in the car including his two nieces, an infant and a toddler. Inarguably, Chambers is the most influential intellectual voice in the Black community in Omaha, but on this topic, he was shouting into the waves.

The second person I interviewed who questioned Duane’s guilt was the late Frank Peak, his cousin and a leader in the NCCF. When I met him he asked with thinly veiled contempt, “How do you know Duane had anything to do with it at all?”

Duane’s sister Delia told me she never believed her brothers’ testimony. He had a suitcase and she did drive him to their old neighborhood with it. (The Peak siblings grew up in a house at 2809 Ohio.) She believed someone tricked her brother to deliver a suitcase to 28th and Ohio on August 16. She questioned, “Who was watching him? Who picked him out?”

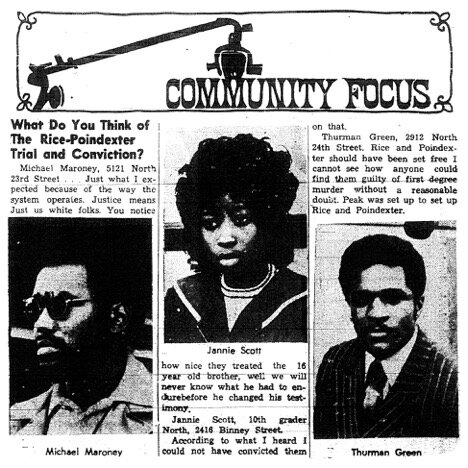

After the trial, a “Community Focus” column in a neighborhood newspaper asked residents for their opinions about the verdict. Thurman Green told the reporter, “Rice and Poindexter should have been set free. I cannot see how anyone could find them guilty of first-degree murder without a reasonable doubt. Peak was set up to set up Rice and Poindexter.”

Were Mondo and Poindexter framed by the FBI because of COINTELPRO?

The other red herring in the case involved figuring out what role the FBI and its counterintelligence program— COINTELPRO— played in the investigation and trial. OPD asked the FBI to analyze a tape recording of the 911 call. The FBI did not gather evidence at the bombing site nor did any FBI agent testify at the trial. ATF agents, however, participated in the illegal search of Mondo’s house, collected evidence at 2867 Ohio, transported dynamite samples and Poindexter’s clothing to the ATF lab in Washington, D.C., analyzed the evidence there, and four ATF agents testified at the trial. Yet, historically, the focus of many supporters has been primarily on the FBI instead of the ATF.

Examining an October 13, 1970 FBI memo regarding the 911 call— without bias— yields murky answers. The writer of the memo is Paul Young, the Special Agent in Charge (SAC) of the Omaha field office. Young left a paper trail of memos showing that he was capable of standing up to Hoover. For instance, he objected to “disrupting” the Black Panther breakfast program in Des Moines, telling Hoover that the Panthers were not extorting funds and that the program had community support. Young went so far as to write that any attempt to disrupt the breakfast would make the FBI look bad. He refused to do it.

Ed Poindexter, left, and David Rice, in the white sweater, leaving the courtroom after being convicted in the murder of Omaha police officer Larry Minard.

In the October 13 memo about the Omaha bombing, Young points a finger at the Assistant Chief of Police, Glenn Gates, and relays to Hoover that the Omaha Police have cancelled their request for the FBI to analyze the 911 call because OPD thinks it might be “prejudicial” to the murder trial against Peak, Poindexter and Rice. In fact, OPD doesn’t even want the FBI to keep a copy of the tape, they want it sent back.

One might argue this memo is a gift from Paul Young. Now we know the name of the guilty party who wants to suppress the 911 call from being used at the trial: GLENN GATES. Yet, most people who write about this memo infer that the FBI is suppressing the tape— when in fact, it is the other way around. OPD and the Douglas County Attorney are driving the bus on a murder trial in county court in Omaha. The FBI are passengers, at best. And when OPD told the FBI to get off the bus, they had no further involvement in the trial.

This memo shows the FBI knew that police believed the 911 call was exculpatory to the defendants. They had an obligation under “Brady v. Maryland” to also share the tape with the defense when they sent it back to OPD. And they failed in that constitutional obligation. The FBI shares blame that this crucial piece of evidence was never heard by the defense before the trial, or played for the jury.

If the tape had been played at the trial, it would have proved Duane Peak did not make the 911 call, and that he was committing perjury to claim that he did.

Every state or federal judge who dismissed this FBI memo as irrelevant to the fairness of the trial is responsible for keeping Mondo and Poindexter in prison.

That is where the real blame lies for this 50-year legal odyssey: with the courts.

In 1978, Lt. James Perry of the Omaha Police destroyed the original reel-to-reel recording that included the 911 calls made on August 17, 1970 stating in a deposition that he destroyed the tape because the trial, “was over as far as I was concerned.”

Perry was never punished for destroying the most crucial piece of evidence needed to identify the real killer of police officer Larry Minard— a recording of his voice.

The Courts They Were A-Changing

Nationally, it is well documented that court decisions beginning with “Stone v. Powell/Wolff v. Rice” in 1976 began “rationing scarce judicial resources.” Preventing so-called “frivolous” habeas petitions by prisoners was prioritized. Preserving “finality of convictions” became a goal of both courts and legislatures. The cumulative effect of these policies made it much more difficult for prisoners to appeal their convictions— or prove their innocence.

The gonzo journalist Dr. Hunter S. Thompson predicted this outcome when he wrote “Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail ’72.” He called Nixon’s new Supreme Court appointees Lewis Powell and William Rehnquist a “third-rate yoyo” and a “vengeful geek,” respectively. Thompson lamented that America’s courts were undergoing a “Nazi-bent shift.” He wrote, “The effects of this takeover are potentially so disastrous— in terms of personal freedom and police power— that there is no point even speculating on the fate of some poor, misguided geek who might want to take his “Illegal Search & Seizure” case all the way up to the top.”

One of the first poor misguided geeks was none other than David Rice in “Wolff v. Rice.”

It is no coincidence that the Innocence Project movement was born in the early 1990s during the era of rising mass incarceration which resulted, in part, from this narrowing of access to the courts.

One piece of legislation that particularly incensed Poindexter (and his attorney Bartle) was the Anti-Terrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996, or AEDPA, which was signed into law by President Bill Clinton. Passed after the 1995 truck bombing of the Murrah federal building in Oklahoma City that killed 168 people including 19 children, one of its provisions requires prisoners to ask permission before filing a successive habeas petition in federal court.

In 2010, Bartle asked a three-judge panel of the Eighth Circuit to file a habeas on the voice analysis of Duane Peak. They said no. He asked for a decision by all members of the court. They all said no. There is no appeal from their decision. Poindexter had now exhausted his legal appeals because AEDPA prevented him from having his day in court, as it was intended to do.

A free Mondo and Ed banner made by Ben Jones displayed on the Nebraska Capitol steps on March 13th, 2012. Photo taken by Mary Ellen Kennedy.

There is much, much more that could (and should) be written about the annals of the Rice/Poindexter case. After 50 years of being denied an opportunity to get back into court to prove his innocence, Poindexter now waits for the Pardons Board to put his application on one of their sporadically scheduled meeting agendas.

In recent Pardons Board meetings, all applications for commutation have been denied by the board without any hearing on their merits. Senator Bob Kerrey, also a former governor of Nebraska, wrote to current Governor Pete Ricketts in March 2021 encouraging him to commute Poindexter’s sentence for Easter because, after 50 years in prison, he has been punished enough. Ricketts called the letter “political.” Easter passed without a commutation.

“He has been punished enough ”

Bob Bartle recently wrote an article about the legal history of the Rice/Poindexter case for the Nebraska Bar Association magazine which will be published this summer. He speculated that the Pardons Board was unlikely to commute Poindexter’s sentence unless “a different conspirator behind the tragic death of Officer Minard” could be identified.

So, that’s the burden: the prisoner who pleads his innocence is expected to figure out who really committed the crime for which he has paid with his freedom, a crime which he claims he knows nothing about.

Is that justice? Or one monstrous fraud?

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Kietryn Zychal first wrote to Mondo (David Rice) in 1993 when she was 31 years old. At the time she was an actress. She began writing to Ed Poindexter and researching the Rice/Poindexter case around one year later with the goal of doing a performance piece about it or an eventual documentary. She and host Kathy Still produced a 1998 radio documentary about the case on KPFK in Los Angeles. Kietryn got her first job as a newspaper reporter in 2007 in Pennsylvania, having given up on her ambition to become a professional actress. The unsolved mystery of the Rice/Poindexter case nagged at her and she returned to Nebraska in 2012 to continue the research she began in the 1990s. At age 56, she earned a master's in journalism from Northwestern University. NOISE's series "The Forgotten Panthers" highlights the research Kietryn began 27 years ago.